On June 15th, 1904, congregants of the St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, including many former members who loved the annual outing and used it as an excuse to return to the old neighborhood of Kleindeutschland, “Little Germany,” gathered on the pier at the end of East 3rd Street. Families and children were tremendously excited to take to the water and enjoy the excursion to Locust Grove on the north shore of Long Island. What promised to be a magnificent day for all, one with beautiful weather and the promise of relaxation and keeping cool would soon turn into an absolute nightmare that would devastate the whole enclave.

The wreck of the General Slocum off of Hunts Point. The starboard paddlewheel and box somehow remained intact. Several survivors were found holding onto the wheel. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

For several years, the church had set up an annual outing for its congregants, who lived in crowded, cramped conditions in what is now the East Village. There was little opportunity for children to access fresh air and open spaces in the neighborhood, and so local organizations often organized excursions on steamships, many of which plied the waters in and around New York City, as these trips were seen as being beneficial for both mind and body. The day before the excursion was a flurry of preparations, as children were bathed, and their best outfits were laid out. This would be a day for the women and children of the congregation, as many fathers had to work and could not attend the festivities.

A crowd outside St. Mark’s Lutheran Evangelical Church. The church, built in 1847, still stands today. From History of the General Slocum Disaster by John Stewart Ogilvie.

The General Slocum was built at the Devine Burtis shipbuilders in Red Hook and launched in 1891. The wooden ship featured an engine built by the W.A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken. She was operated by the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company, which ran excursion ships that plied the New York waterways. In the early years, the General Slocum routinely operated from Manhattan to the Rockaways, running two times a day on the weekends. Later, she would operate up and down the Hudson River. However, the ship had been plagued by mishaps early on, including running around several times, being involved in numerous collisions, and a series of mechanical failures.

The General Slocum loaded with passengers. She could hold up to 2,500. It is estimated that just over 1,300 people were aboard for the excursion to Locust Grove. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

