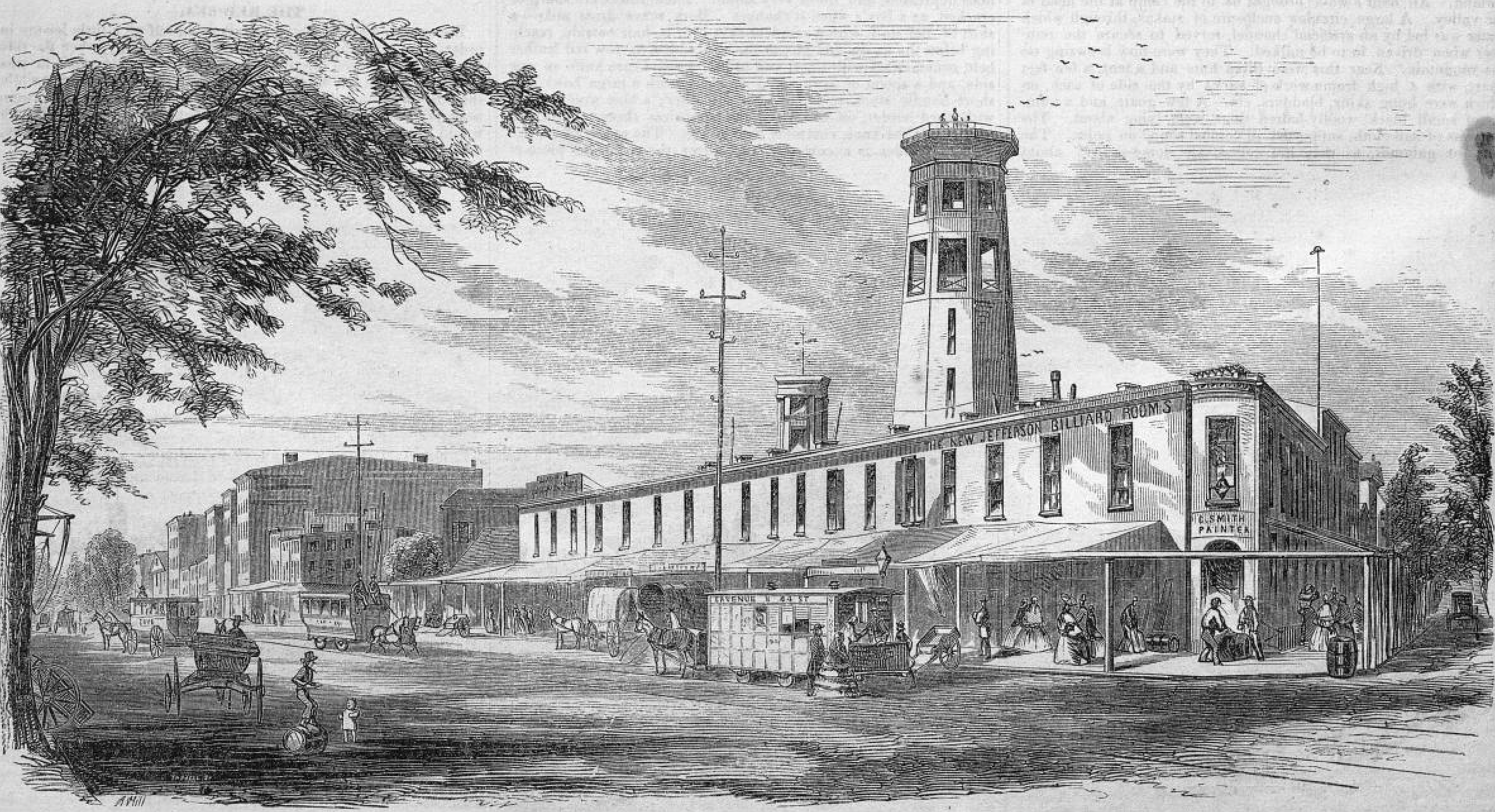

The Jefferson Market and Fire Tower, c. 1866. The police court was towards the back of the assembly room building. From Glimpses of Old New York by Henry Collins Brown.

