When the so-called “secret” subway line opened in February 1870, many New Yorkers were completely surprised that such a novel form of transit had been built, seemingly right under their noses and unbeknownst to “Boss” Tweed and his Tammany Hall cronies, operating across Broadway in the rooms of City Hall. The feat was pulled off by the intrepid Alfred Ely Beach, inventor, patent lawyer, and editor of Scientific American, who began the project with the intent to build pneumatic mail tubes and deftly changed plans.

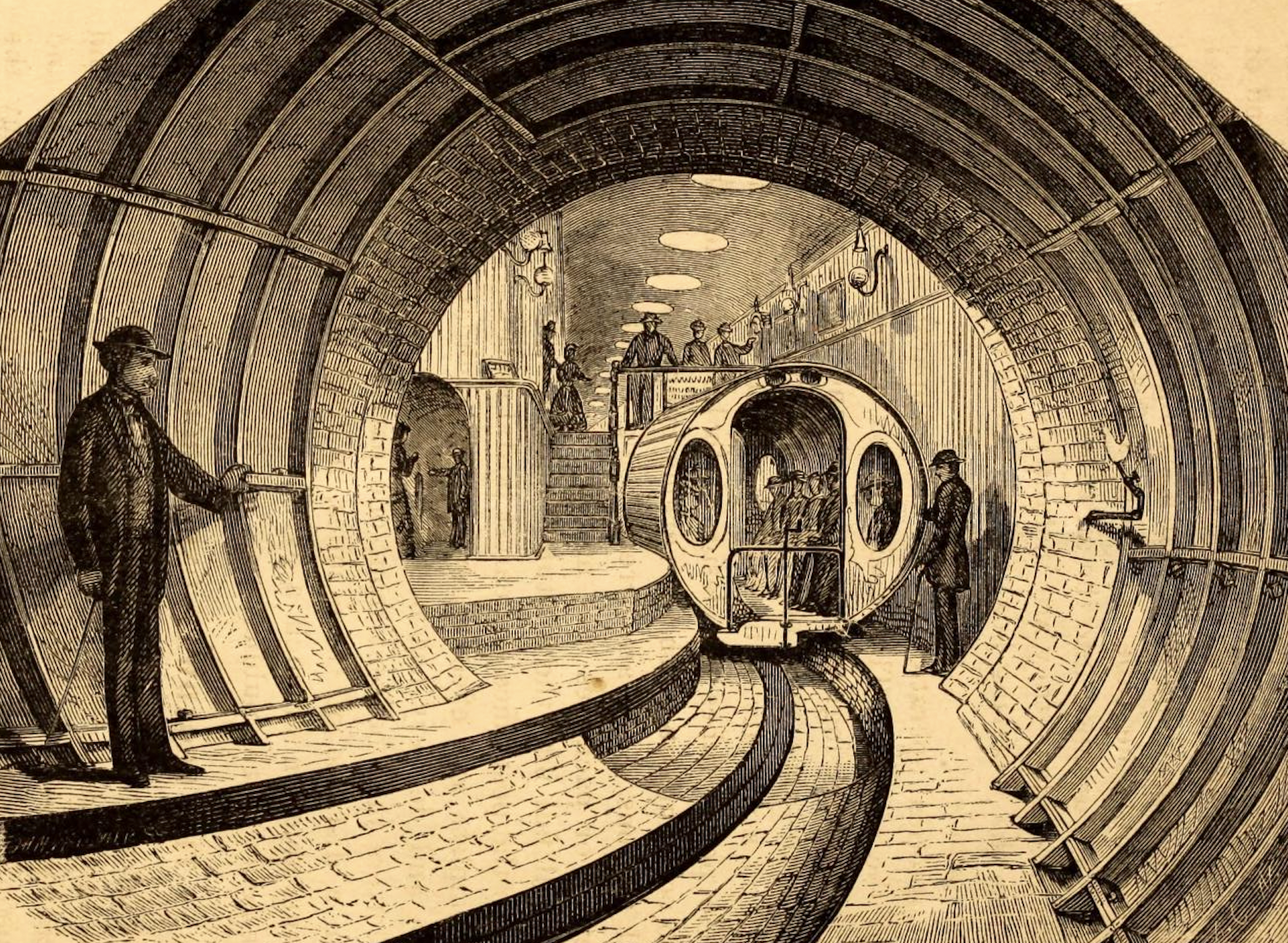

