Have you ever walked around New York City and found yourself wondering about the name of a certain street, park, building or place? Although many features have been built over, demolished, or lost, there are still many traces of these places left in our modern cityscape.

The Battery

The Battery after the Revolution, c. 1785. Bowling Green still has the pedestal for the statue of King George III that was knocked down by a mob in 1776. The fence depicted in this view still surrounds the park. From Bowling Green by Spencer Trask.

Fort Amsterdam was built nearby in 1626, but the name was first applied to the area in 1683, when a battery of cannons was placed on a fortification facing the harbor. The temptation to extend the shoreline into the harbor was immense, and after the American Revolution Fort Amsterdam was demolished, and the debris was used as landfill.

Beaver Street

The Heere Gracht and Fish Bridge as they looked in 1659. From The Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1862.

The Dutch called this Bever Straet, as it was the center of beaver trading, which was a major economic boon for New Amsterdam. A small offshoot of the canal that ran down Broad Street called the Heere Gracht went down Beaver Street. By 1676 both canals had become badly polluted and were filled in.

The Bowery

Looking north up the busy Bowery from the 3rd Avenue elevated at Canal Street, c. 1890. From King’s handbook of New York City.

This was the original road out of New Amsterdam (not Broadway!). It followed the course of a native path, which led to the Werpoes settlement near the Collect Pond, and then to what is now Astor Place (which the natives called Kintecoying, the “crossroads of three nations”). It became the main road to the large farms of the Dutch West India Company, called bouwerij. By the 1650s, the road was simply known as The Bouwerij, which was Anglicized to The Bowery.

The Bronx

Map of Bronx Neck from the Patent of 1676. Bronck’s Emmaus was situated towards the bottom left. From The story of the Bronx, from the purchase made by the Dutch from the Indians in 1639 to the present day by Stephen Jenkins, 1912.

The Bronx: This was named after settler Jonas Bronck, who was not Dutch, but Danish or Swedish. He moved to a farm overlooking the Hell Gate in 1639, which he called Emmaus; the natives called it Ranachqua, “the end place.” Within several years, other European settlers were calling it Bronck’s land, which was eventually shortened to the Bronx.

Broadway

Looking down Broadway from St. Paul’s Chapel, 1835. From Glimpses of old New-York by Henry Collins Brown.

This originated with the Dutch Breede Weg, so this translation is quite literal as this means the Broad Way. The natives knew it as the Wickquasgeck Trail, named after the tribe that controlled the upper section of Manhattan (their main village was located in what is now Inwood Hill Park). Through the colonial era, Broadway ended near the city commons (now City Hall Park), and travelers used The Bowery to leave the city.

A map of Brooklyn showing the approximate boundaries of the original towns in Brooklyn, along with information about when they were annexed to Brooklyn. From The map, drawn around 1916, is from the Pictorial History of Brooklyn by Martin Henry Weyrauch.

Brooklyn: There were six original towns in Brooklyn, five of them Dutch and one of them English:

Nieuw Amersfoort: Flatlands, incorporated in 1636 and named after the city in Holland.

s’Gravenzende: Gravesend, founded in 1643 by Lady Deborah Moody, the first woman to be granted a settlement in the New World. This was the English town in Brooklyn.

Breuckelen: Brooklyn, founded in 1646 and named for the town in Holland.

Vlackebos: Flatbush, incorporated in 1651. The Dutch name means “wooden plains,” and this area was also known as Midwout, “middle woods.”

Nieuw Utrecht: Incorporated in 1652 and named for the province in Holland.

Boswijck: Bushwick, which was founded in 1661. The Dutch name means “town in the woods.”

The Collect Pond and environs, c. mid-18th century. The hills surrounding the pond were later leveled and used to fill in the pond after it was deemed too polluted and drained. From A Landmark History of New York by Albert Ulman.

Collect Pond: The pond was commonly called the Kalch Hoek, “lime shell point.” Several freshwater springs found here or nearby were an important water source for residents of New Amsterdam. For many years, people collected the water in large barrels and distributed it around the city; tea made from this water was considered to be a special treat.

A rendering of the train bridge over the Arthur Kill, 1888. From Scientific American, Vol. LVIII No. 26.

