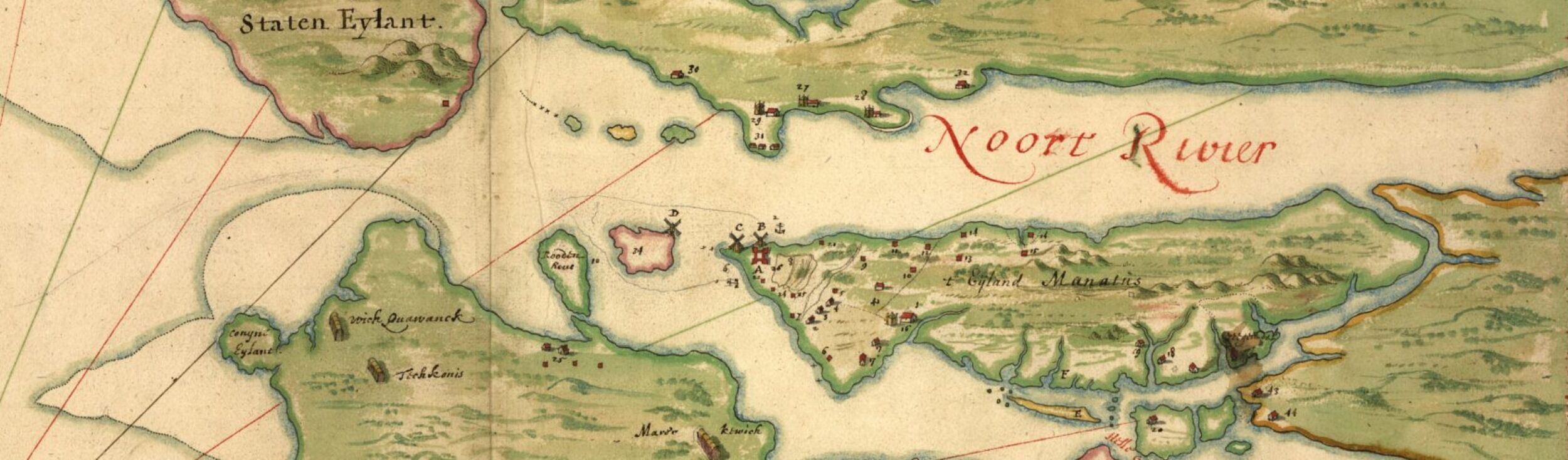

Recreational cannabis usage in New York City can generally be traced back to the infamous Harlem “tea pads,” underground clubs where jazz musicians gathered to talk, jam, and enjoy “cannabis cigarettes.” Many of these musicians had been barred from larger institutions that were whites-only such as the Apollo and Cotton Club.