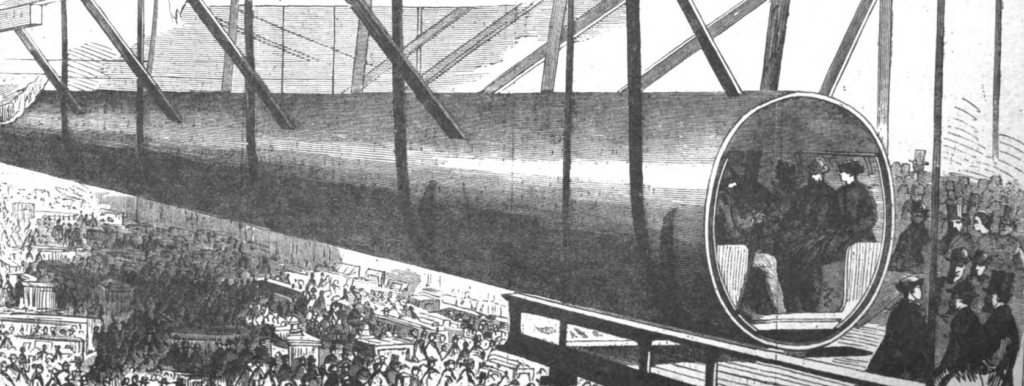

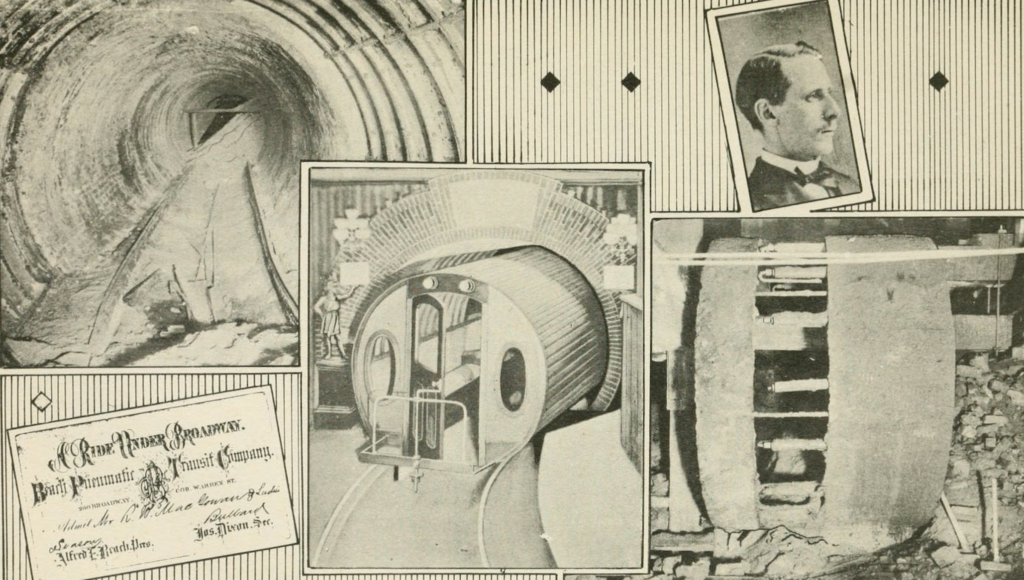

Looking from the tunnel towards the waiting passenger car. The blast of air that moved the car through the tunnel came from the opening on the left. Behind the car is the sumptuous waiting room, where visitors could relax and listen to piano music, admire the art on the walls, and watch the proceedings below. From Illustrated Description of the Broadway Underground Railway, published by the Beach Pneumatic Transit Railway Company, 1872.

