In the first years of the 20th century, steam trains still ran into midtown Manhattan, a relic of the past that would soon be replaced by widespread electrification. In Brooklyn, the elevated lines were electrified beginning in 1898, followed by the Manhattan elevated lines in 1901. The great Pennsylvania Railroad was in the early stages of planning a new station that would host electric engines, and construction was commencing on the first sections of the subway, which would be powered by electricity, with spacious, light-filled stations close to the street for the convenience of passengers.

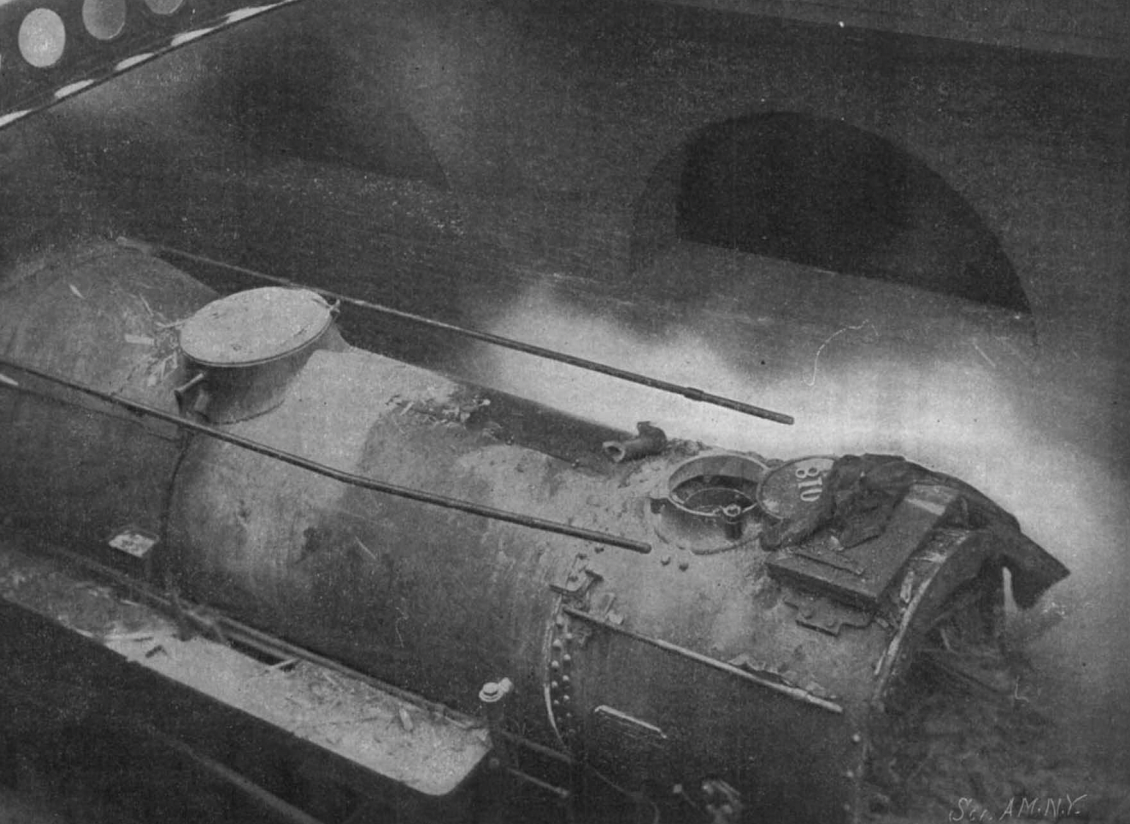

The wrecked engine of Train No. 118, which rear-ended the train waiting to be cleared to enter the train yard. From Scientific American, January 18th, 1902.

