The British took over New Netherland in 1664, and English rule passed onto the residents of Harlem, several of whom left to go home to Holland. Others took the oath of allegiance to England, and people continued to buy land in the village. In 1665, Governor Richard Nicholls issued a proclamation establishing a new government, specifying that all of the people of New York and New Harlem would be established under one Mayor, Alderman, and Sheriff. Much like the Dutch, the British recognized the considerable benefits of having an additional settlement on Manhattan.

Continued from Part 1, The Early History of Nieuw Haarlem: Manhattan’s Other Village.

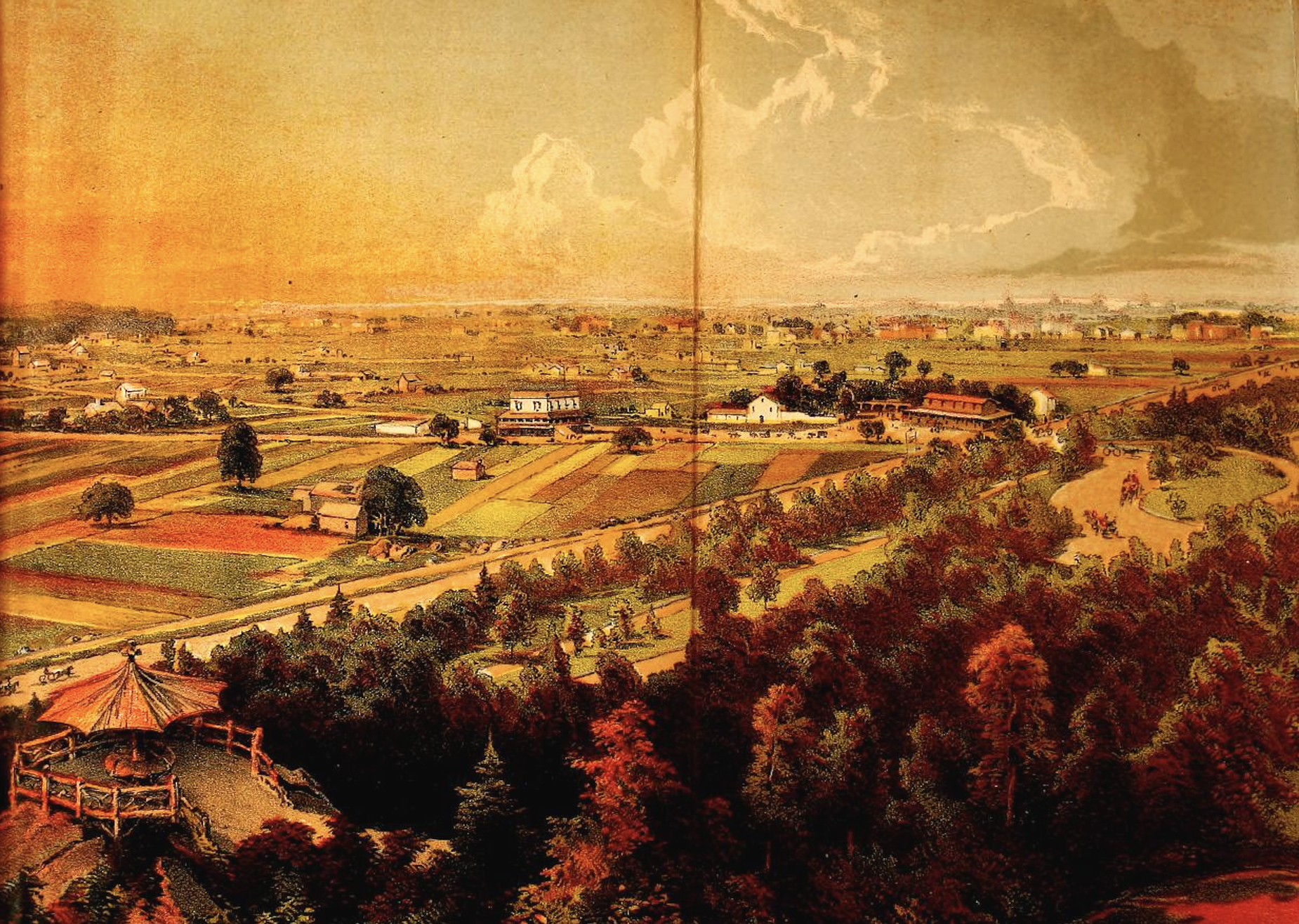

The Harlem Plains from the Central Park Blockhouse, 1869. In the foreground is 110th Street, and across the horizon is the Harlem Lane, now St. Nicholas Avenue. The Harlem Lane followed the old Wecquaesgeek trail, which later served as part of the Post Road. By the mid-19th century, it was also used as a racetrack. From D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1869.

