The loft building in which the fire started was touted as “fireproof,” but within the floors occupied by the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, rows of tables with sewing machines were tightly packed and laden with piles of clothing. To make sure that the workers weren’t stealing anything, the owners had ordered that the exit doors be locked until their shifts were over. The floors, window frames, and tables were made of wood, and wooden partitions were in place in front of the elevators, with doors that opened inwards. There was no automatic sprinkler system in place, and fire drills were never conducted. As the workers sewed their garments, cuttings and scraps were brushed onto the floor or piled into heaping baskets. Oil from the sewing machines dripped down into the rags below. Smoking was commonplace, and although it was technically not allowed, plenty of people did it anyway (including the owners and foremen). A few minutes after 4:30 PM on March 25th, 1911, someone on the 8th floor flicked a lit match or cigarette onto a bin of scraps, which quickly caught fire.

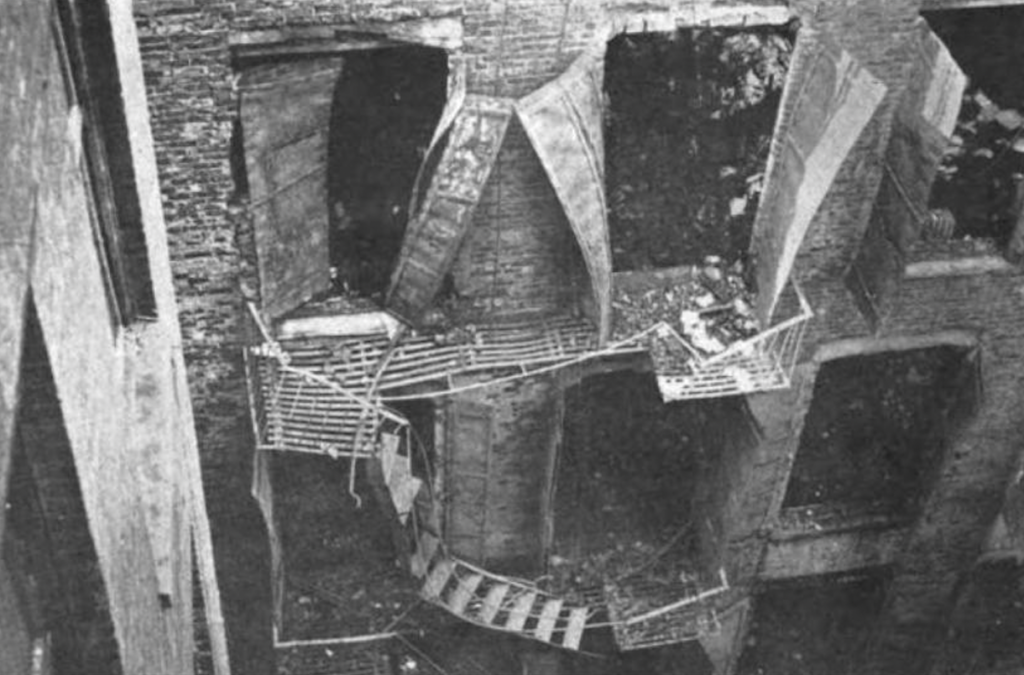

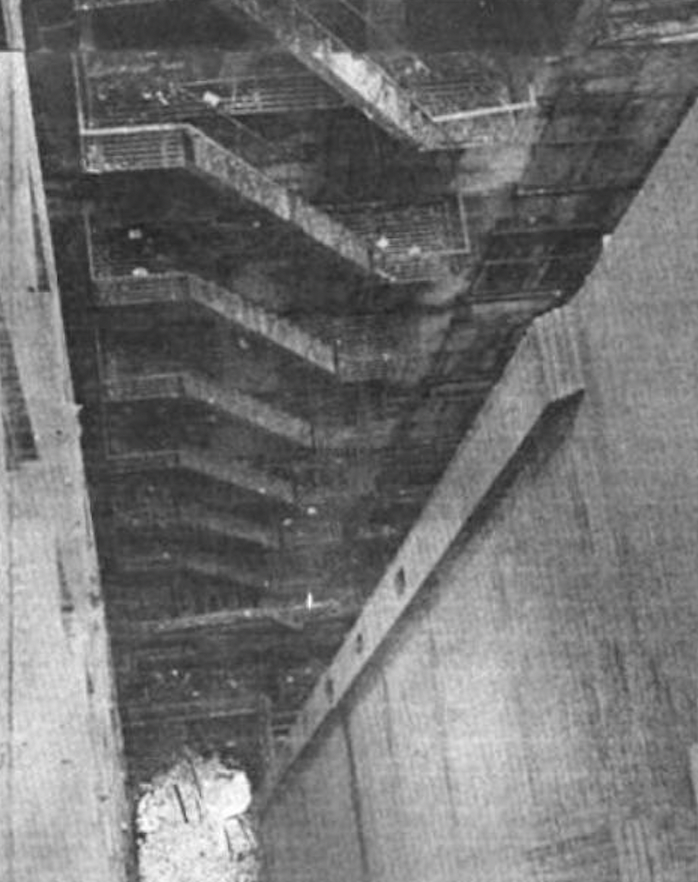

The Washington Place side on the 9th floor after the fire. On the left are the two small elevators, which ran until they broke down under the weight from people jumping atop them. To the right is the staircase, which was inaccessible since the door to it was locked. From Loss of life through carelessness and panic: Being a report on the Asch Building fire, by F.T.J. Stewart, 1911.