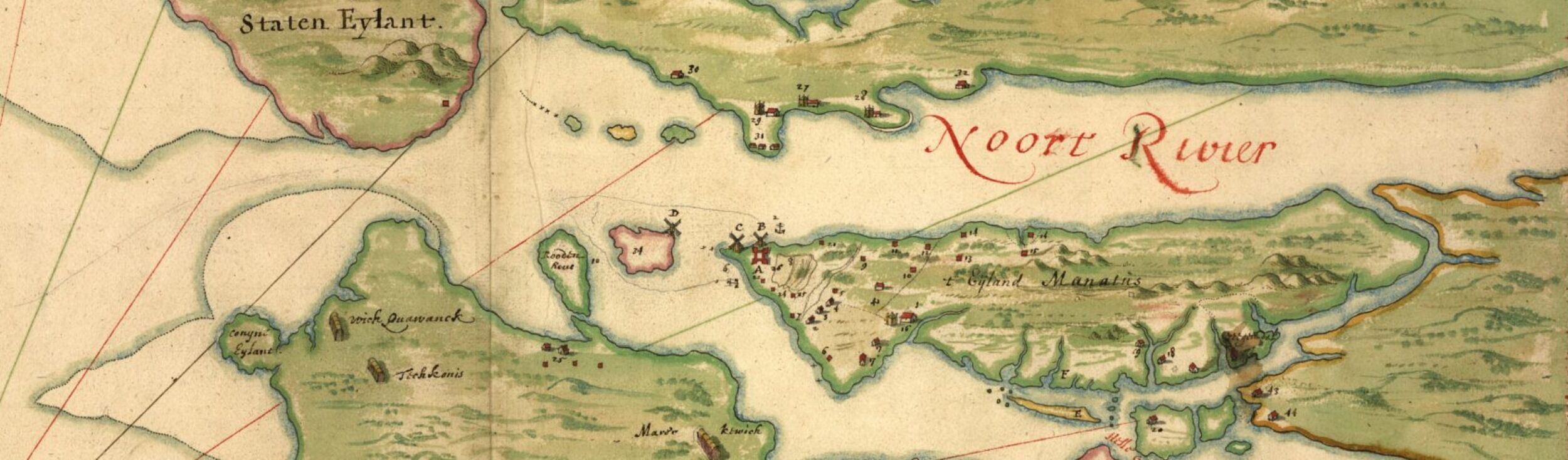

The Crystal Palace Pneumatic Railway stations at Holborn Street (top) and Sydenham (bottom). From The Pneumatic Dispatch, with Illustrations by Alfred Ely Beach, 1868.