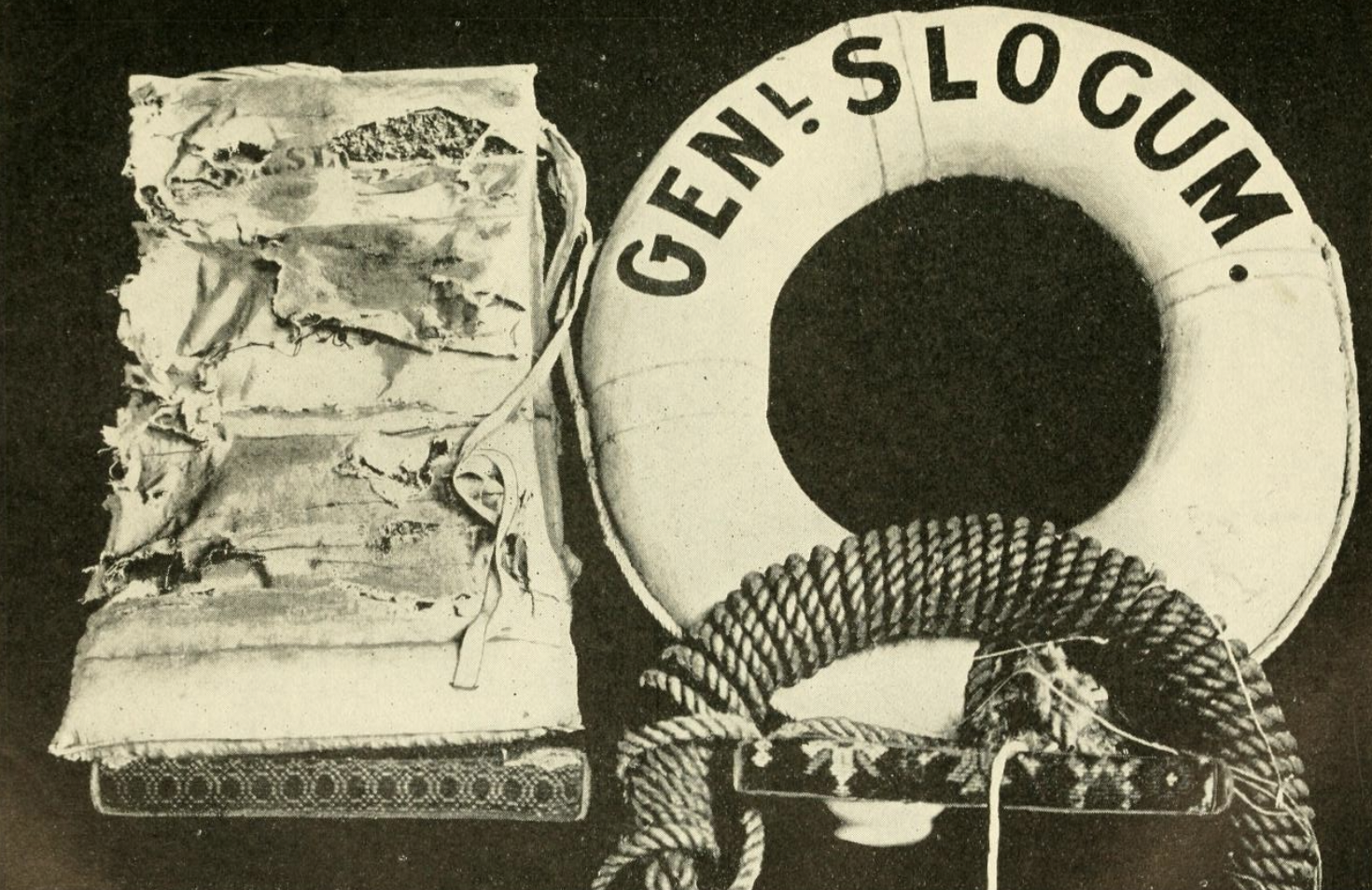

Within just a few years the once proud ship was considered old and outdated, although the company dismissed this, and continued to paint the ship bright white in anticipation of the upcoming season. A ship inspection the previous month had largely been conducted by a novice inspector, who marked the dusty Kahnweiler’s Never-Sink Life Preservers, stenciled with a faded “passed inspection” mark from 1891, as safe; opened the standpipe valves but didn’t check that water flowed through them; failed to check that the hoses were operational; marked the lifeboats as able to swing under the davits (although the annual paint jobs had effectively cemented them to the deck, and parts were tied down with wire); and neglected to examine the forward rooms, which were stuffed with flammable objects, including oil drums that were leaking into hay and canvas strips that carpeted the deck. The old wooden ship passed the meager inspection and was cleared to run for the 1904 season.

Rotten life jackets found after the disaster, stamped with Passed U.S. Ass’t Inspection, June 18, 1891. The life jackets were virtually useless and contributed to the death toll. From Denkschrift der General Slocum Katastrophe, published by W.W. Wilson, 1904.

A cartoon published by The Brooklyn Eagle the day after the disaster.