With the village continuing to grow as new people moved to the area, residents appealed to Governor Nicholls for a new charter. Nicholls sent surveyor Jacques Cortelyou, who had drawn up the Castello Plan of New Amsterdam in 1660, to New Harlem to delineate boundaries and, most importantly, lay out space for a new commons where villagers could let their livestock out to graze. The first Harlem Patent was drafted in 1666, and included conditions that one or more boats fit for a ferry be built, that the commons extend further west into the woods, and that the town should be called by the name of Lancaster.

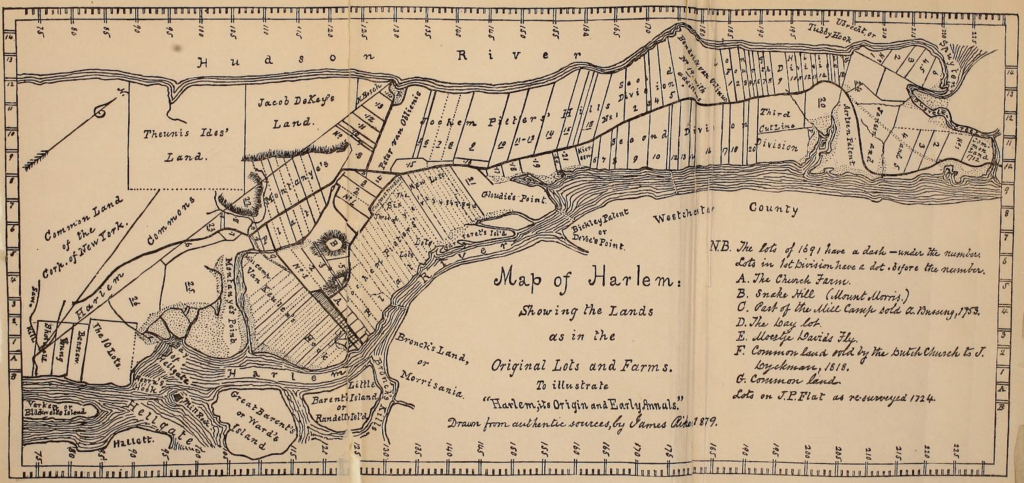

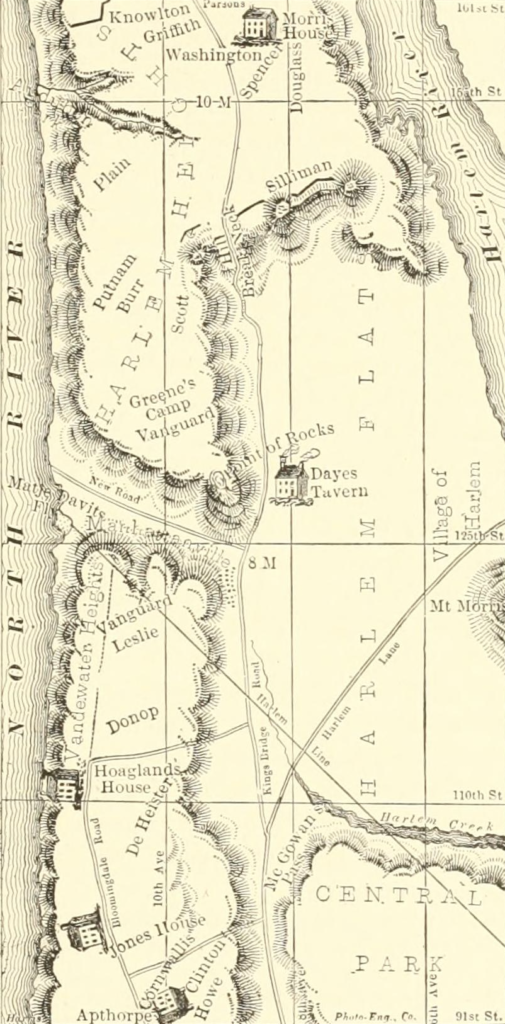

Map of Harlem, showing the lands as in the Original Lots and Farms. The Harlem Line can be seen on the left side of the map. The tract labeled A was owned by the Dutch Reformed Church, which established a cemetery in 1665 just to the north for Blacks, many of whom were slaves. The site of the Harlem African Burial Ground is near 126th Street and 1st Avenue. From Harlem (City of New York): Its Origin and Early Annals by James Riker, 1904.