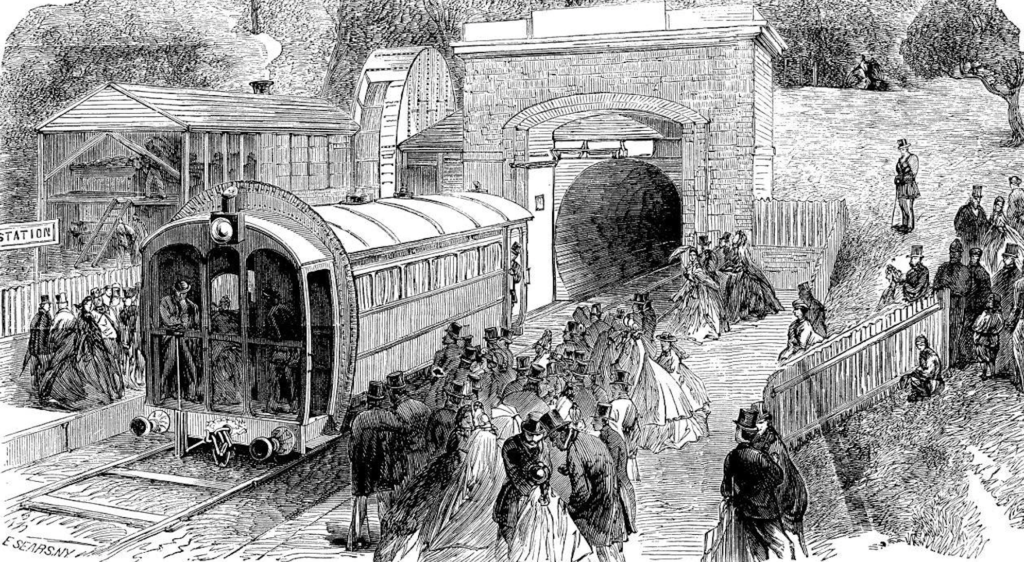

Pneumatic technology was not unknown, and it had been used to great effect for the Crystal Palace Pneumatic Railway in London in 1864. The experimental line ran for 600 yards, with each car seating 35 passengers and propelled by a steam-powered fan. Although it only operated for two months, it captured the fancy of many, and the pages of newspapers and magazines were filled with the words of those championing the delightfully nicknamed “atmospheric” railway and its “ethereal” science.

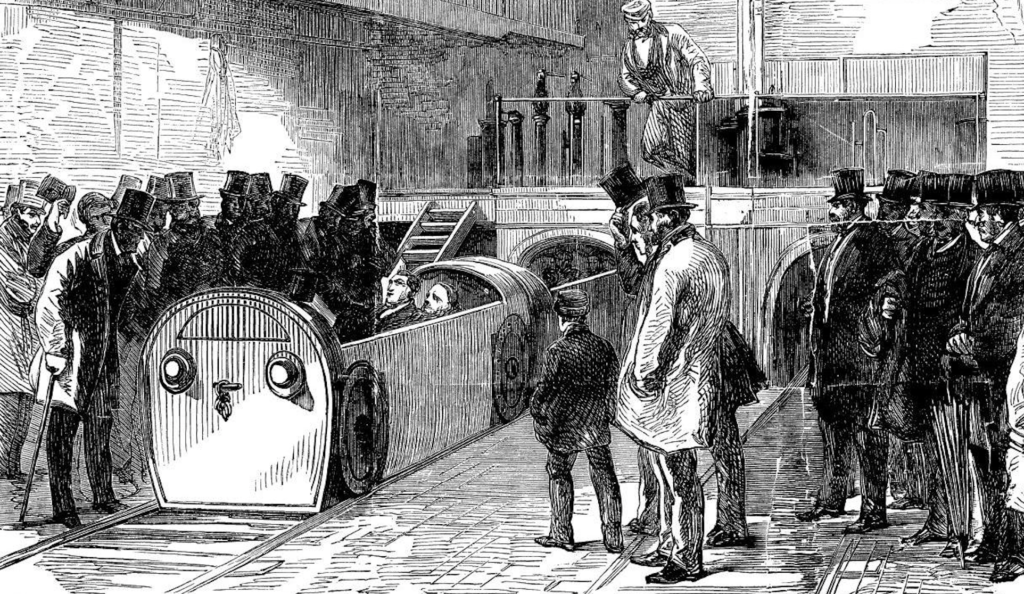

A sketch of the pneumatic passenger railway model. From Harper’s Weekly, October 19, 1867, Volume 11, No 564.

In September 1867, Alfred Ely Beach amazed visitors at the American Institute Fair, held at the 14th Street Armory, with a demonstration of his novel pneumatic passenger railway. built by the Holske Machine Company, the 107 foot long tube, 6 feet in diameter, was suspended from the ceiling. A 10 foot steam-powered fan moved a small passenger car, which could hold up to 12 people. It was a resounding success, with over 75,000 visitors taking a ride during the fair. Beach also demonstrated a pneumatic postal dispatch tube, which won awards, and would prove to be a key to constructing his underground line.

Broadway at Warren Street, c. 1905. The building on the lower right is the old Devlin and Bros. Company building, where the pneumatic railway started taking form. From City of New York by the L.H. Nelson Company

The Beach Pneumatic Transit Company was incorporated in 1868 for the purposes of constructing pneumatic mail tubes, and set up in the sub-basement of the Devlin and Bros. Company on the corner of Warren Street and Broadway. However, they ran into problems when a connection was rejected by the Postmaster General. A revision of the company charter circumvented this, and also allowed Beach to construct one larger tunnel instead of two smaller 54 inch ones. Such a tunnel could conveniently provide enough room for a passenger car to run.