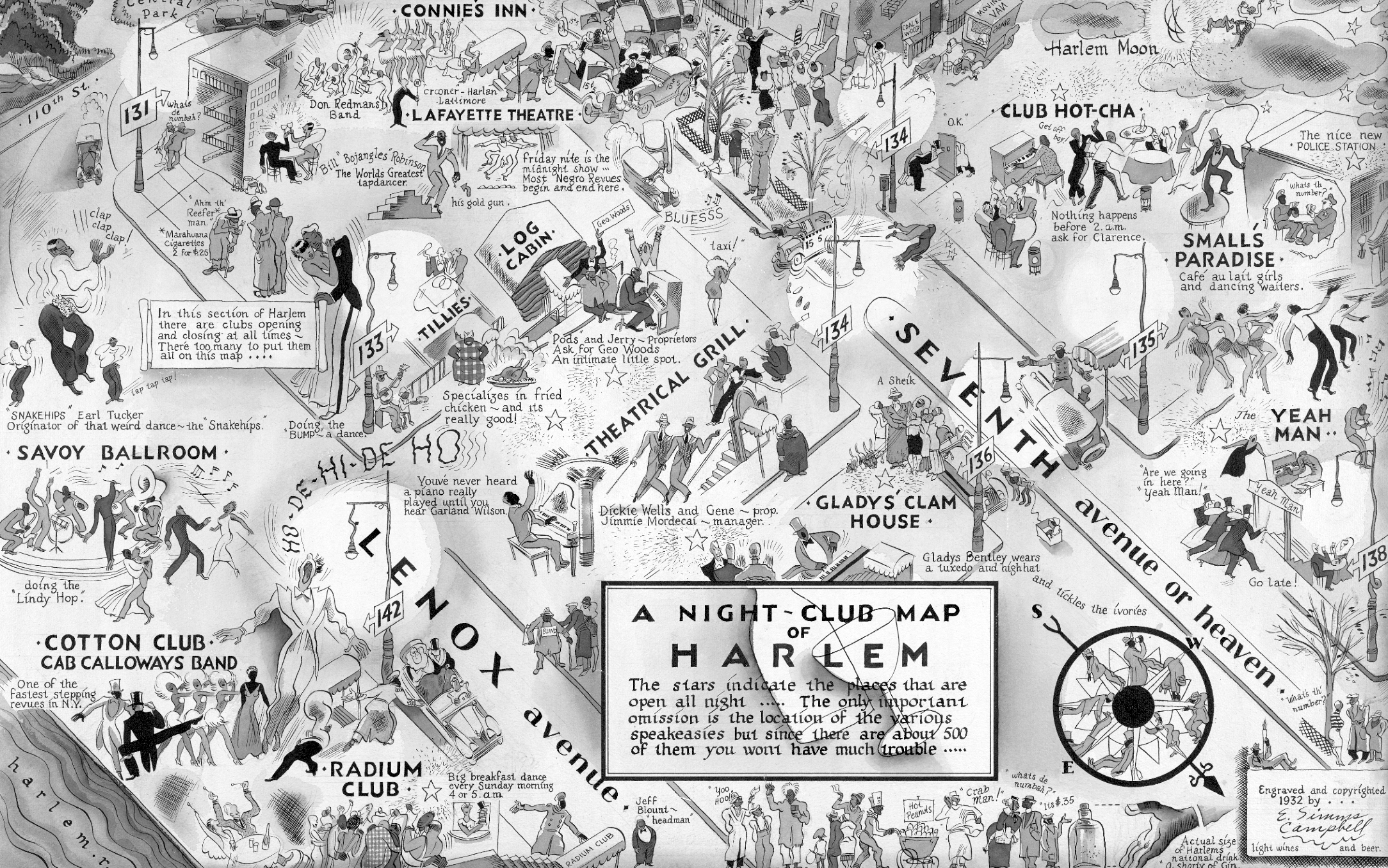

This night-club map of Harlem from 1932 shows some lively street scenes in the neighborhood. On the upper left the “Reefer Man” is offering marihuana cigarettes for sale, asking $25 for two. A larger version of the map where you can zoom in to explore the details of the map can be accessed here.

Drawn by cartoonist E. Simms Campbell for Manhattan Magazine: A Weekly for Wakeful New Yorkers, Vol 1, No. 1, January 18, 1933

Recreational cannabis usage in New York City can generally be traced back to the infamous Harlem “tea pads,” underground clubs where jazz musicians gathered to talk, jam, and enjoy “cannabis cigarettes.” Many of these musicians had been barred from larger institutions that were whites-only such as the Apollo and Cotton Club.

By the 1930s, hundreds of these tea pads were located in Harlem, and as jazz became more popular, they spread to other areas of the city. According to the LaGuardia Committee report, “Usually, each ‘tea-pad’ has comfortable furniture, a radio, victrola or, as in most instances, a rented nickelodeon. The lighting is more or less uniformly dim, with blue predominating. An incense burner is considered part of the furnishings.”

Harry Anslinger’s notorious Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) targeted these tea pads both during and after alcohol Prohibition. Anslinger enthusiastically testified before Congress about the evils of cannabis, compiling his infamous “gore file” that associated cannabis use with violence, insanity, and murder. In 1937 the Marihuana Tax Act (MTA) was passed, effectively outlawing the non-medical, untaxed possession or sale of cannabis.

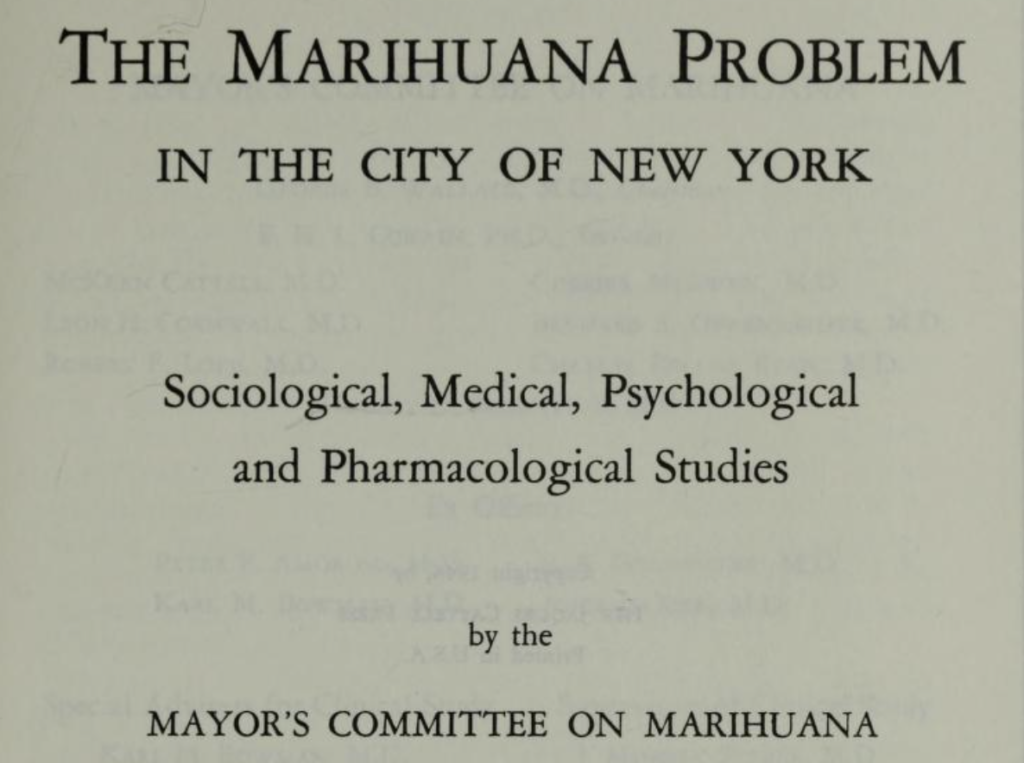

The frontispiece of The Marihuana Problem in the City of New York, published in 1944. Often referred to as the LaGuardia Commission report, it observed that “there was found no direct relationship between the commission of crimes of violence and marihuana.”