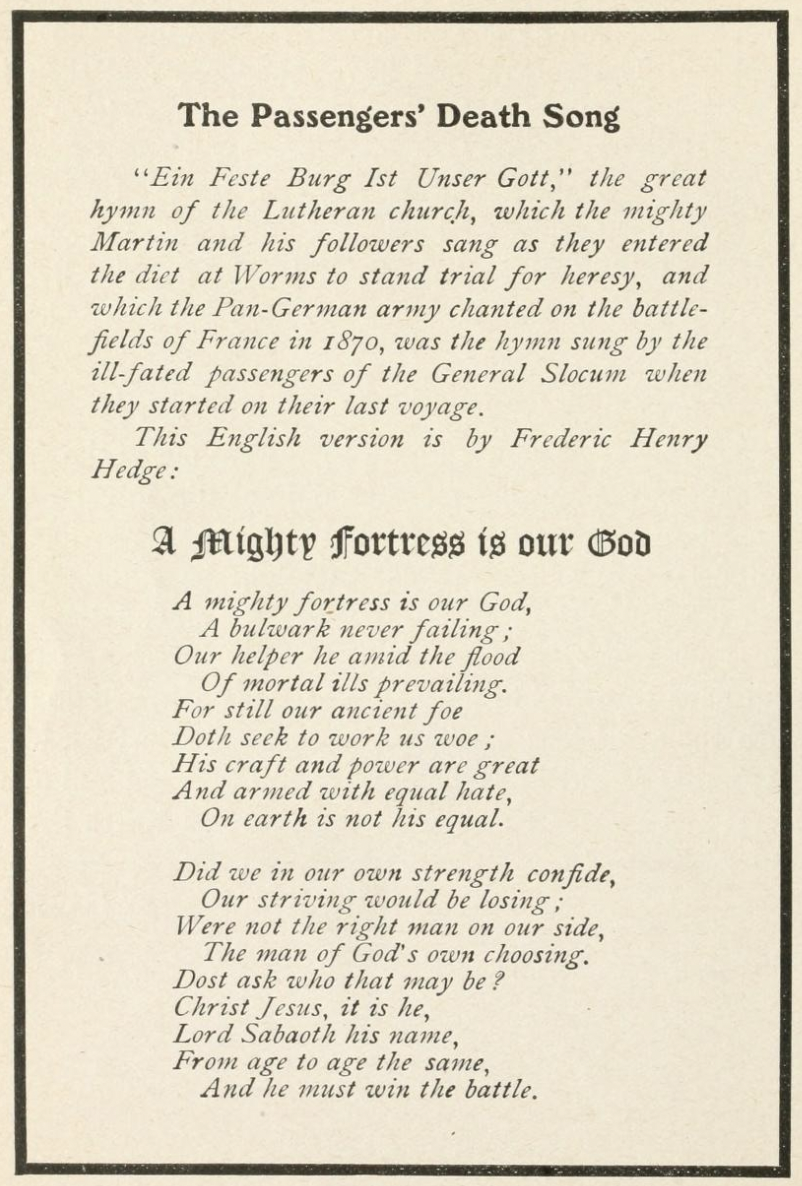

Just after 8 AM, the General Slocum approached the East 3rd Street pier, which was already crowded with folks eager to get onto the old ship and secure the best seats. A local band hired for the occasion played popular German hymns and songs, including “Ein Feste Burg ist Unser Gott” (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God). Boarding began around 8:30, and despite a dedicated departure time of 8:45, congregants begged Reverend Haas to hold the ship so that their friends and relatives could make it. About an hour later, the ship finally set sail, although just before it left one woman who had a terrible premonition about an impending disaster managed to gather her children and leave the ship, followed by another man who was spooked by what she said to him. It was a decision that saved their lives.

The General Slocum as she looked when fully loaded with passengers. From The New York Tribune, June 16, 1904.

The English Translation of Ein Feste Burg ist Unser Gott, which the congregation sang as they set off, along with other hymns and German songs. From New York’s Awful Excursion Boat Horror, edited by John Wesley Hanson.

Spirits were high as the ship steamed up the East River at an estimated speed of 15 knots, and the promise of a beautiful day away from the teeming city was exhilarating for those on board. Ferries, pleasure crafts, and other excursion boats were plying the waters, and the children on the top decks waved to them and cheered the horns as Pastor Haas went around the upper decks talking to congregants. As the ship passed Blackwell’s Island (Roosevelt Island) none of the merrymakers were aware that they were already in grave peril.

Boats on the East River, seen from Manhattan, 1903. In the middle is the lighthouse at the northern end of Blackwell’s Island (which still stands). To the left is Hallet’s Point in Queens. From New Harlem Past and Present by Carl Horton Pierce.

Just before 10 AM a fire broke out below decks. People onshore noticed smoke coming from the steamer as it continued up the East River and waved to try and alert those on the boat. Other boats saw the smoke as well and issued shrill warnings with their whistles. It appeared that no one on board was aware of what was happening, as the band was enthusiastically playing on and people were going to the refreshment stand for ice cream or beer, and milling around the top decks. An inexperienced deckhand was alerted to the situation by a young boy and rushed down to find smoke billowing from the lamp room. He opened the door and tried to extinguish the flames but, failing to do so, decided to alert the ship’s first mate. No fire drills had been carried out on the boat, and the deckhand neglected to close the door, adding oxygenated fuel to the growing fire.

