A view of Grand Central and some of the planned and constructed buildings that were to be part of the “Terminal City” complex. In 1919, the Commodore Hotel opened in the open space on the right. From New York, The Wonder City, issued by the American Art Publishing Company.

Just after the clock struck midnight on February 2nd, 1913, the new Grand Central Terminal was opened to the public. A crowd of 2,000 people had gathered outside the terminal in anticipation of the official opening. Many of them were dressed in evening wear, and had come directly from the theatre, skipping dinner in favor of the occasion, with their cabs stopping on Vanderbilt Avenue, which opened along with the terminal.

Grand Central Terminal and the Hotel Commodore, c. 1920. The structure in the foreground is the 42nd Street spur of the 3rd Avenue elevated, which closed in 1923. From Country life in a big city, published by the Williamsburgh Post Card Company.

Grand Central Terminal was a marvel of efficiency and convenience, the culmination of many years worth of planning, engineering, and construction. The New York Central paid close attention to the movement of passengers, and carefully coordinated their movements in the new terminal, which included gentle ramps to help guide riders to their trains without any encumbrance. The top level was reserved for long-distance trains like the famous 20th Century Limited, with the suburban concourse for local commuters a level below it.

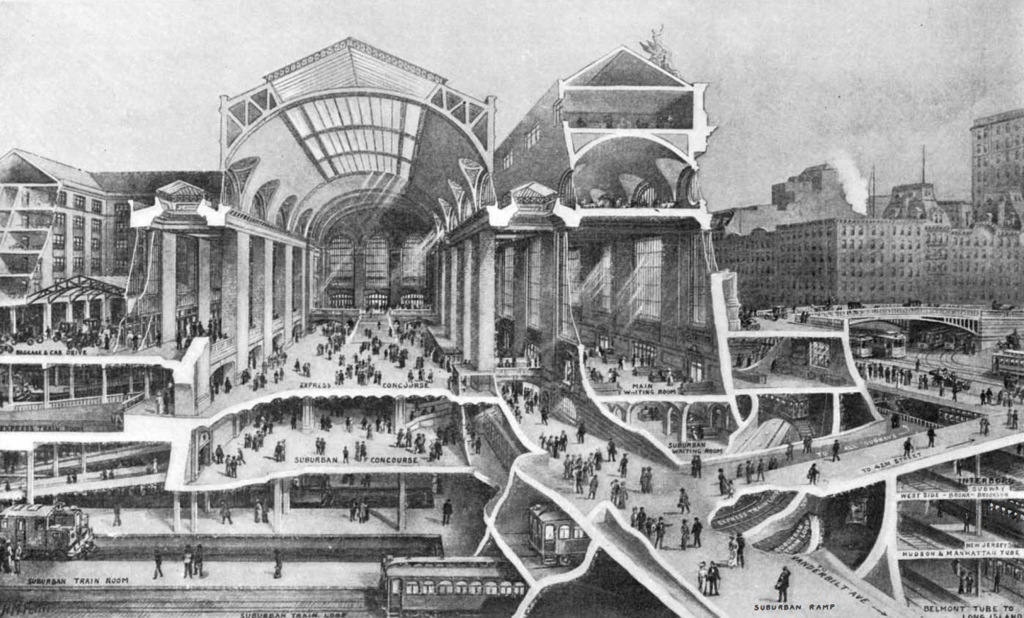

A cross-section of Grand Central Terminal as it would look when completed in 1913. It was anticipated that the terminal could handle 200 trains per hour across the two track levels. The designs changed considerably over the years, and construction continued after opening day (for example, the viaduct was not yet finished, and the huge sculpture and clock adorning the face of the terminal wouldn’t be ready for installation until 1914). From Scientific American, June 17, 1911.

As people entered the terminal, a band played “The Star Spangled Banner,” and “Auld Lang Syne.” A simple ceremony was held on the main concourse, right next to the information booth. Chief engineer George A. Harwood handed over an ornamental two-foot gilded key to terminal manager A.R. Whaley. Whaley also received the keys to the facilities, which he then gave to Miles Bronson, the new terminal manager (Whaley was taking a new position as vice president of the New York, New Haven Hartford Railroad). It was all over in less than two minutes.