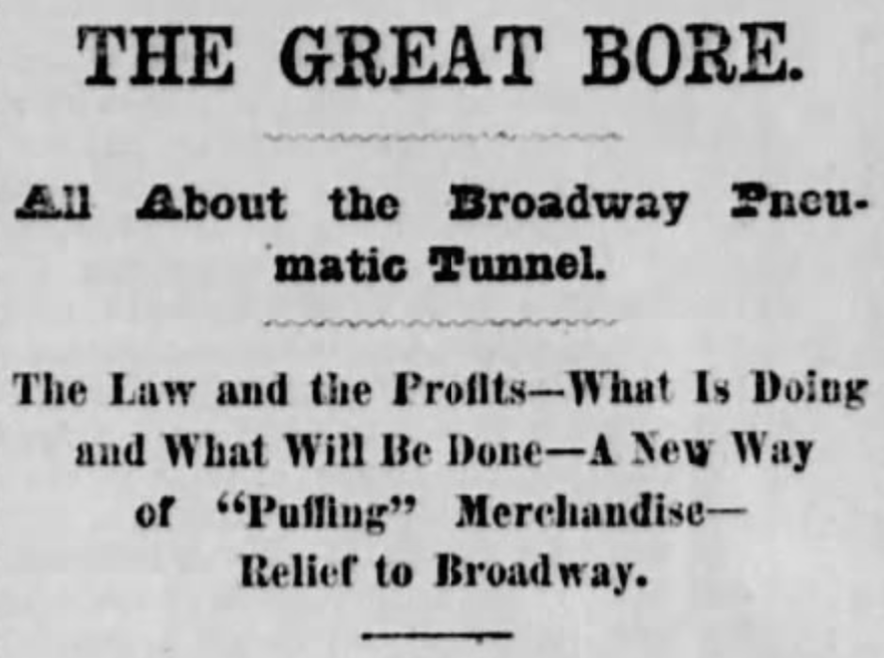

From The New York Daily Herald, Wednesday, December 29, 1869. The article noted that “the company worked and said nothing.”

Part of the reason that Beach was operating as he did, not in complete secret, but also without great fanfare, was due to the many machinations of Tammany Hall politicians. Led at the time by “Boss” William Maeger Tweed, the organization’s coffers and his pockets were lined by bribes and kickbacks from all over, including those from horse-car lines. Any threat to this, such as an independent underground subway, would cause trouble, so for Beach a little deception went a long way. Piles of dirt and debris began to be carted out along Warren Street at regular intervals. Construction continued apace through 1869, and several newspapers wrote about the novel pneumatic system, although some either obscured the fact or were unclear about the intent to carry passengers.