Firefighters directing hoses onto the Asch Building. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company occupied the top three floors of the building, which were out of reach of the hoses. From McClure’s Magazine, September 1911, Volume 37, Issue 5.

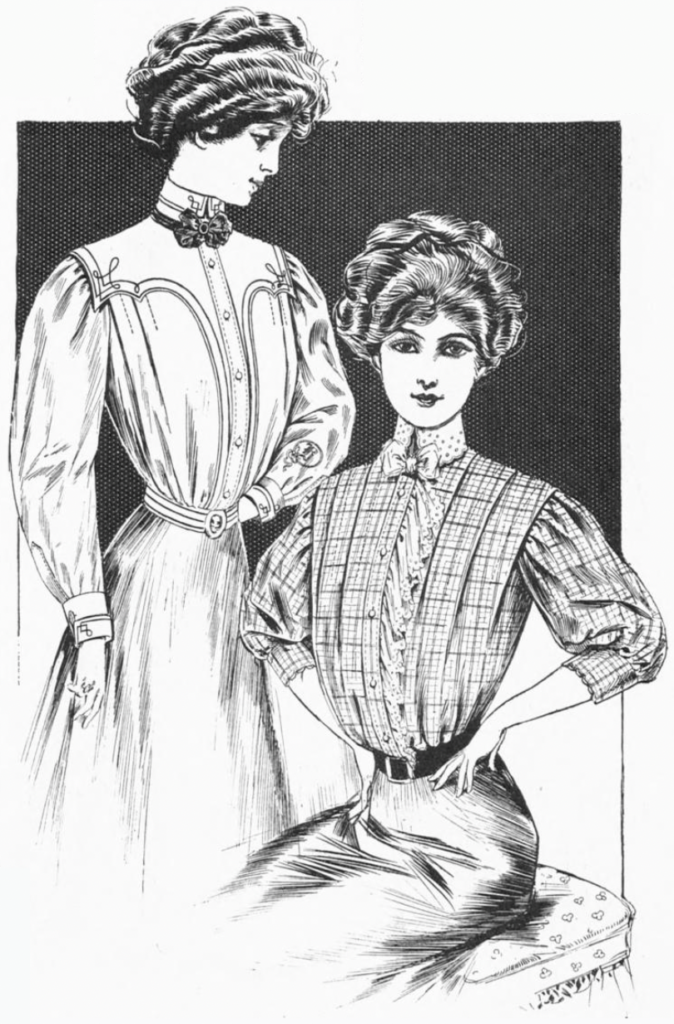

Those who worked in the garment industry, manufacturing mass-produced clothing items such as shirtwaists, a type of women’s blouse that was paired with a skirt, often worked six days a week, for up to 14 hours in a shift. Some workers were made to buy their own thread, needles, or irons. While men in the garment industry could earn around $10 a week, women only earned around $6 a week, and in some cases the younger girls were paid as little as $3 a week. If they worked more hours, which they were often forced to do by management, they were not paid overtime; they might occasionally receive a piece of apple pie instead, but that was it. The workers were closely monitored to ensure that they weren’t talking or taking too long in the bathroom, for which they could be fined. Many of the workers were under 20 years old, and a majority of them were Italian or Jewish immigrants who lived in tenements.