This last condition was strongly opposed by residents, who were also incensed by the failure to incorporate salt meadows that farmers owned across the river. They petitioned for a new charter, which did include the meadows and allowed the village to continue to be called New Harlem. Although it was afforded the privileges of a town, it was still dependent on New York. The patents established a line, commonly called the “Harlem Line,” which drew a boundary from 74th Street at the East River to 129th Street at the Hudson River. All of the farms, roads, and natural features above that line were considered to be part of Harlem.

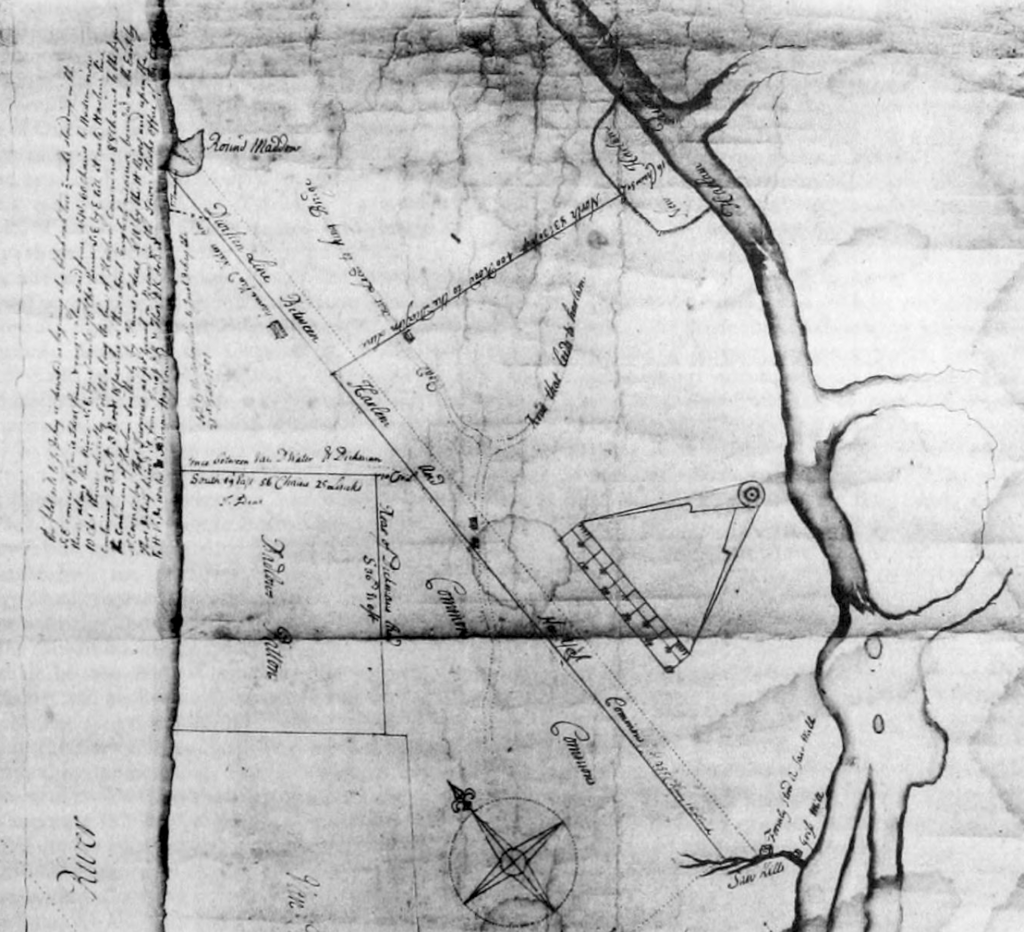

Part of a map drawn by Francis Maerschalck showing the Harlem Line, 1750. To the right the rough borders of New Harlem are shown. On the left is the Round Hollow, another name for Moertje David’s Vly. From Iconography of the City of New York, Volume 4 by I.N. Phelps Stokes, 1909.