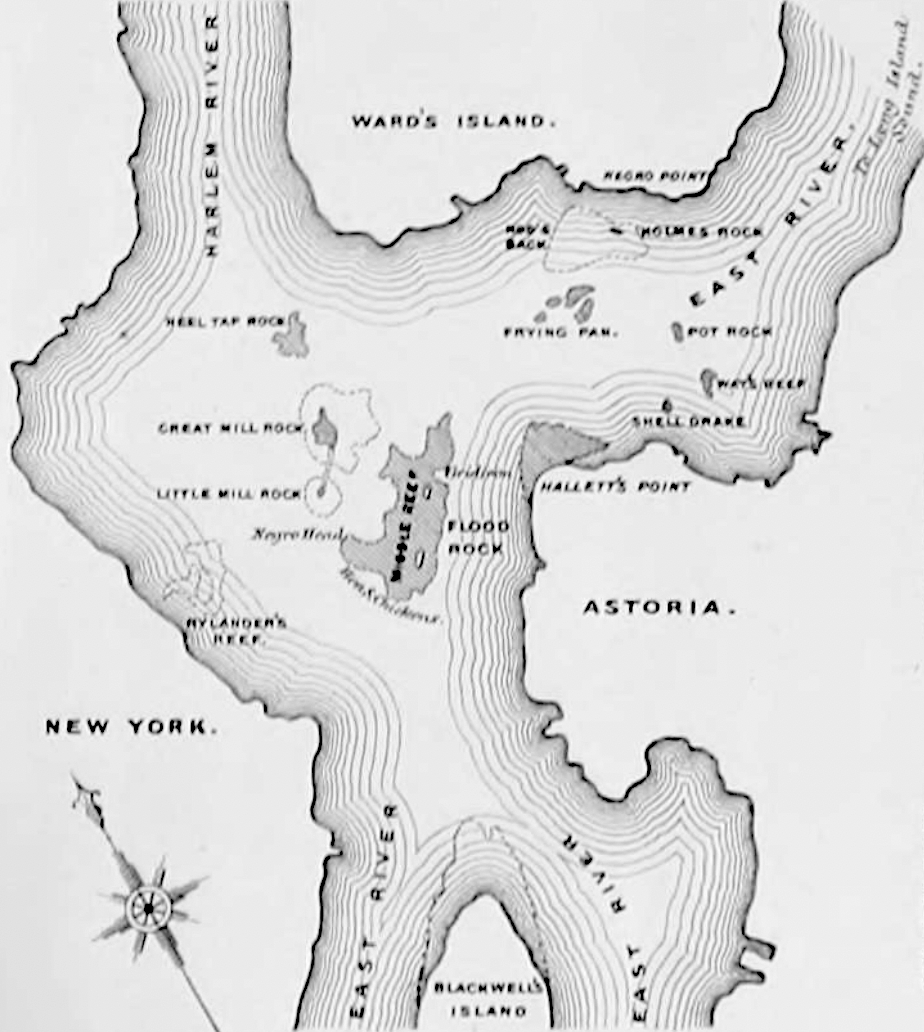

Hell Gate reefs as they appeared in the 1880s. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had blasted numerous reefs, shoals, and rocks in the area to improve navigation, but this was still one of the most hazardous areas to bring a ship through. Note Great and Little Mill Rock on the left, which served as the base to organize operations and conduct surveys. Over the years the two islands were connected and expanded by the debris from the blasts that removed the other impediments in the channel. From Blasting Operations at Hell Gate by Leveson Francis Vernon-Harcourt, 1886.