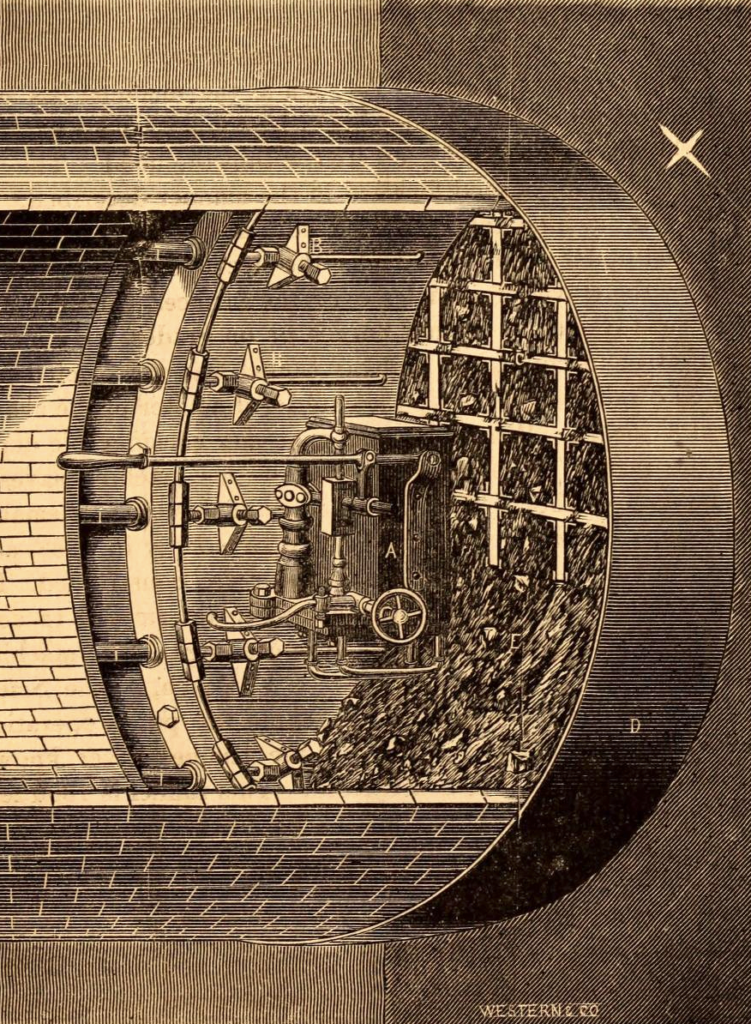

The tunneling machine in action, showing how the shield bore through dirt, sand, and rocks. Illustrated Description of the Broadway Underground Railway, published by the Beach Pneumatic Transit Railway Company, 1872.