Despite the English rule of New York, New Harlem retained a distinctly Dutch quality for many years, with villagers continuing to speak the language, cooking Dutch food, carrying on old traditions, and building Dutch-style farmhouses with the ubiquitous Dutch door to keep livestock out and let air and light in. Many residents continued to attend the Dutch Reformed church, to which one of the two main roads in the village led. There were still ample woods, meadows, marshes, and creeks that offered good hunting and fishing grounds – bears were occasionally seen, and wolves harassed livestock to such a degree that parties were organized to hunt them.

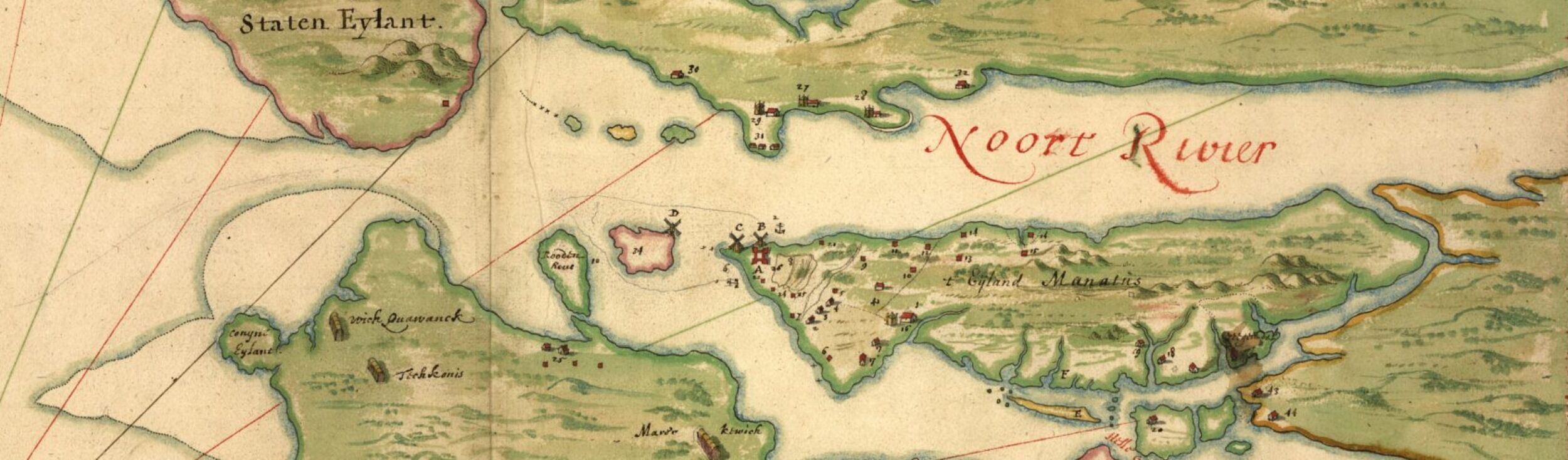

A bird’s eye view of Manhattan showing the Harlem Line. Everything above that line on Manhattan Island was considered part of Harlem. From New Harlem Past and Present: The Story of an Amazing Civic Wrong, Now at Last to be Righted by Carl Horton Pierce, 1903.

By the time of the American Revolution, the sleepy little village still remained largely independent, although it was administratively tied to the city. In 1775, the State Assembly sent a team of surveyors to verify the Harlem Line and the common lands of the City of New York, which were immediately south of the line. The northern part of the line terminated at an area known as Moertje David’s Vly (Mother David’s Valley), which is where villagers took livestock to graze, driven along a road known as the “Hollow Way,” which is modern-day 125th Street. It was on this ground and that to the south that the Battle of Harlem Heights was fought on September 16, 1776. Washington’s headquarters was at the Morris-Jumel house, and he directed the battle from a promontory known as the “Point of Rocks” near what is now St. Nicholas Park.

A sketch showing troop positions and prominent landmarks during the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16, 1776. To the right is the Harlem Plain, and to the left is the Harlem Heights (now Morningside Heights), and above it, divided by the “Hollow Way,” is Hamilton Heights. The Point of Rocks can be seen in the middle of the sketch, near the “Dayes Tavern.” At the top is the Morris House, which is now the Morris-Jumel mansion. From History of the City of New York: Its Origin, Rise, and Progress, Volume II by Martha J. Lamb, 1880.