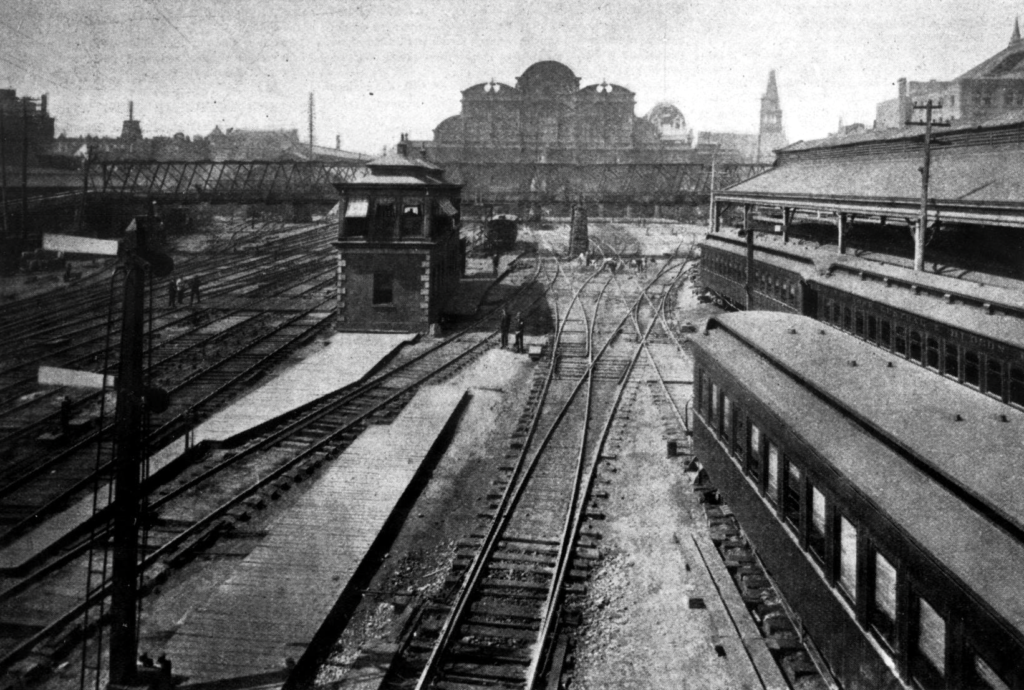

However, the New York Central still continued to operate steam engines into Grand Central Station.* They ran through the Park Avenue tunnel (also commonly called the Yorkville tunnel), which stretched from 96th Street to 56th Street. The railroad had lowered the tracks into an open cut as part of an improvement scheme, which also involved the construction of the massive stone viaduct stretching up to Harlem. South of 56th Street the tracks were in an open cut, leading to a large train yard, criss-crossed by pedestrian bridges. Local residents complained about the open cut above 56th Street, which was roofed over, creating a tunnel with periodic vents to let out steam and soot from below. It was this exhaust that would contribute to a most deadly accident.

The vast yards behind Grand Central Depot, looking south towards the train shed, through which an estimated 30,000 people went through each day. To the north of this is the entrance to the Park Avenue tunnel. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, June 6th, 1891, Volume 72, Issue 1864.

On the morning of January 8th, 1902, Train No. 223, which had originated in Danbury, was waiting near the mouth of the Park Avenue tunnel for a green signal, which had been delayed by some work in the yard. Train No, 118 from White Plains, which was a few minutes behind schedule, approached on the same track, passing a clear signal. The other signals, along with warning lanterns, were supposedly obscured by smoke and fog, and engineer John Wisker proceeded at at least 20 miles per hour (some sources say as fast as 35 miles an hour) before the other train came into view. By then it was too late to avoid a crash, and at 8:20 AM, train No. 118 rear-ended train No. 223 with such ferocity that the last car telescoped, killing numerous commuters instantly, and trapping many more.