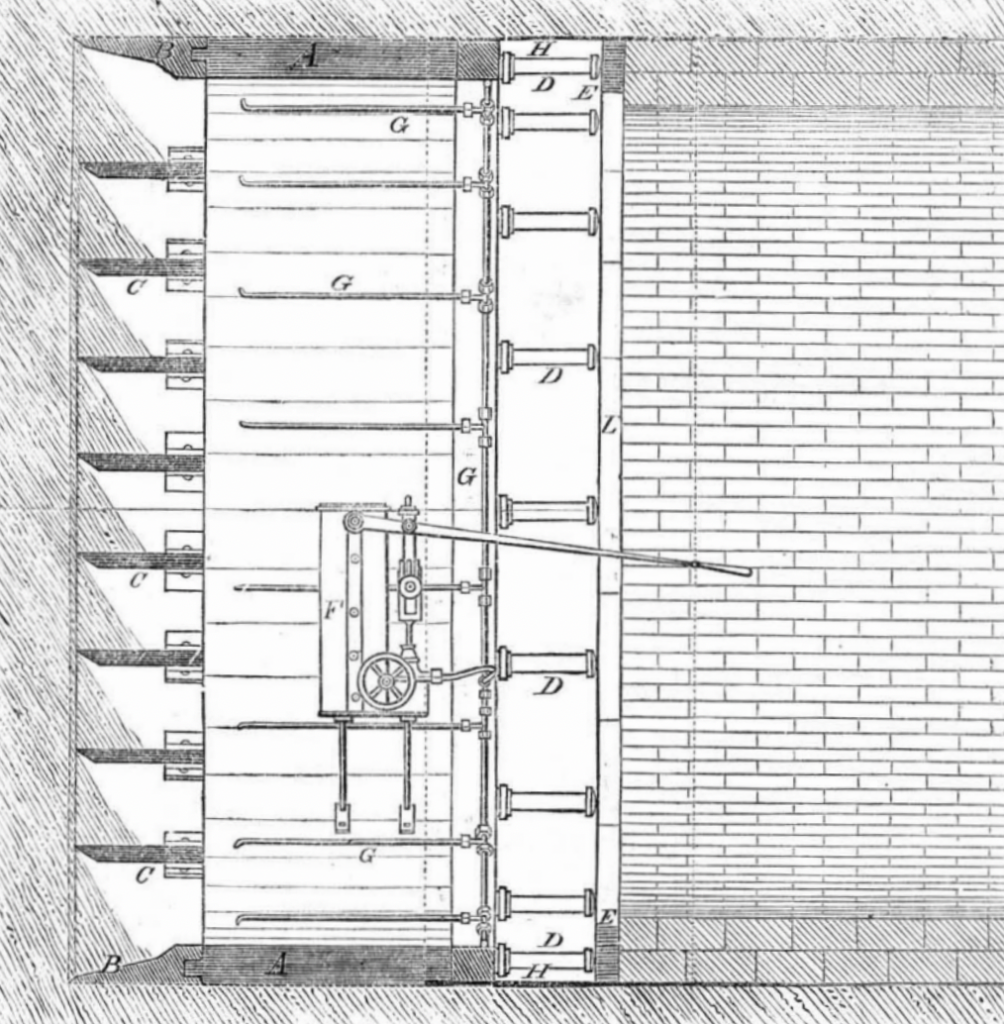

A side view of Beach’s tunnelling machine. The description of the shield is as follows: “The body of the shield is shown at A, and is simply a short tube of timberwork, backed by a heavy wrought iron ring, against which the hydraulic rams, D act to advance the entire machine. The front part of the shield is a heavy chilled iron ring, B, brought to a cutting edge, and crossed on the interior by shelves, C, also sharpened. Bearing blocks, E, of timber, are placed against the masonry, as shown, on which the rams press when the shield is advanced. F is the pump from which the water is carried to the rams by the pipes G. H is a hood of thin sheet steel within which the masonry is built, in rings of 16 inches length, the bricks interlocked. From Scientific American, March 5, 1870, Volume 22, Number 10.

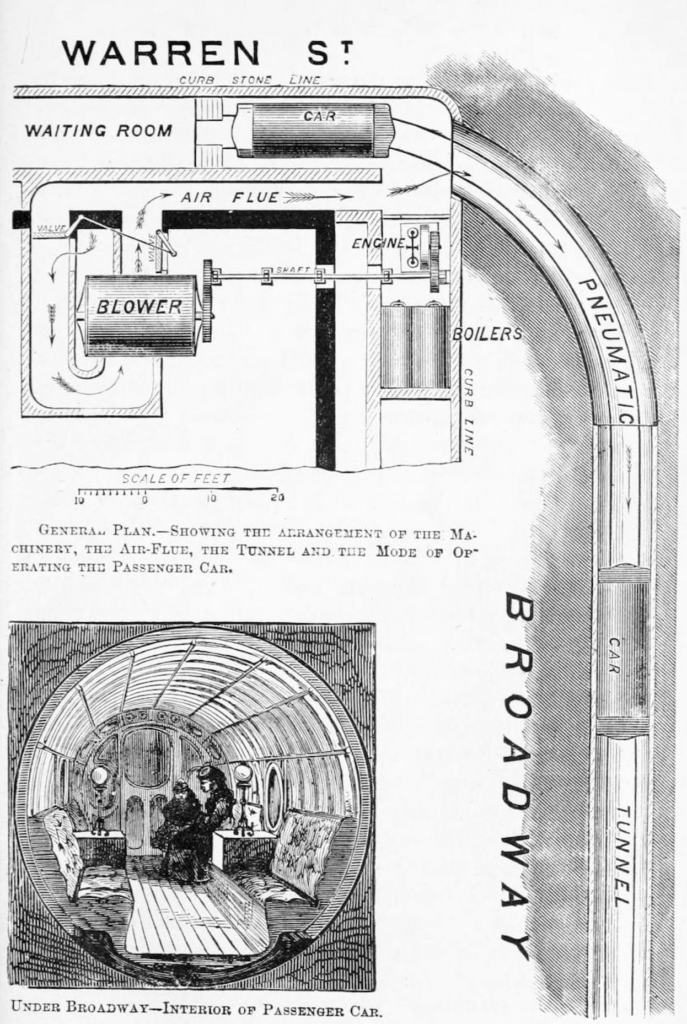

Beach notably incorporated elements from his previous inventions, along with new innovations. One of these was a circular tunnel shield with a sharpened face that could be advanced by 18 hydraulic rams. It was an improvement upon Marc Isambard Brunel’s design for the shield used to build the Thames Tunnel, which was originally a pedestrian walkway and later converted to hold trains. Beach’s hydraulic shield was popular enough that many of those that followed over the next years were simply called “Beach Shields.” Another innovation was the “Roots Patent Force Blast Blower,” which pushed and pulled the passenger car back at 10 miles per hour.