After the Battle of Fort Washington two months later, the victorious British, now in control of York Island (one of the colonial names of Manhattan), burned nearby Benson’s Mill, and they may have also set fire to Harlem at the time. Additional structures would periodically be torched throughout the course of the war. Many residents who could afford to do so left, with some of them, like members of the Montagne family, joining the Patriot cause. Others left for safer places, as the intermittent skirmishing in the Bronx was far too close to home.

Following the war, the village struggled to recover, as loss of life, property, and fleeing residents who didn’t come back took their toll. Some establishments, notably taverns, had escaped destruction, and when approaching the city in anticipation of Evacuation Day in November 1783, George Washington and his men stayed at various taverns in upper Manhattan. Several years later Alexander Hamilton selected the area for his picturesque “Grange,” and in 1806 folks along the Hudson, on the spot of the old Moertje David’s Vly, established the village of Manhattanville, which had close ties to Harlem.

Hamilton Grange as it looked prior to 1889. That year it was moved to a new location next to St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. Hamilton moved to the property, which he dubbed “The Grange” after his grandfather’s property in Scotland, in 1802. He lived here until he was killed by Aaron Burr (who would later go on to marry Eliza Jumel, dying in the Morris-Jumel mansion) in the infamous duel. The copse of 13 trees on the right was planted by Hamilton in honor of the 13 colonies. From Thirtieth Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society to the legislature of the State of New York, 1925.

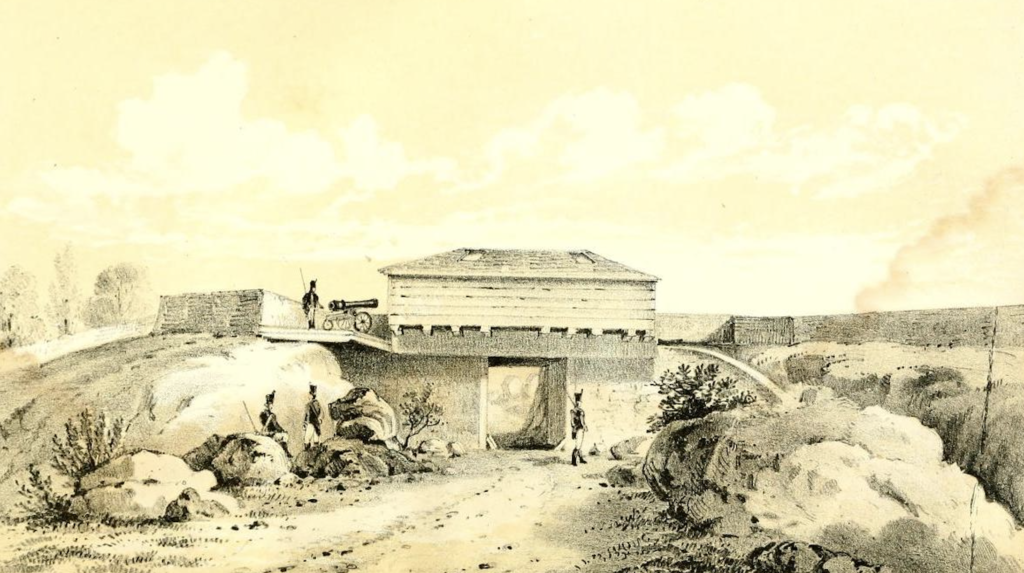

At the end of the century, Harlem still retained much of its quaint charm, with 203 residents who continued to work their farms. However, the specter of another war with Britain caused much consternation in New York. Several harbor forts, including Castle Clinton, were constructed in anticipation of an outbreak of hostilities. Following a series of British attacks in Connecticut, the city allowed for the construction of a series of fortifications protecting the East River and upper Manhattan, stretching from Hallets Point, in what is now Astoria, across the river, to McGowan’s Pass and blockhouses leading up to Harlem Heights; Blockhouse Number 1 still stands in the North Woods of Central Park, and nearby are the sites of Fort Clinton and Nutter’s Battery. Fortunately for Harlemites and New Yorkers alike, the British did not attack.

The fortified gate at McGowan’s Pass (above), and works near the pass (below), 1814. Remnants of both of these can still be seen in Central Park. In the woods to the left is Blockhouse Number 1. Both views are from D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1856.