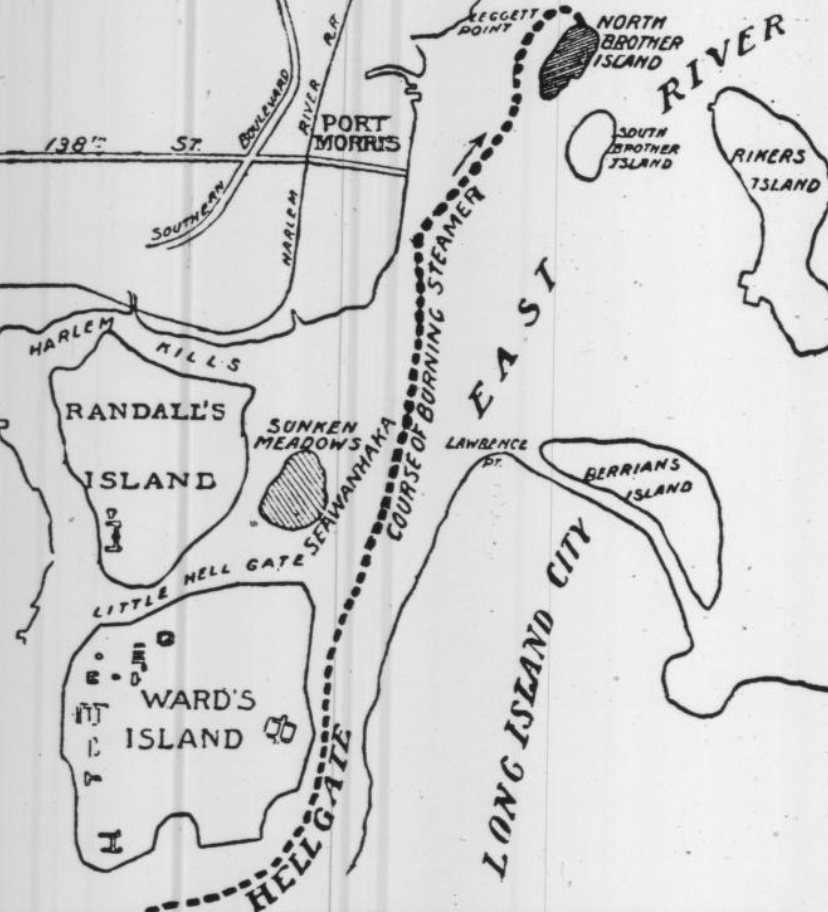

By the time the boat was passing Hallet’s Point, Captain William Van Schaick was focusing on navigating the treacherous waters of Hell’s Gate. However, his attention was broken by a boy yelling up to him that the boat was on fire. Annoyed, van Schaick dismissed the boy. It would be up to the other crew members to try and address the situation first. Edward Flanagan, the first mate, called up to the pilot house to warn the Captain that the ship was aflame, and then unfurled the fire hose and turned on the pipe. This hose, which had passed inspection a month before, was so useless that it tore in several places and was blown off of the standpipe. A rubber hose was procured but could not be attached to the pipe, and the efforts to fight the fire ended there, as the fire was rapidly progressing up the decks. This caught the Captain’s attention, and he made the fateful decision to beach the boat on North Brother Island.

A map showing the course of the General Slocum when she was still burning. The decision to beach the ship on North Brother Island was heavily scrutinized for costing precious time and leading to a greater loss of life. From Harper’s Weekly, June 25, 1904, Vol 48, No 2479.

Word of the fire passed quickly among the passengers, although some dismissed it as steam from the refreshment stand. Others saw the smoke coming up through the stairwells and moved to other parts of the ship. Pastor Haas had noticed the smoke and moved his wife and daughter, but tried to keep his congregants calm. This effort was compromised as people yelled out “Fire!” and folks started to panic. Attempts to pry the lifeboats loose were in vain, as they were tied down and painted over, preventing them from being launched. Crew members were nowhere to be found.

A lifejacket and life preserver salvaged from the wreck. Both were found to take on water and sink. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

Wrenching the lifejackets from the ceiling, people fought over them and clawed them away, ripping them in the process and sending cork dust into the air. Mothers strapped their children into the jackets and threw them into the water, but the disintegrating cork took on water and pulled them beneath the surface. Although many passengers braved the churning water, others were too afraid, and huddled together in the face of the flames, which swiftly claimed their lives. For those who could swim, they were still weighed down by heavy dresses and woolen clothes, and depending on when they leapt off the vessel could be at risk of others jumping on their heads. Those who were drowning, frantic and thrashing around, got ahold of others and pulled them down with them. It was absolute chaos.

An artist’s depiction of the General Slocum on fire. It notably shows people in the process of trying to rescue those who are drowning, and in the background are tugboats that followed the wreck, rescuing people and picking up bodies. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

Panicked passengers jumping from the upper decks of the boat. From History of the General Slocum Disaster by John Stewart Ogilvie.