Greenwich Village, once a sleepy hamlet far outside the boundaries of the city that formerly was dotted with country estates and provided refuge for those fleeing diseases like yellow fever and cholera, had become a burgeoning neighborhood by the 1830s. With an influx of new residents, they began petitioning the city for a new public market. The nearest one on Christopher Street was considered to be too small for their needs.

In 1832, the city purchased several lots along 6th Avenue for $32,500, hiring Smith and Roome to build the market building. The Common Council decided to name it after Thomas Jefferson, so it became the Jefferson Market. The market opened in January 1833, and was an immediate success. By 1836 a second market house was built just to the north, and three years later, they were enclosed, making the market one large complex.

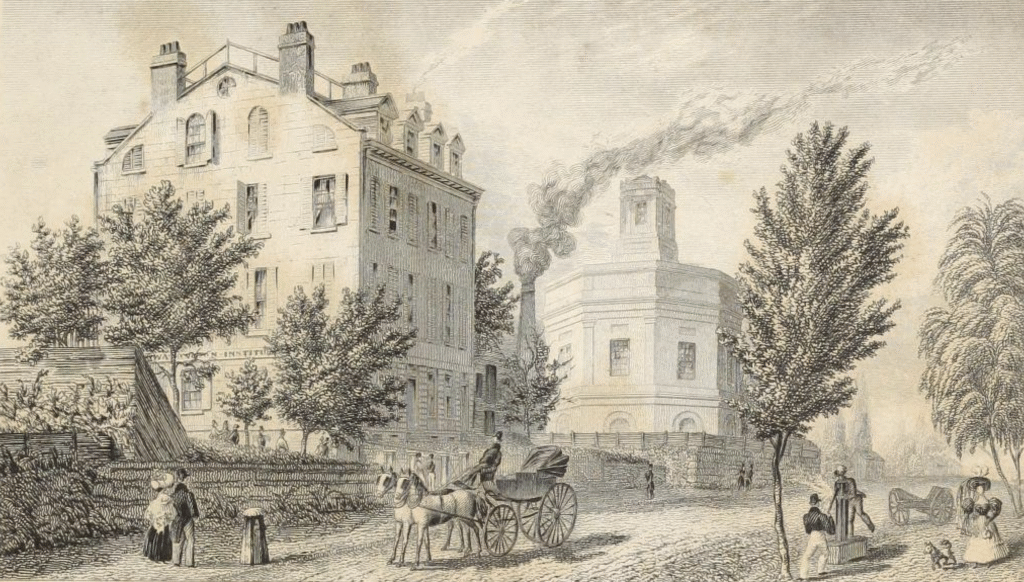

The octagonal New York City Reservoir, c. 1835. This view is looking up 4th Avenue towards Union Place (later Union Square). The structure on the right is the Washington Institute, a boarding school. From Views in New-York and its environs from accurate, characteristic, & picturesque drawings by Theodore S. Fay.

On the northern side of the complex along Amos Street (now West 10th Street), a well and cistern were dug, along with a 12 horsepower steam engine. This engine pumped water to the New York City Reservoir on Broadway between 13th and 14th Streets through iron pipes. The system could pump up to 21,000 gallons a day to the octagonal reservoir, which held over 230,000 gallons, and in turn branched off to fire hydrants that could be used by area fire engines.

The 6th Avenue side of the Jefferson Market, 1857. The market stalls offer access right from the sidewalk, and continue down Amos Street. At the time, there was also a billiards room on the second floor. From Ballou’s Pictorial, October 17, 1857.

A large wooden fire tower was also constructed along with the market, as the ever-present danger of fire required towers to be built across the city, although many of them were still made of wood. Three watchmen were posted in the tower on a rotating schedule to scan the surrounding area for fires, earning $1.75 each for their services. If they spotted a blaze, they could ring the 9,000 pound bell a predetermined number of times to signal where the fire was located. By 1842, a fire engine company was also stationed at the market, although they were not able to put a stop to a fire that engulfed the wooden tower and market in 1851.