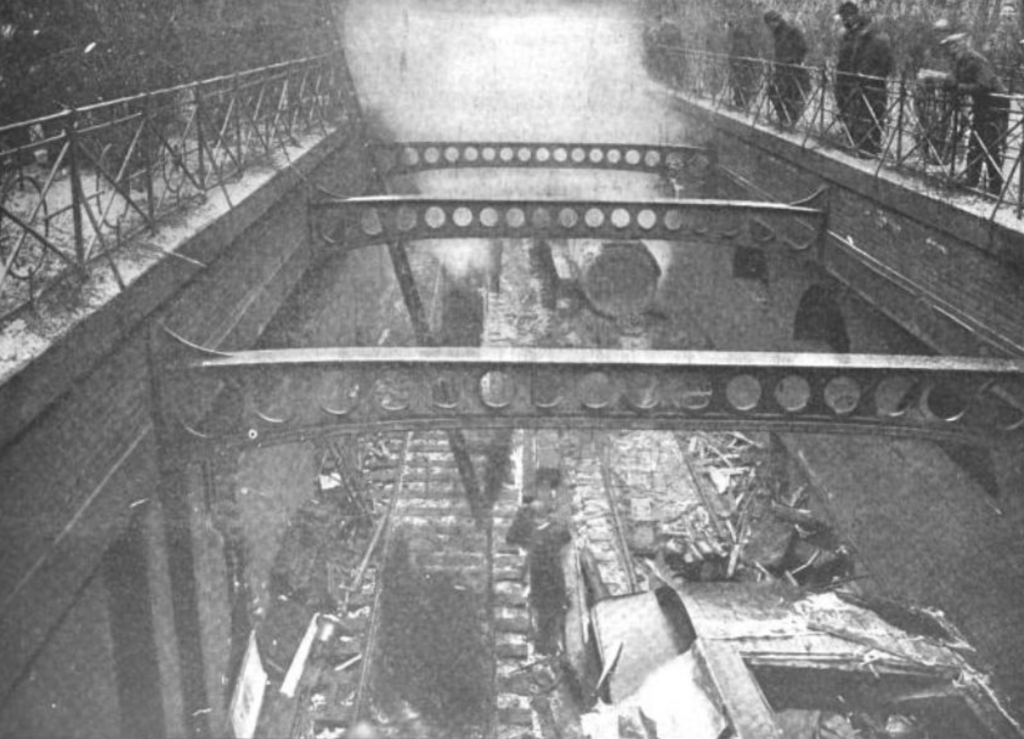

The wreckage viewed from above. It was foggy and snowing that morning, which may have also contributed to some of the poor visibility. From Collier’s Weekly, January 18th, 1902.

In the confusion, some people jumped out of the windows, injuring themselves on the glass or in the fall. Others were scalded badly by steam. The crash was heard from above, and fortunately help was quick to arrive, with firemen extending ladders into the tunnel and pulling out the injured by ropes. Those who could walk exited the tunnel and continued to Grand Central. Another disaster was averted by Frank Manent, the quick-thinking brakeman from train No. 118, who ran ahead of the wreck to stop trains from going up the adjacent track. Nearly all of those killed were from New Rochelle, as train No. 223 reserved the last car for passengers alighting there, and that city was plunged into mourning. Fifteen people perished that day, with two more succumbing to their injuries in the next week, bringing the death total to seventeen, and many more injured recovering in city hospitals.

Onlookers gathering on Park Avenue to view the wreckage, as rescuers work in the tunnel to help the injured and recover bodies. From Collier’s Weekly, January 18th, 1902.

The response to the wreck was swift, with officials blaming John M. Whisker for his haste, although he was later acquitted. Another target was William J. Wilgus, chief engineer of the New York Central, while others pointed fingers at the New York Central. The railroad had in fact studied the possibilities for electrification beginning in 1899, but neglected to make significant changes. A similar, albeit less deadly, collision had occurred in the Park Avenue tunnel in 1891, and it was increasingly clear that the railroad would need to proceed with electrification, which was underscored in May 1903 when the New York State Legislature passed an act banning steam locomotives from entering Manhattan after June 1908.

The first test run of an electric train to Grand Central, 1906. Construction was already commencing on Grand Central Terminal on the eastern side. Trains continued running throughout the entire course of construction. From The Street Railway Journal, Volume XXX, Number 15.

Fortunately for the New York Central, chief engineer William J. Wilgus had previously worked on electrification projects for railroads and consulted with many leading engineers in the field. These experiences informed his decision to put forth a monumental proposal for a novel double-deck underground train yard, a stately terminal building, and, perhaps most importantly for the railroad’s board and investors, a plan to “wealth from the air” and utilize the space above the tracks for buildings that could bring revenue to the railroad and pay for part or all of the project. This was just the ticket for the railroad, which began running the first electric trains in 1906, and included in the design for the new terminal a celebration of electricity, including magnificent chandeliers with bare lightbulbs, which have become an iconic feature.

A depiction of Grand Central Terminal, showing parts of the Terminal City complex. What William J. Wilgus called taking “wealth from the air” is what we know very well in the city as air rights, and these blocks would soon fill up, and, as we know, be torn down and rebuilt once again. From Scientific American, June 17th, 1911.

*Note that at the time of the crash, it was known as Grand Central Station, as Grand Central Depot (1871) had been expanded and renovated, and given a new title. The modern 1913 station is Grand Central Terminal.

Select sources

Grand Central: Gateway to a Million Lives by John Belle and Maxinne R. Leighton

A Century of Subways: Celebrating 100 Years of New York’s Underground Railways by Brian J. Cudahy

Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America by Sam Roberts

The Wheels That Drove New York: A History of the New York City Transit System by Roger P. Roess and Gene Sansone

Grand Central’s Engineer: William J. Wilgus and the Planning of Modern Manhattan by Kurt C. Schlichting

Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (The History of NYC Series Book 2) by Mike Wallace

Newspaper articles

“Fifteen dead in tunnel collision and scores injured.” The Standard Union. January 8, 1902.

“Fifteen killed in rear end collision.” New York Times. January 9, 1902.

“Fifteen killed, thirty six hurt.” New-York Tribune. January 9, 1902.

“Seventeen killed in NYC tunnel.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 8, 1902.