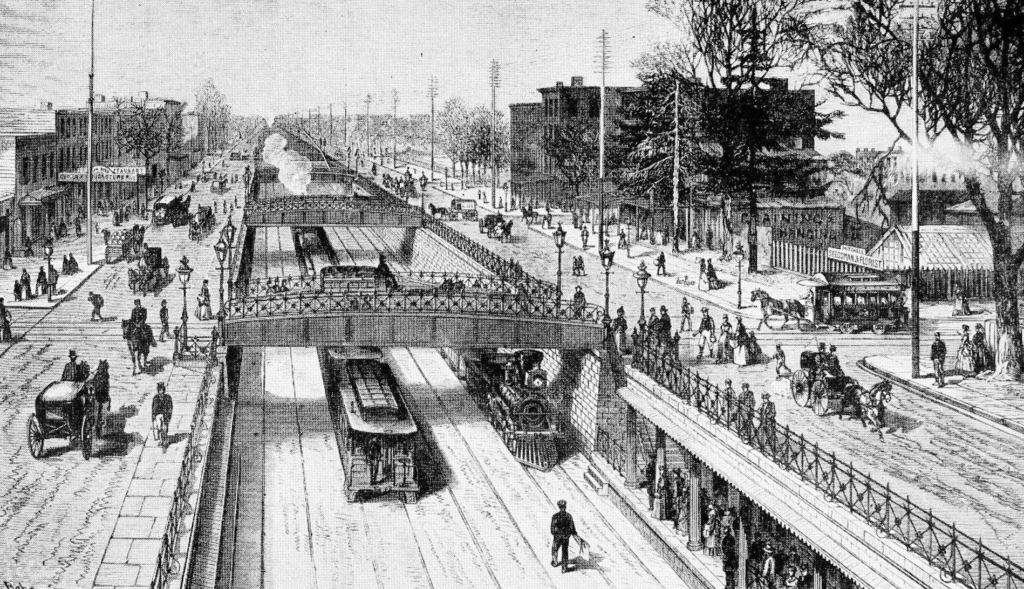

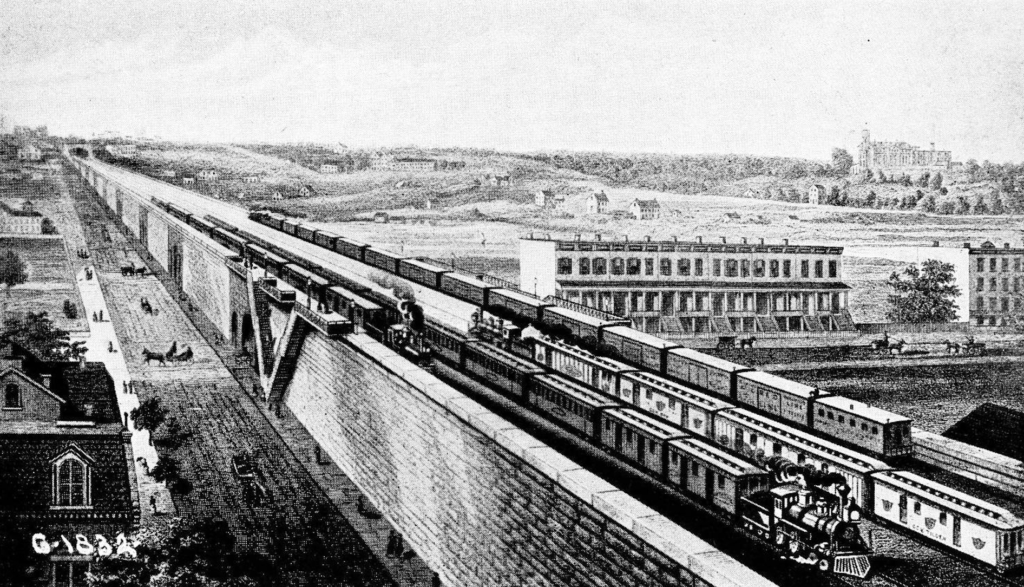

As New York grew, more folks started to buy land in the area, and the farms, surveyed by John Randel Jr., who stayed in Harlem for part of the time he was conducting his work and attended church services at the Reformed Dutch Church, would give way to the inescapable street grid. Additional ferry services began operating on both the Harlem and Hudson Rivers, and in 1837 the first trains of the New York and Harlem Railroad started to run. This provided people the opportunity to commute to the city. Streetcar lines were extended to serve Harlem and regular steamers brought folks down the Harlem and East Rivers, swiftly delivering them in lower Manhattan.