Another wooden fire tower was planned, but the plot of land afforded to construct a new tower was smaller than intended. As a result, a tall iron tower was constructed by James L. Miller & Company. Iron fire towers were being built all across the city, with many of them designed by architect James Bogardus; a fine example of a fire tower he designed in 1857 can still be seen in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem. The Jefferson Market tower’s bell was cast in Spain in 1752, transported to a Mexican monastery, and captured by General Winfield Scott during the Mexican-American War (in later years it was moved to a fire house in The Bronx, and then was incorporated into a WWI memorial tower, which still stands in Riverdale).

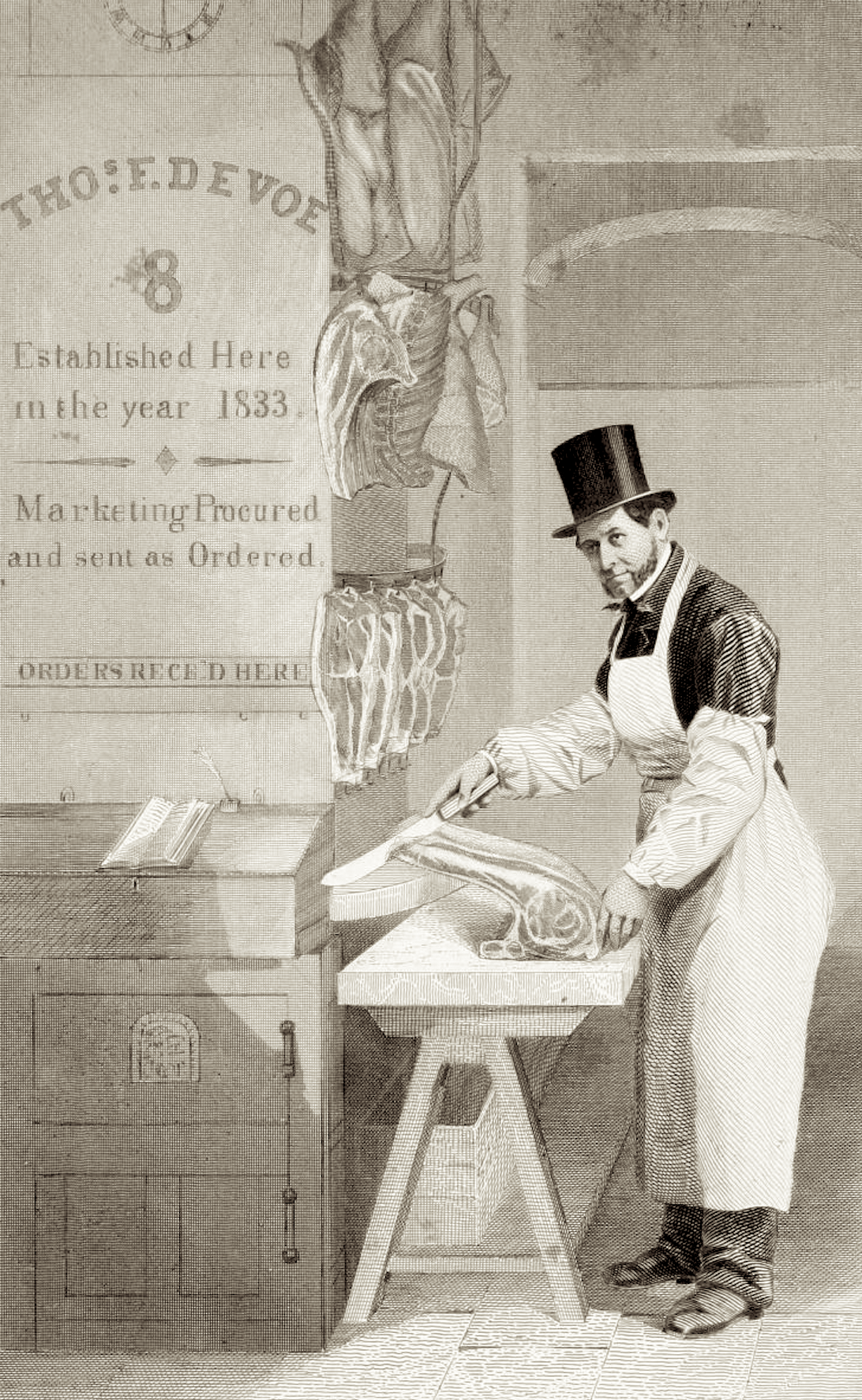

An illustration of butcher Thomas DeVoe, who operated out of the Jefferson Market from 1833 until 1872. DeVoe published two extraordinary books chronicling the considerable different types of meat and vegetables available both at the Jefferson Market