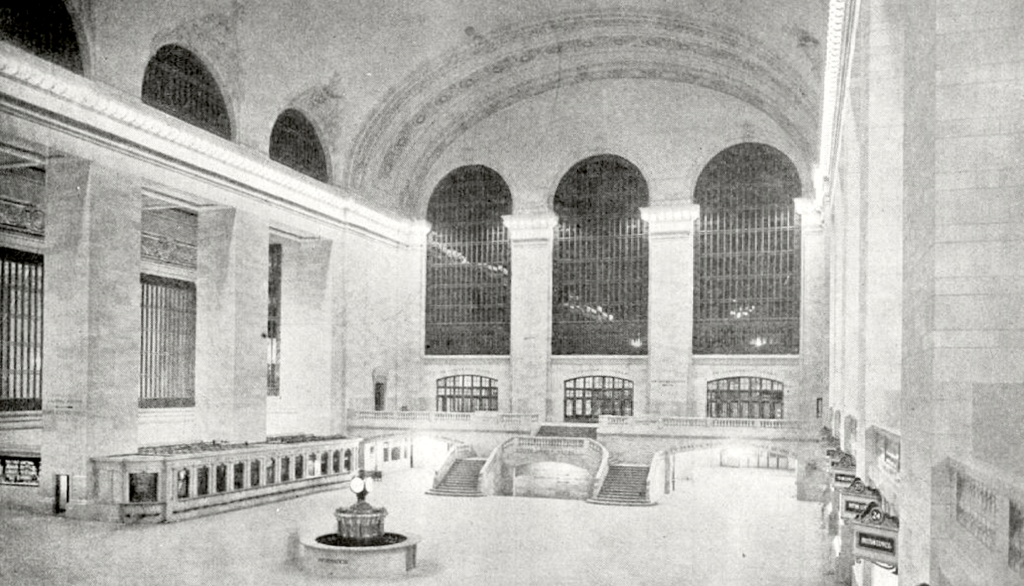

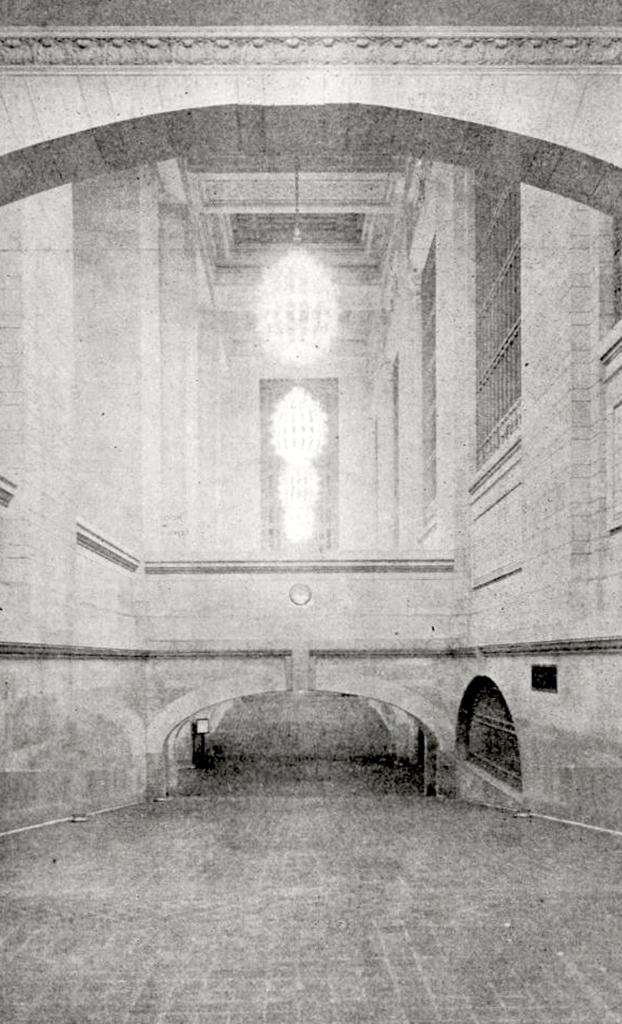

The express concourse as it looked before the terminal opened. Over the years, the gleaming marble became badly discolored by tobacco smoke, leading to a massive restoration effort in the 1990s. From Real estate record and builders’ guide, July 5, 1913.