An advertisement for shirtwaists. They were a highly popular, versatile garment worn by women from all social classes. From The Delineator, April 1908.

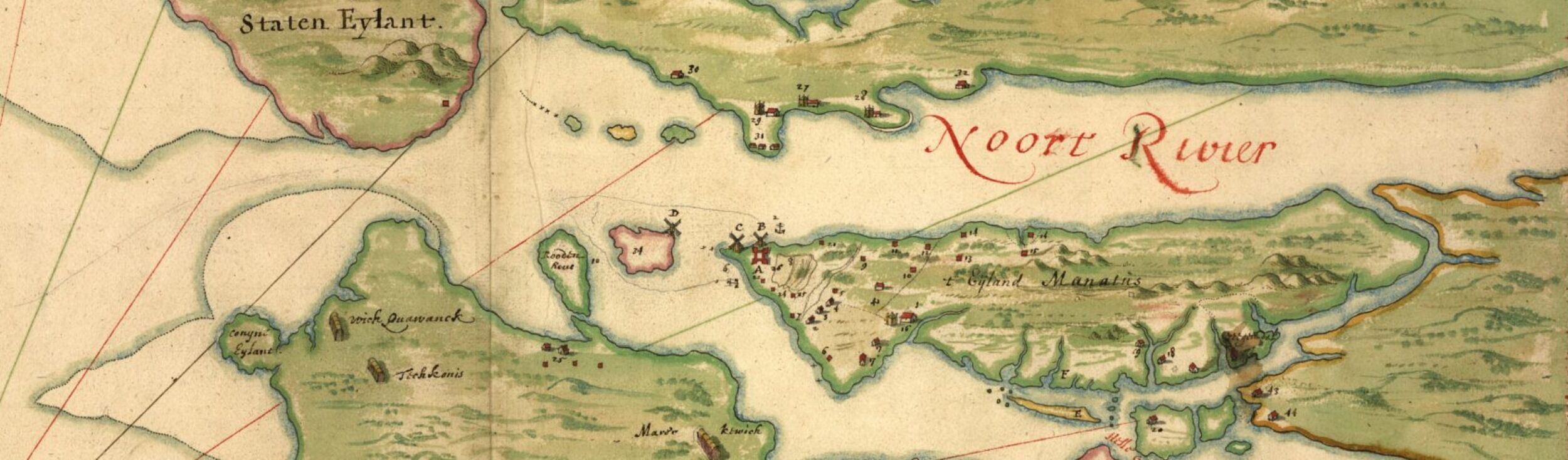

A typical clothing factory in a loft building, similar to the Asch Building, where the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was located. The company was housed on the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors. From Hampton’s Magazine, June 1911, Volume 26, Number 6.

Working conditions were so dismal that the workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company had gone on strike in 1909 along with workers from Leiserson’s, another large garment company. Their picket lines were broken by prostitutes, hired by owner Max Blanck, who fought with the strikers, and hired thugs to beat them up. If they complained, the police would arrest them. Steadfast and supported by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), the workers debated the merits of a general strike at Cooper Union that November. They were bolstered by the zeal of activist Clara Lemlich, a founder of Local 25 who took charge of the meeting and called for the strike, which thousands supported.

Strikers selling copies of a special edition of The New York Call newspaper. The proceeds benefited the strikers. From Munsey’s Magazine, April 1910, Volume 43, Number 1.