and other markets in New York City, Brooklyn, Boston, and Philadelphia. This illustration is from The market assistant, containing a brief description of every article of human food sold in the public markets of the cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn, which is absolutely worth reading if you’d like to learn more about the types of foods that were available in the mid and late 19th Century in New York City and beyond.

By the late 1850s, the rebuilt Jefferson Market complex had expanded the market, and also grown to include a police station, courtrooms, a jail, a drill hall, and spaces for public meetings. Beginning in 1870, there was a movement to replace the older wooden structures, and the city invested $150,000 in new buildings. However, in a scene then common in the city, much of the funds were appropriated by Boss Tweed and his Tammany Hall cronies.

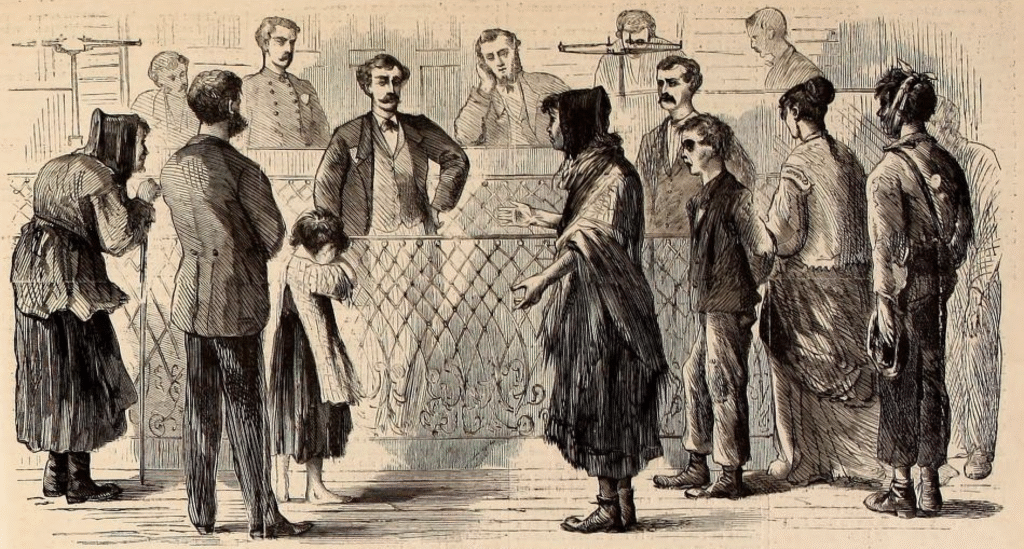

A scene showing people appearing at the Jefferson Market Courthouse, 1867. From Harper’s Weekly, December 14, 1867.