The Kills and Hooks: There are numerous features around the city that come from Dutch names, including kill, meaning “stream” (Arthur Kill was once Achter Kil, “stream on the other side”), bocht, “bay” (Wallabout Bay was originally Waal Bocht), and hoek, “hook” (such as in Red Hook, “Roode Hoek” and Bay Ridge, which was once known as Yellow Hook before it was renamed due to an unpleasant association with Yellow fever).

Washington Square in use as a parade ground, 1853. The 7th Regiment, New York State Militia, later dubbed the “Silk Stocking” regiment, is in formation as onlookers watch the maneuvers. From Fifth Avenue, old and new, 1824-1924 by Henry Collings Brown.

Greenwich Village: The original name for the area was Noortwijck, the “north district,” as it was once far outside the city limits. It was a popular spot for growing tobacco, a practice that the Dutch picked up from the Sapokanikan natives (their name, and the name for this place, meant “tobacco fields”). At some point, a settler from Long Island moved here, and he brought the name Grenwijck meaning “the pine district” (it was probably a reference to the pine barrens). This name stuck, and when the British took over in 1664, it was Anglicized to Greenwich.

Ships wrecked on the treacherous reefs of Hell Gate, c. 1825. The rocks were so dangerous that beginning in the 1830s the obstructions started to be removed. From King’s handbook of New York City (1892) by Moses King.

Hell Gate: This passage, Hellegat, was named by Adriaen Block in 1614. Block and his crew spent the winter on Manhattan after their ship, the Tyger, burned down. It is thought to mean “bright passage.” It was Anglicized to Hell Gate, but the variant Hurl Gate, likely a reference to the tumultuous waters, was used on maps for many years.

An area called Smit’s Vly, or “Smith’s Valley,” where Maiden Lane meets the East River. Along the shore is what will become Pearl Street. To the left is Cornelius Clopper’s blacksmith shop. From Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York by D.T. Valentine, 1861.

Maiden Lane: This was known as Maadge Paatje, the “maiden’s path,” as it ran along a small brook where Dutch women washed clothes.

An excerpt from the 1865 Sanitary & Topographical Map of the City and Island of New York by Egbert L. Viele showing the route of the watercourse through Washington Square and Greenwich Village.

Minetta Lane: The name of this watercourse comes from the native Manetta, meaning “evil spirit” or “snake water.” The Dutch called it Bestavaar’s Kill, and when the British took over, they Anglicized the native name into Minetta.

Buildings seen from the East River as they would have looked in 1652. The structures to the left (P-W) are situated along Pearl Street.. From New Amsterdam and its people by J. H. Innes.

Pearl Street: This was Paerl Straet, named after the shell middens that were left by natives. The shells were also used to pave the street, and glistened like pearls in the sunlight. In the early days of New Amsterdam, this was the waterfront. It was also sometimes known as De Waal, after the bulkhead that was built along it.

Spuyten Duyvil Creek from Tippet’s Hill, 1866. The factory on the spit of land jutting into the creek is the Johnson Iron Works, which produced Delafield cannons during the Civil War. When the Harlem River Ship canal was being dredged in the 1940s, the land was eliminated, although the big rock behind still stands, painted with a giant C for Columbia University, which has athletic fields nearby. From Manual of the corporation of the city of New York, 1866.

Spuyten Duyvil: This is the name for the watercourse that connects the Hudson River (known to the natives as Maikanetuk, “river that flows two ways”) and the Harlem River (known to the natives as Muscoota, “where rushes grow on the banks”). The natives, who had a village nearby called Shorakapok (“sitting down place,” “wading place,” or “place by the river”), called the watercourse Paparinemin, “place of a false start,” a name also applied to nearby Marble Hill. The origin of the name is rather murky, and befits a place where the two rivers meet. The most popular origin of the name comes from a local legend widely popularized by Washington Irving, where the unfortunate Anthony Van Corlaer crossed the creek in a storm, “in spite of the Devil,” and wound up drowning in the tumultuous waters. There are numerous variations on the name, including Spouting Devil, Spike & Devil, and “Spakent Heill” (a German variation).

The idyllic Turtle Bay, 1853. The mansion behind was owned by the Beekman family. From Old New York: From its earliest history to about the year 1868 by L. Bayard Smith.