It only took minutes from the Captain’s decision to drive the General Slocum aground until it did so off of North Brother Island, with the ship still ablaze. Many boats were alerted to the disaster and followed the ship, picking up the few survivors they could find and collecting bodies. Multiple alarms had also gone out from witnesses on land, who were watching the horrific scene unfurl before them. Fireboats from the Bronx worked to put the General Slocum out, although the heat from the inferno was so intense that it melted parts of the fireboats and other rescue craft. The decks of the General Slocum, weakened by fire, had fallen on top of each other, crushing those who were somehow still clinging to parts of the deck or railings. It was towed away from the island to prevent the fire from spreading ashore, and came to rest off of Hunts Point.

The blazing wreck after it has been run aground. The tangled metal mass would sink further into the water as the tide started to go out. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

Fireboats attempting to put out the fire on the General Slocum. From Leslie’s Weekly, June 23, 1904, Vol 98, No 2546.

The sunken ship after the fire had been extinguished. Divers were dispatched to comb the wreckage, and found many bodies trapped when the decks collapsed. From Harper’s Weekly June 25, 1904, Vol 48, No 2479.

North Brother Island was home to a quarantine hospital (it would later be home to the infamous Typhoid Mary), and doctors, nurses, other staff members, and even patients rushed to help with the rescue efforts. People commandeered whatever water-going vessels they could to get to the island and assist, from policemen and firemen in Harlem, to railroad and dock workers in the Bronx, to the captain of a dredge from Astoria. Several survivors of the disaster risked their lives by going back into the water to save others, and many unknown heroes served to help others, some of whom paid the ultimate price for doing so.

A view of some of those rescued from the water, along with their rescuers, many of whom worked on North Brother Island. From Denkschrift der General Slocum Katastrophe, published by W.W. Wilson, 1904.

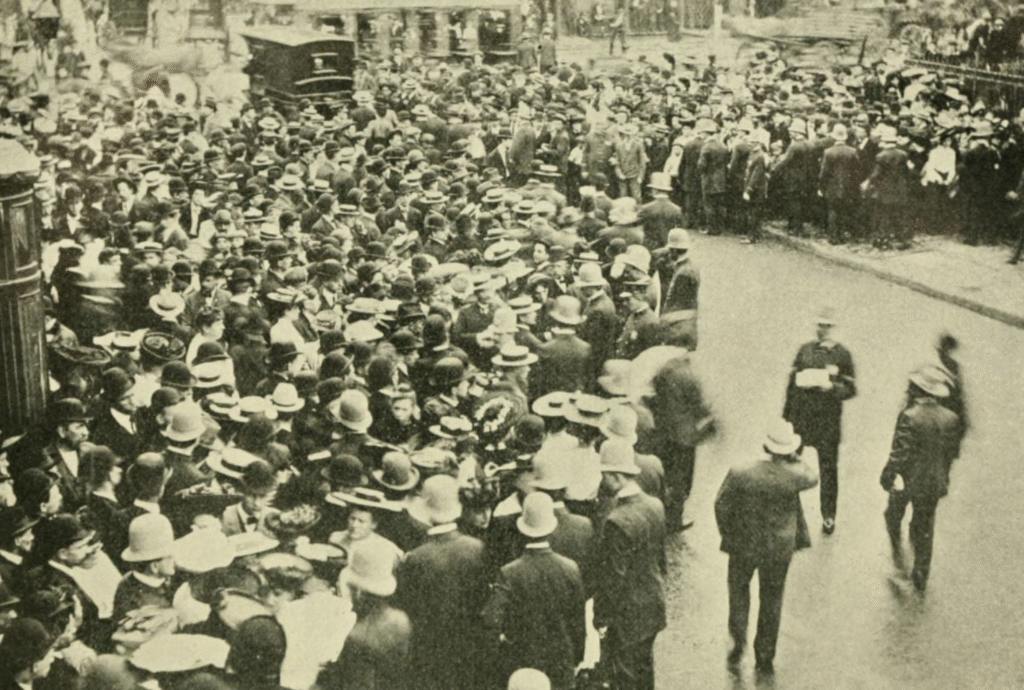

An anxious crowd on the Manhattan shore gathering to hear news from first responders. From Leslie’s Weekly, June 23, 1904, Vol 98, No 2546.