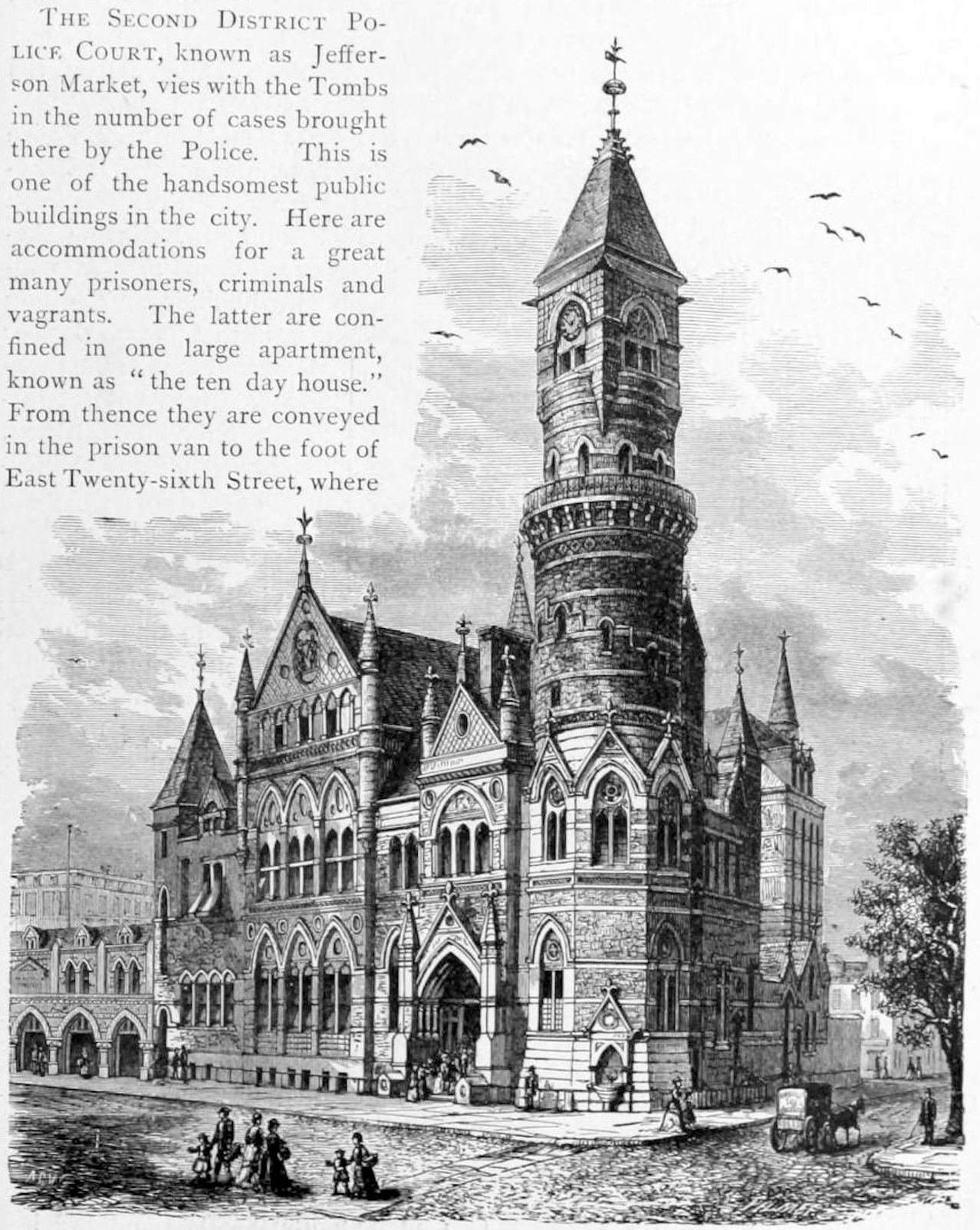

Another attempt was made to procure money for new buildings, which was successful. The improved complex included a magnificent courthouse with a 172-foot tower, along with a new jail and market building. They were designed by Frederick Clarke Withers and Calvert Vaux in the High Victorian Gothic style, with sumptuous red brick, limestone, and cast-iron details. Construction began in 1874, and was finished by 1877.

The new courthouse as it appeared from 6th Avenue, 1885. The market stalls can be seen on the left, and on the far right is the jail building. From Our police protectors: History of the New York police from the earliest period to the present time by Augustine Costello.