Turtle Bay: Dutch settlers named the bay here after a deutal, a “bent blade,” as they thought that the bay was a similar shape. This was eventually Anglicized to Turtle Bay.

Two men meeting along Wall Street, 1653. From The Story of a Street: A Narrative History of Wall Street by Frederick Trevor Hill.

Wall Street: The wall was built in 1653 by Dutch West India Company slaves on the order of Director General Peter Stuyvesant, who wanted to protect the city from the English, as the First Anglo-Dutch War was underway. To get into town, people could take the Land Gate (at Broadway), or the Water Gate (at Pearl Street). A street was laid out on the southern side of the palisade, and this became the Walstraat. The palisade remained in place until 1699, when the British demolished it.

Note: There are numerous spellings for old Dutch names, as well as the Anglicized versions. I have done my best to approximate these for easy comprehension.

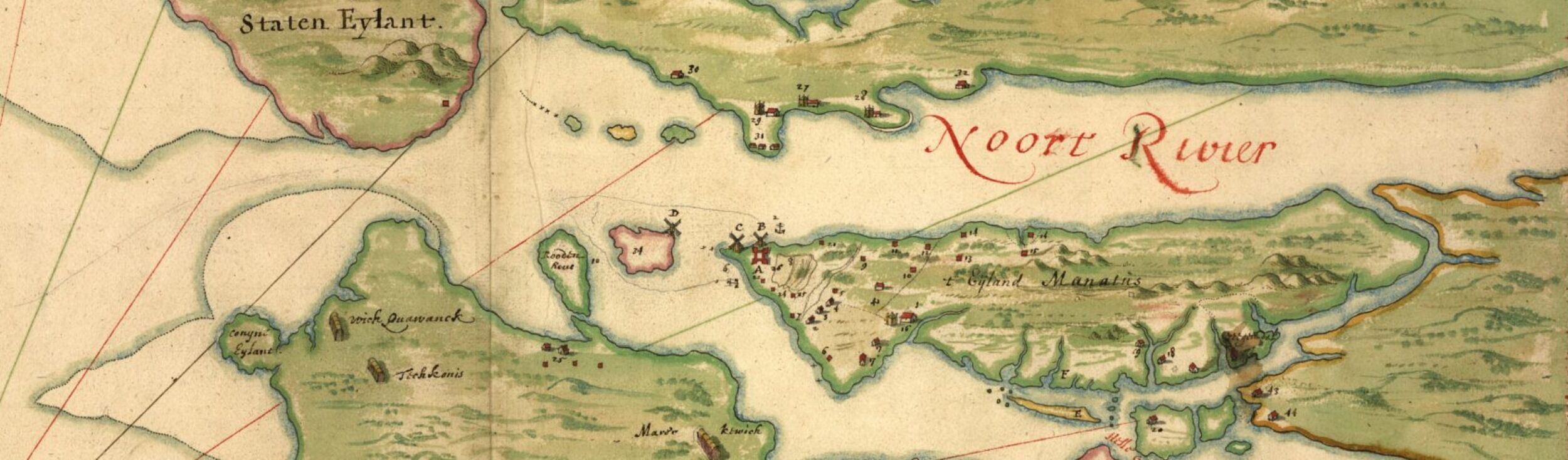

Two depictions of the island of Manhattan as it appeared in 1639. Both are copies from earlier maps. The top shows the Castello Copy of Manhattan situated on the North River (Manatvs gelegen op de Noot [sic] Riuier or Manatvs gelegen op de Noort Rivier), and the bottom shows a similar view taken from the original, known as the Harrisse Copy. From Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes’ Iconography of Manhattan Island, Volume 2.

Select sources

Brooklyn by Name: How the Neighborhoods, Streets, Parks, Bridges and More Got Their Names by Leonard Bernado and Jennifer Weiss

The Bronx River in History & Folklore by Stephen Paul Devillo

Names of New York: Discovering the City’s Past, Present, and Future Through Its Place-Names by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Manhattan to Minisink: American Indian Place Names of Greater New York and Vicinity by Robert S. Grumet.

History in Asphalt: The Origin of Bronx Street and Place Names by John McNamara

Manhattan Street Names Past and Present by Don Rogerson