The railroad cut at 125th Street, c. 1875. The tracks descended from the viaduct at 111th Street into this open cut. When a new bridge was constructed across the Harlem River, necessitating a higher grade, the viaduct was extended, and the current station was built. The remnants of the old station are visible in the basement. From Valentine’s Manual of the City of New York, edited by Henry Collins Brown, 1923.

The New York and Harlem Railroad viaduct and station at 110th Street, 1876. This view is looking to the southwest, towards the buildings of the Mount Saint Vincent convent, located near McGowan’s Pass in Central Park. The land to the east is mostly vacant, although a few rowhouses have been built along 110th Street, making a convenient commute for anyone who needed to get to New York. From Valentine’s Manual of the City of New York, edited by Henry Collins Brown, 1923.

The opening of Central Park both offered uptown residents access to a magnificent pleasure ground and boosted real estate values. Those flatlands that weren’t always the best for farming proved to be excellent for constructing buildings, and investors began to build more economical townhouses, drawing more people to the area. The commutes became even easier as the 2nd, 3rd, and 9th Avenue elevated lines were built. By the time that New York annexed Harlem in 1873, it was rapidly on its way to becoming a rather cosmopolitan mix of ethnic groups, including Germans, Italians, Irish, Jews, along with a small but thriving Black community.

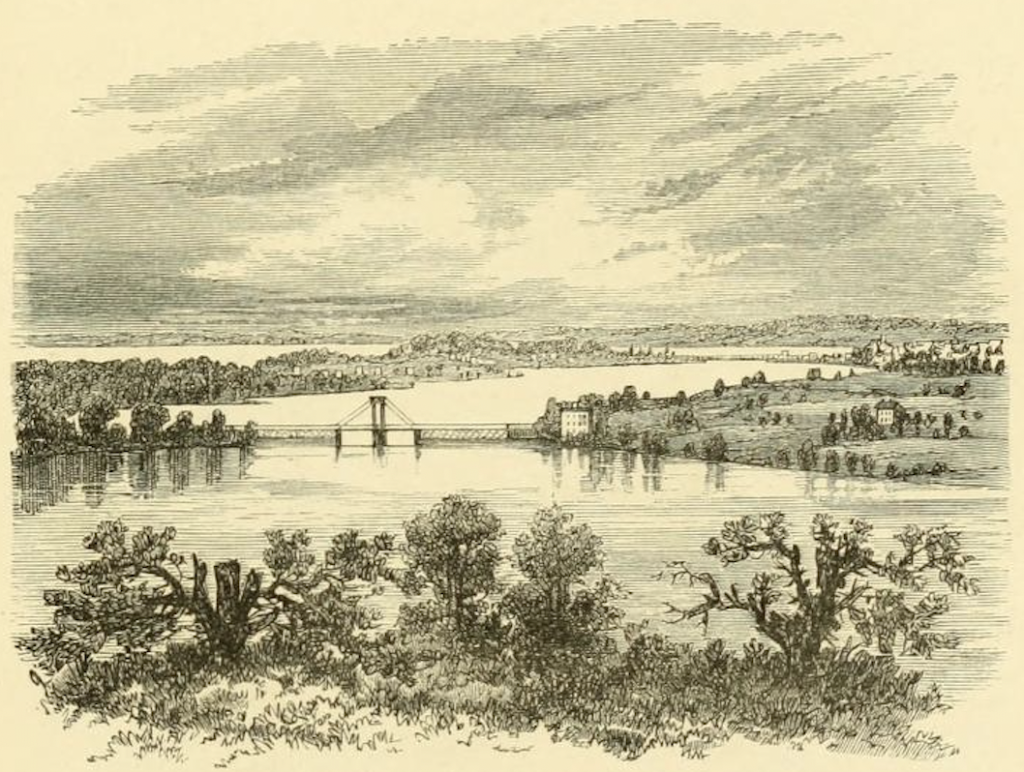

The view from the Morris Jumel mansion across the Harlem River and down to the village of Harlem, c. 1870. The bridge in the foreground is the Macombs Dam Bridge. From The Hudson, from the wilderness to the sea by Benson John Lossing.

Select sources

Before Central Park by Sara Cedar Miller

Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America by Jonathan Gill

The Encyclopedia of New York City by Kenneth T. Jackson, Lisa Keller, and Nancy Flood

Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs by Sergey Kadinsky

Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919 (The History of NYC Series Book 2) by Mike Wallace