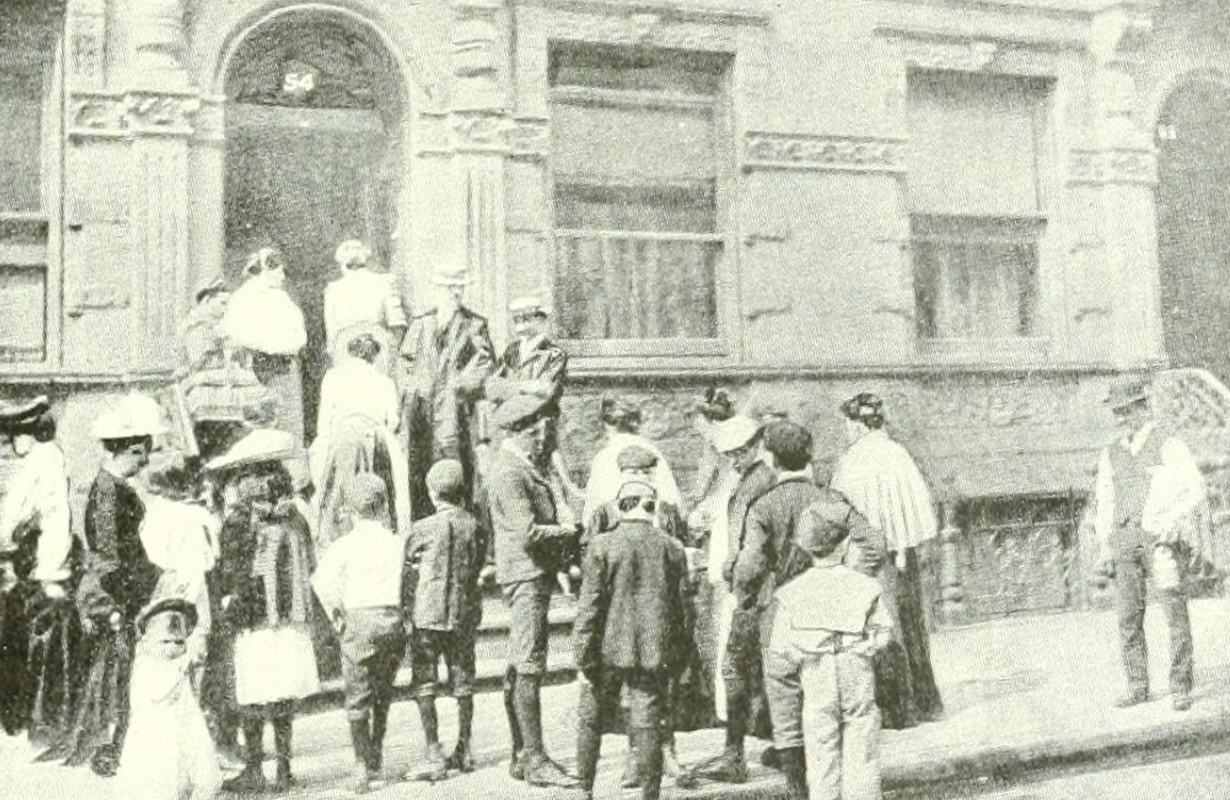

In Kleindeutschland, people gathered outside of St. Mark’s Church to hear news about their relatives and loved ones. Bulletins were posted showing the names of the dead and injured. From Denkschrift der General Slocum Katastrophe, published by W.W. Wilson, 1904.

1,021 people died in what was the worst disaster the city had ever seen. Bodies washed up on the shores of North Brother Island for many days, and others were found as far away as the Lower East Side, close to where they had lived. The bodies were brought to a temporary morgue on 26th Street (where the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire would also be taken), and family members and mourners filed past the coffins to identify their loved ones.

(Top) Rescuers lined up on North Brother Island to collect the bodies that washed ashore as the tide went out. (Bottom) Combing the wreckage for bodies, some of which were wedged in the paddle wheel. From The New York Tribune, June 16, 1904.

A boat bringing survivors of the wreck to Manhattan. Recovered bodies were also aboard, and were taken down to the temporary morgue set up on 26th Street. From New York’s Awful Excursion Boat Horror, edited by John Wesley Hanson.