What became the “Uprising of 20,000,” also known as the shirtwaist strike, saw thousands of workers, a majority of which were women, on strike in New York; a similar strike was later held in Philadelphia. Demands included a wage increase, overtime pay, a 52-hour workweek, and an end to punitive fines. Numerous smaller companies agreed to these terms. However, larger companies like the Triangle Shirtwaist Company refused to negotiate or recognize the union. Additional demands for doors to the stairwells to be unlocked and better fire escapes to be constructed had been completely ignored by Blanck and his business partner Isaac Harris. Once the strike ended, those who worked for the Triangle Shirtwaist Company were not much better off.

Strikers picketing outside a garment factory on the Lower East Side. From Munsey’s Magazine, April 1910, Volume 43, Number 1.

At the Asch Building, where the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was located, the blaze spread quickly across the 8th floor, fed by the oil that had seeped into the rags. Several attempts to douse it with water were unsuccessful. The flames leapt up, reaching pieces of fabric and patterns that were hung overhead and reaching other containers filled with cuttings. Workers on the 8th floor were largely able to escape using the narrow interior stairs or using the one fire escape, while those on the 10th floor went onto the roof and escaped via ladder with the help of some law students from NYU who offered their assistance. However, the fire spread so quickly that those on the 9th floor were largely trapped.

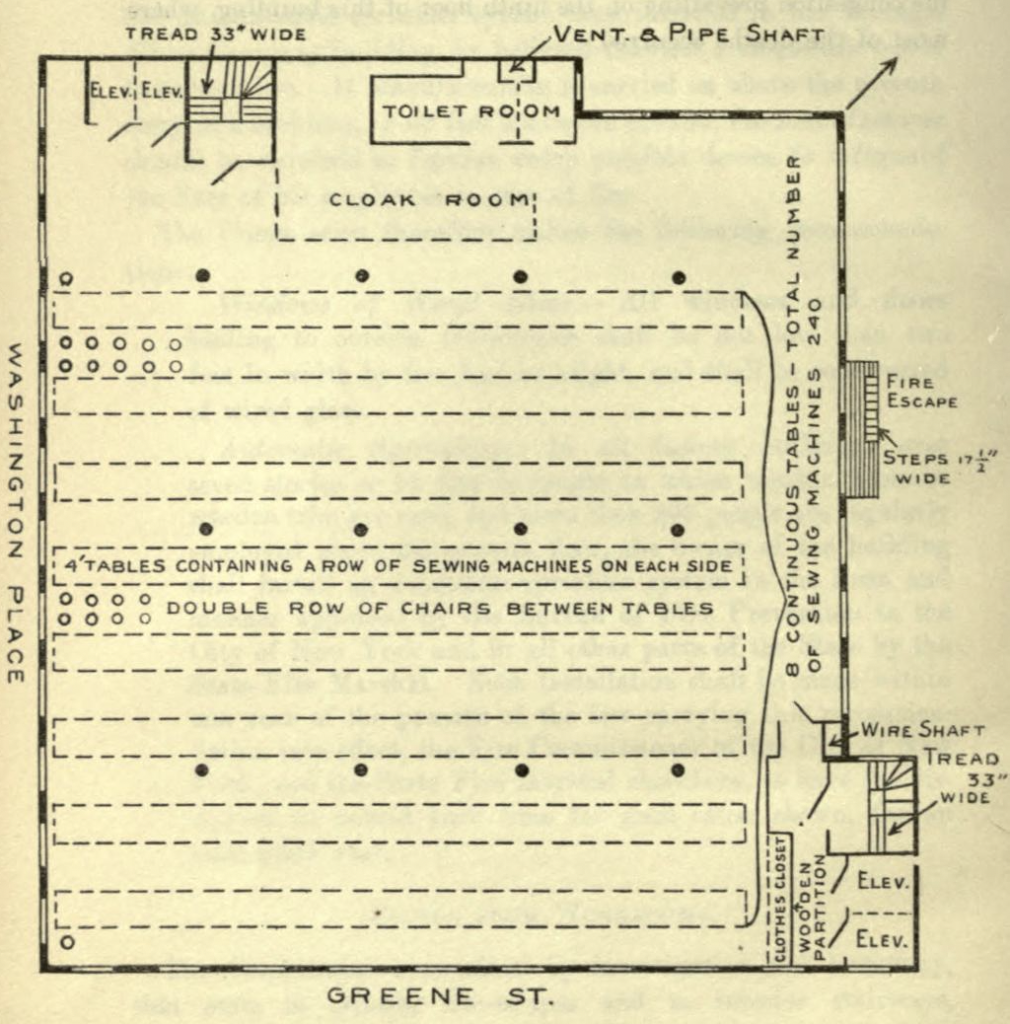

The plan of the 9th floor, showing where the rows of tables were located and their relation to the stairways, elevators, and dressing room. From the Preliminary report of the Factory Investigating Commission, 1912.