The court was the sight of numerous famous appearances, including Henry K. Thaw, who was brought in front of a magistrate after his infamous murder of Stanford White; Mae West, who spent a night in the prison after being arrested on obscenity charges for her controversial play “Sex”; and Stephen Crane, who defended a woman arrested for prostitution. In 1907, the city’s first night court was established. In 1909, shirtwaist company workers who had gone on strike were tried at the courthouse during the night hours, held next to prostitutes in an effort to humiliate them, and hauled before judges who handed down harsh sentences to discourage the other strikers.

The Women’s House of Detention and the Jefferson Market Courthouse, then under restoration, behind, 1966. H/T Stephen Carl Baldwin.

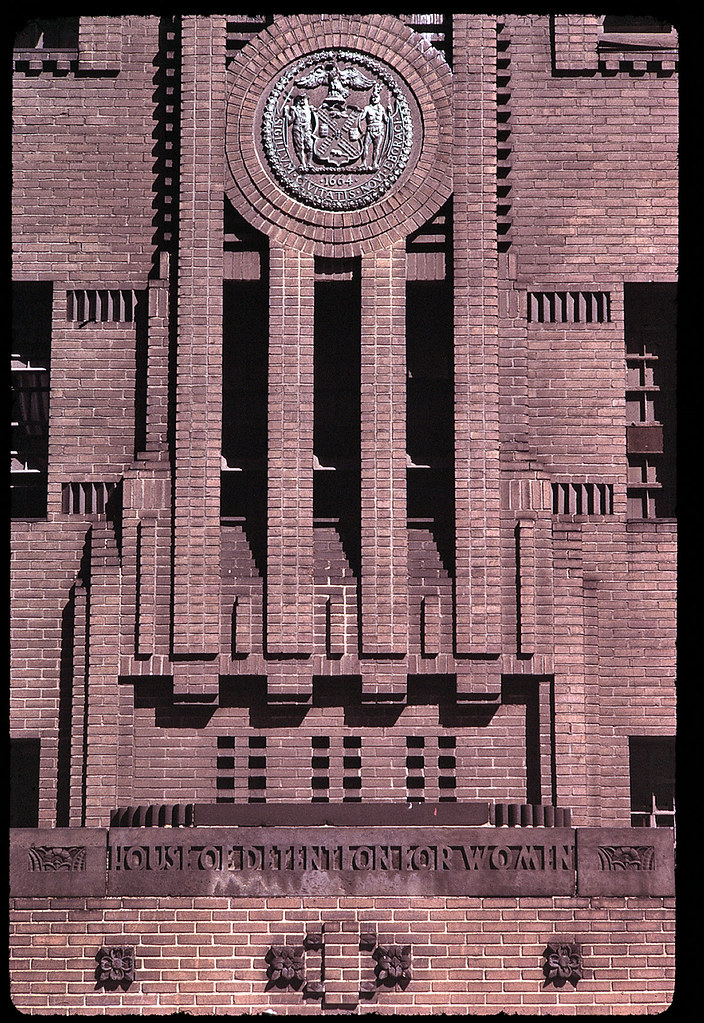

The imposing entrance to the Women’s House of Detention, 1966. Photo by Carl R. Baldwin.

The adjoining market and jail were razed in 1929 and replaced with the Women’s House of Detention. By 1950, the old courthouse was essentially abandoned, and was slated to be sold and replaced with an apartment building. Thankfully, Greenwich Village preservationists rallied to save it, and the building was lovingly restored. In 1967, the beautiful courthouse reopened as a branch of the New York Public Library. The Women’s House of Detention was demolished in 1974, and in its footprint a lovely community garden was planted, which still flourishes today.

Select sources

Around Washington Square: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village by Luther S. Harris

The Encyclopedia of New York City by Kenneth T. Jackson, Lisa Keller, and Nancy Flood

The Architecture of Frederick Clarke Withers and the Progress of the Gothic Revival after 1850 by Francis R. Kowsky

The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues, a History of Greenwich Village by John Strausbaugh

The AIA Guide to New York City by Norval White and Elliot Willensky