Scenes inside (top two, looking east and west, respectively) and outside the temporary morgue set up on 26th Street at the pier operated by the Department of Charities and Corrections. At one point there were so many bodies in the morgue that there were no coffins left. From Annual Report of the Department of Public Charities of The City of New York for 1904.

The crowd outside the morgue. People lined up outside for hours to file by the coffins, attempting to identify their loved ones by their clothing, hair, jewelry, or other valuables. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

Few residents of Kleindeutschland were untouched, with most losing family members or friends. In some cases, whole families died together. The neighborhood was decked out in black crepe and flowers. In some cases, whole families died together, and it was not unusual to have several victims in one household. Pastor Haas lost both his wife and daughter in the tragedy. Funerals soon began and continued each day throughout the month, with many processions making their way across the Williamsburg Bridge to the Lutheran Cemetery in Queens. A monument to the 61 unidentified dead was erected there in 1905.

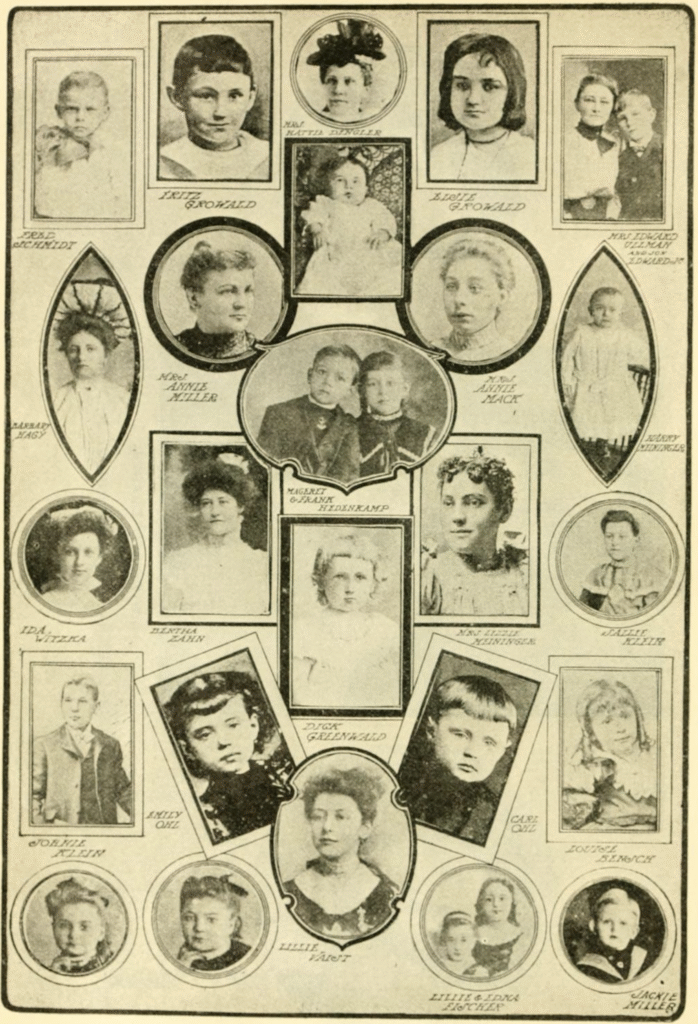

Some of the victims of the disaster. Most of those who perished were women and children. From New York’s Awful Steamboat Horror by H.D. Northrop.

A doorway covered in mourning flowers. Five family members died in this house, and only the father, who had to work, survived. From New York’s Awful Excursion Boat Horror, edited by John Wesley Hanson.

(Top) Mourners outside a building that had victims in every apartment, fourteen families in total. (Bottom) Mourners lined up for funerals at the Lutheran cemetery in Queens. From Denkschrift der General Slocum Katastrophe, published by W.W. Wilson, 1904.

Funeral of 29 unknown victims, paid for by the city. From New York’s Awful Excursion Boat Horror, edited by John Wesley Hanson.

Following an inquisition into the wreck, Captain Van Schaick was sentenced to ten years, spending part of his sentence at Sing Sing before being pardoned by President William Howard Taft. No charges were brought against the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company or its leadership.