When the 9th floor foreman heard the fire alarm, he fled, taking the door key with him. Some workers managed to escape by squeezing onto one of the tiny elevators when it was still able to run. People were so desperate to escape the flames that they jumped into the shafts, and although the elevator operators continued to operate them as long as they could, the elevators broke down. Other workers piled onto the flimsy inner fire escape, which had previously been used by workers from the 8th floor. However, it quickly buckled under the weight, sending them plummeting to their deaths.

The sole fire escape, which opened to a closed space and ended at the second floor. Some of the workers who escaped from the 8th floor using the fire escape had to fight through metal screens to make it inside. From Hampton’s Magazine, June 1911, Volume 26, Number 6.

Those who were left were engulfed in an inferno. The fire ladders couldn’t reach past the 6th floor, and the life nets used by firemen were rendered useless, torn to shreds by falling bodies. Onlookers watched in horror as workers appeared at the windows with their clothes and hair on fire and began to jump. Some were pushed out, crowded by the panicked, screaming people behind them. Others jumped together, holding hands. Their bodies hit the pavement with an awful thud or crashed through the glass vaults into the basement.

A hole in one of the glass vaults, which a falling body had caused. It was not uncommon to see basement vaults extended under the sidewalk, with thick glass skylights embedded in them (this technique was used in early subway stations). From McClure’s Magazine, September 1911, Volume 37, Issue 5.

Crumpled bodies lay in bunches on the street. There were so many that the fire engines and rescuers had trouble maneuvering, and the horses reeled at the smell of blood. Many other workers remained on the 9th floor. They were burned beyond recognition and piled together against the locked doors, near the windows, or in the dressing room. Word about the fire had gotten out, and families and friends of the workers arrived at the horrific scene. In the two hours after the fire, it would grow to an estimated 20,000, who watched as firemen carried bodies into waiting ambulances or wagons to take to the morgue.

Hurrying a survivor to an ambulance (above). Responders carrying a coffin for transportation to the morgue on 26th Street (below). From Harper’s Weekly, April 1, 1911, Volume 55, Issue 2832.

The flames on the 8th floor were extinguished less than 30 minutes after the first person had discovered the blaze and cried out “fire!” to warn others. The firefighters made their way up and systematically fought the flames on the 9th and 10th floors. With everything under control after 6 PM, they turned to the grim task of recovering the bodies in the building. They worked until midnight hoisting the bodies out of the windows and lowering them down, while officers on the ground examined and tagged the dead. At one point, they ran out of coffins, and made temporary ones, before switching to ones returned from the morgue. The scene was so overwhelming that the first responders switched shifts three times throughout the night.