New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia strongly opposed this, and created a special commission of 31 physicians, psychologists, chemists, and sociologists to explore the effects of cannabis. The multi-year study, published in 1944 and written by the New York Academy of Medicine, refuted Anslinger’s lurid claims, concluding that “the publicity concerning the catastrophic effects of marijuana smoking in New York City is unfounded.” Anslinger responded by lobbying the American Medical Association to publicly criticize the report and deem it unscientific, which effectively stifled any dissent.

At this point, less than 10% of all Americans had tried marijuana, and a disproportionate number of those arrested were minorities. Interestingly, during La Guardia’s mayoral tenure, the NYPD largely ignored marijuana users in open defiance of Anslinger. Larger-scale recreational use in New York City didn’t happen until the 1960s, when more young people were able to access it.

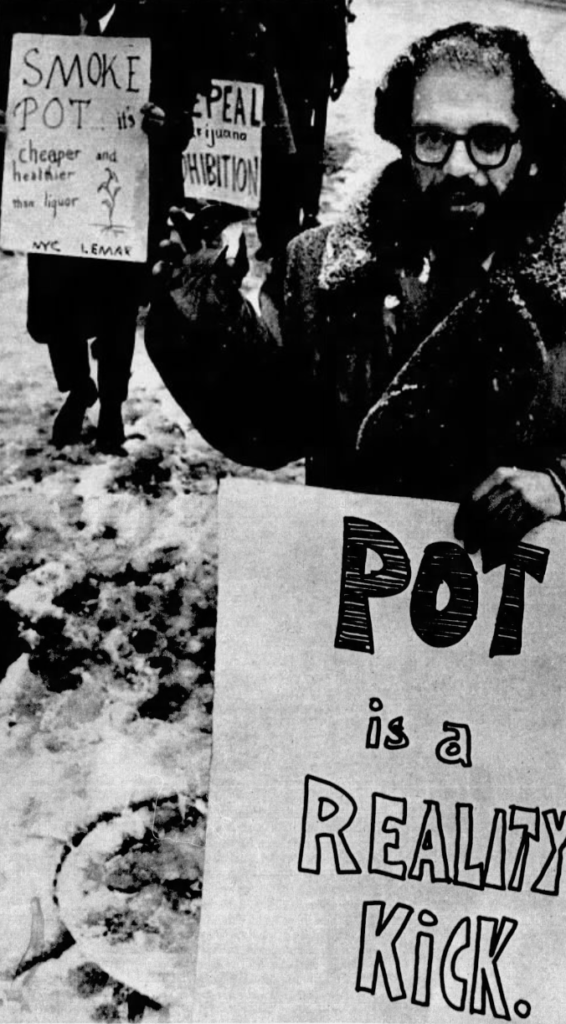

Allen Ginsberg at a LeMar rally in January 1965, with a sign that says “Pot is a Reality Kick.” The Buffalo News, August 21, 1965.

Greenwich Village, which had long been a hotbed of creatives, became equally well-known as a spot for people to procure and consume cannabis. Members of the Beats, including writers Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg, frequently used cannabis as a creative outlet. Ginsberg was an active advocate for using cannabis, and was a founding member of Legalize Marijuana (LeMar). LeMar held demonstrations outside of the imposing Women’s House of Detention, where Ginsberg and others would walk around with signs, including “Pot is Fun.”

In his 1967 work “Hustlers, Beats, and Others,” sociologist Ned Polsky observed that cannabis use had moved on from jazz musicians to the Beats to larger swaths of the population, although the Beats significantly “convinced many sectors of the public that the Federal Narcotic Bureau’s myths about marihuana – the notions that marihuana is a significant cause of crime, insanity, and heroin addiction – were indubitably myths.”

A note on the usage of cannabis: Biological taxonomists classify marijuana and hemp (which isn’t psychoactive) plants in the genus Cannabis, and this is the term that will be used. Cannabis is often interchangeably used with the term marijuana, which was often spelled as marijuana or a similar variant in the past (marijuana is derived from Spanish, and the name change was a deliberate attempt by prohibitionists such as Harry Anslinger to stir up racial fears by associating the substance with those painted as dangerous individuals).

Select sources

Cannabis: A History by Martin Booth

Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany by Robert Clarke and Mark Merlin

Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America by Jonathan Gill

The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues, a History of Greenwich Village by John Strausbaugh