Image caption

In late February 1870, several notable figures received engraved invitations to the “Under Broadway Reception,” which would be held from 2 to 6 o’clock on February 26, 1870. Still cloaked in semi-mystery, the event would soon become the talk of the town. Those lucky enough to receive an invitation entered Devlin’s Clothing Store and descended several steps into a brightly-lit 120-foot long waiting room, complete with a fountain populated with goldfish, large paintings, mirrors, lush curtains, and a piano. Another series of steps led to the entrance of the tunnel, lit up by bronze gas lamps, the top of the tunnel emblazoned with “Pneumatic Transit, 1870.” The car was circular to fit the tube, and featured luxurious upholstered seats and oxygen gas lamps. It was an immediate sensation.

A plan showing how the 300 foot tunnel turned at a great angle and continued down Broadway. The inset shows the appointment of the passenger car. From New York and its Institutions, 1609-1871 by John Francis Richmond.

The Broadway Underground Pneumatic Railway opened to the public on March 1st, and people clamored for a ride. Although the tunnel was only 300 feet long, and didn’t qualify as any sort of proper transportation system, it was nevertheless a popular attraction, with people paying 25 cents to enter. Although Beach had sunk over $350,000 of his own money into the projects, all of the proceeds went to the Union House for the Orphans of Soldiers and Sailors. Thousands of people flocked to see the spectacle and, most significantly, to sign in support of the project.

The view down the short tunnel, looking south under Broadway. From Harper’s Weekly, March 12, 1870, Volume 14, Number 689.

Of course, Beach was already caught up in litigation, but pushed forward in an attempt to get a franchise to build and operate a longer line, perhaps as far as Central Park, as Beach excitedly told visitors. While state legislators eagerly backed a bill to allow funding for this, “Boss” Tweed had also worked to advance a plan for his competing “Viaduct Railway” and both bills appeared on the desk of Governor John T. Hoffman, who swiftly vetoed the former, and passed the latter. However, scandal soon caught up with Tweed, and the viaduct plan went nowhere.

The old tunnel, photographed c. 1913. Compare this to the view above. From Old Beach Tunnel – Report of the Public Service Commission, For the Year Ending December 31, 1912.

Although Beach continued to advocate for his pneumatic railway, enthusiasm waned, and by the time the bill was passed again in 1873, he was scrambling for investors. They didn’t materialize, and by the end of the year the economy collapsed, with the Panic of 1873 wiping out any future for the railway. Beach was forced to shut the project down, and returned to his other work, briefly renting the space out before closing it up altogether.

Views of the pneumatic tunnel and its remnants, including the tunnel shield on the lower right. On the lower left is a ticket that allowed the purchaser to take a ride. From Fifty years of rapid transit, 1864-1917 by James Blaine Walker.

The city’s first subway was quickly forgotten, and elevated lines soon sprang up across Manhattan and Brooklyn. Less than 40 years after the pneumatic subway opened its doors, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company began operating their subway line up to Harlem, with the City Hall loop just a stone’s throw away from the pneumatic tube. In 1912, workers constructing the BRT Broadway Line came across the old tunnels, which still had the hydraulic shield and passenger car in place as they had been left. The shield was saved by Beach’s son and presented to the engineering museum at Cornell University. Everything else was destroyed. A plaque was ordered in 1932 to commemorate the pneumatic railway, and reportedly placed in the BMT City Hall station, but its exact location is unknown.

Select sources

- Subway City: Riding the Trains, Reading New York by Michael Brooks

- Uptown/Downtown: A Trip Through Time on New York’s Subways by Stan Fischler

- 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York by Clifton Hood

- The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway by Doug Most

- New York Underground: The Anatomy of a City by Julia Solis