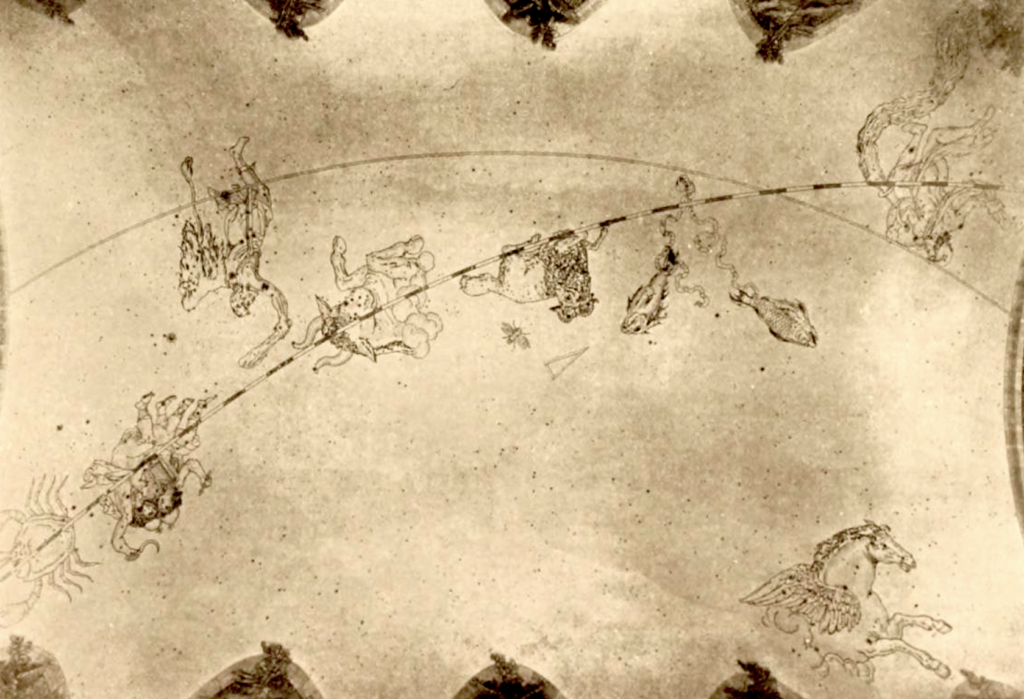

Folks eagerly explored the new space, the crown jewel of which was the massive main concourse, decorated with a magnificent celestial ceiling designed by Paul César Helleu, which includes over 2,500 gilded stars and 59 bulbs lighting the major stars (the original ceiling was heavily damaged by water and was replaced with a mural painted on panels in 1944). The terminal was bathed in light, including a series of magnificent bronze chandeliers with bare bulbs, dubbed “electroliers.” Thought was given to even the most basic objects, and the terminal was awash in acorns and oak leaves, the chosen symbols of the Vanderbilt family.

The iconic ceiling, which due to a series of mistakes wound up being painted backwards. A lot of the intricate details on the original ceiling were lost when the panels were installed. One can make out the panels from the concourse floor. From Architecture, Volume XXVII, Number 3, March 1913.

Five of the “electroliers” hang over the ramps to the suburban concourse. To the right is the express concourse, and to the left is the main waiting room. From Real estate record and builders’ guide, July 5, 1913.

Several people purchased tickets on the first train to leave the terminal, scheduled to depart at 12:25 AM; they got off at 125th Street. Other “railbirds” were content to watch from afar with glee as trains arrived and left, while others peppered railroad officials with questions about the elaborate signal system. Those who had skipped dinner could enjoy a meal at the Grand Central Restaurant (now part of the Oyster Bar), which had been in operation on February 1st, as it hosted two banquets for railroad officials and employees. Over the course of the first day, an estimated 150,000 people visited the terminal to see and admire it, and it immediately became an iconic part of the city.