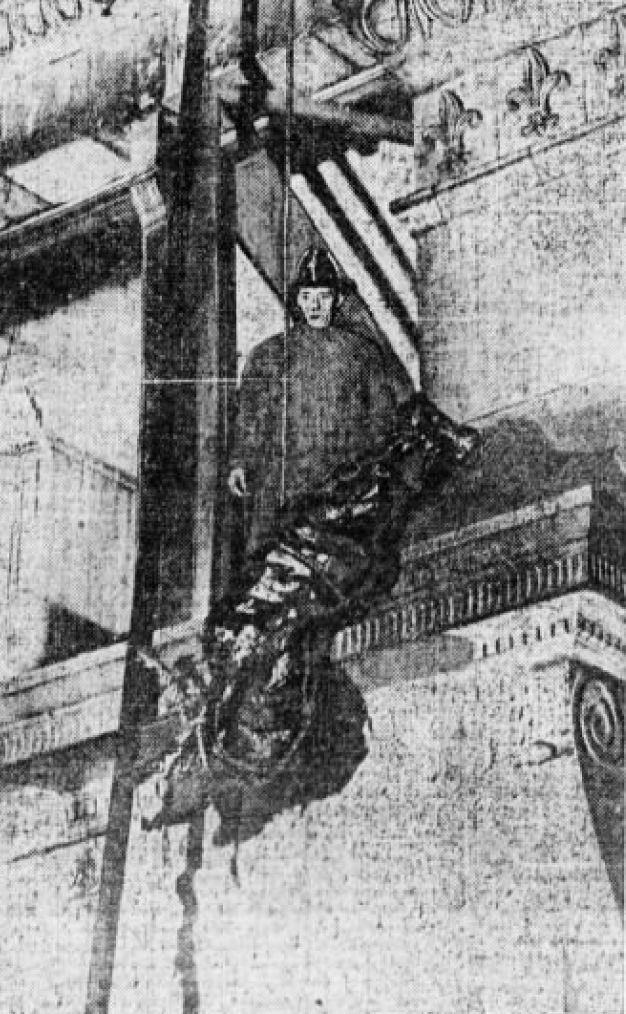

Preparing temporary coffins to hold the remaining dead (above). A fireman lowering a body down from one of the upper floors (below). From The Brooklyn Eagle, March 26, 1911.

At the end of East 26th Street was the Charities Pier, where people were usually taken to the Blackwell’s Island almshouse. It was popularly referred to as “Misery Lane.” Used as an emergency morgue after the General Slocum disaster, it was once again called into service. As the last bodies were being taken out of the building, the doors to the morgue were opened, and the viewing line stretched around the block. The pier was periodically filled with screams of relatives who had identified their loved ones. Some were only able to be recognized by their watches, jewelry, shoes, hairstyles, or fragments of clothes.

A sketch showing folks looking for their loved ones at the temporary morgue on 26th Street. From The New York Tribune, March 27, 1911.

146 people died on that early spring Saturday. They included parents and children, siblings, and cousins that had worked together. 123 of the victims were women, and their ages ranged from 43 to only 14. Many lived in the nearby Lower East Side or Greenwich Village, while others commuted from Yorkville, Harlem, and Brooklyn. They left behind whole families, aging parents, young siblings, relatives left alone in the country, and sweethearts, all of whom experienced a tremendous loss. The funerals began the next day and continued throughout the next weeks as more workers were identified and arrangements could be made.

Scene at the Bellevue Morgue as a funeral is set to take place. From The New York World, Evening Edition, March 27, 1911.

“The Real Triangle,” drawn by John Sloan for The New York Call, March 27, 1911. The newspaper reads “Employer’s Liability Bill,” and the knife driven into it says “Courts.”

On April 5th the ILGWU arranged a day of mourning and a mass funeral for the unidentified victims. Thousands of workers and members of 60 unions gathered and marched silently through the rain-soaked streets, accompanying an empty coffin symbolizing the unidentified workers who had died. An estimated 400,000 people participated in or watched the march, with people donning ribbons or hoisting banners that said “We Mourn Our Loss.” The remains of the unidentified were buried together in Evergreen Cemetery. They were finally identified in 2011, and a new stone with their names was placed in front of the old one.

Union members carrying banners saying “We Mourn Our Loss.” From Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, April 20, 1911, Volume 112, Issue 2902.

The procession marching up 5th Avenue, with the Washington Arch seen through the mist. Note the people along the sidewalk, there to pay their respects. From The New York Tribune, April 6, 1911.

Blanck and Harris were acquitted of any wrongdoing.

However, workers continued to call for better working conditions. Their signs are decorated with black bunting and ribbons to remember the workers that were killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. From Hampton’s Magazine, June 1911, Volume 26, Number 6.

Select sources

We Shall Not be Moved: The Women’s Factory Strike of 1909 by Joan Dash

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and Sweatshop Reform in American History by Suzanne Lieurance

The Rising of the Women: Feminist Solidarity and Class Conflict, 1880-1917 by Meredith Tax

Triangle: The Fire that Changed America by Dave Von Drehle