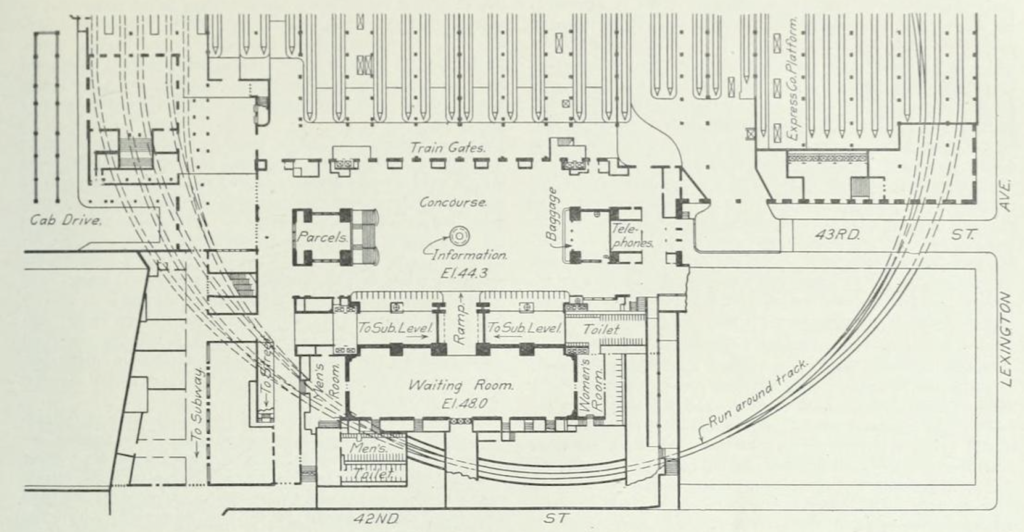

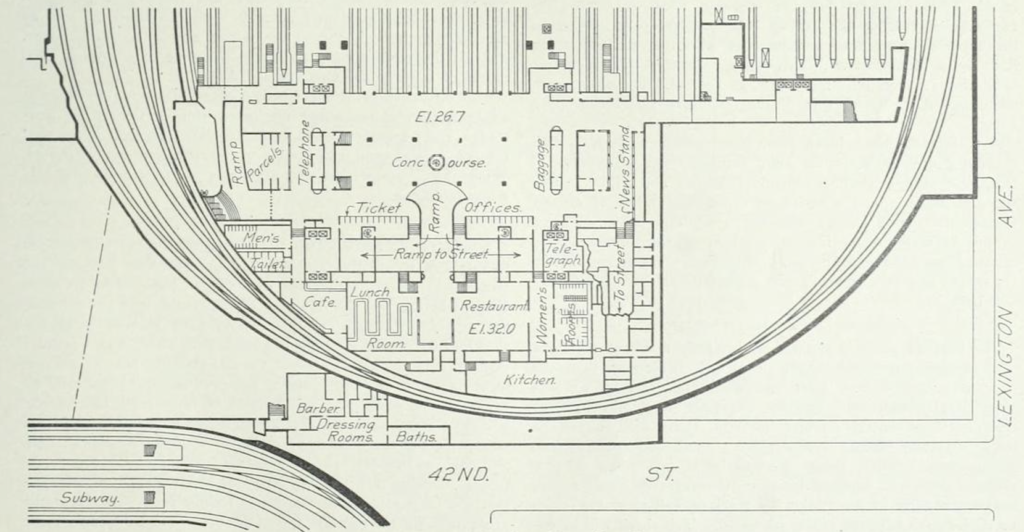

Plan of Express concourse level (above) and plan of Suburban concourse level (below), showing some notable features and how they relate to the tracks. From Railway Age Gazette, Volume 54, Number 7, February 14, 1913.

Select sources

Grand Central: Gateway to a Million Lives by John Belle

Grand Central Terminal: 100 Years of a New York Landmark by Anthony W. Robins and the New York Transit Museum

Grand Central Terminal: Railroads, Engineering, and Architecture in New York City by Kurt C. Schlichting

Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (The History of NYC Series Book 2) by Mike Wallace

Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal by Eric K. Washington

Newspaper articles

- “City’s New and Greatest Gateway Opened Today.” The Sun. February 2, 1913.

- “Grand Central Terminal to Open To-Day.” The Brooklyn Citizen. February 2, 1913.

- “New Grand Central Opens its Doors.” The New York Times. February 2, 1913.

- “Throng Visits New Terminal.” The Brooklyn Citizen. February 3, 1913.