The Tombs is one of the old New York nicknames that was so infamous in its day that it has continuously persisted for nearly 200 years. First applied to the Egyptian Revival pile of a prison that opened in 1838, the evocative name has been passed down through the years and subsequent buildings, and was still used for the Manhattan House of Detention before its demolition in 2024. Time will tell whether the nickname is used for its next iteration as well.

The Tombs next to the new Manhattan Criminal Courts Building, c. 1894. From Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, 1917-1918, edited by Henry Collins Brown.

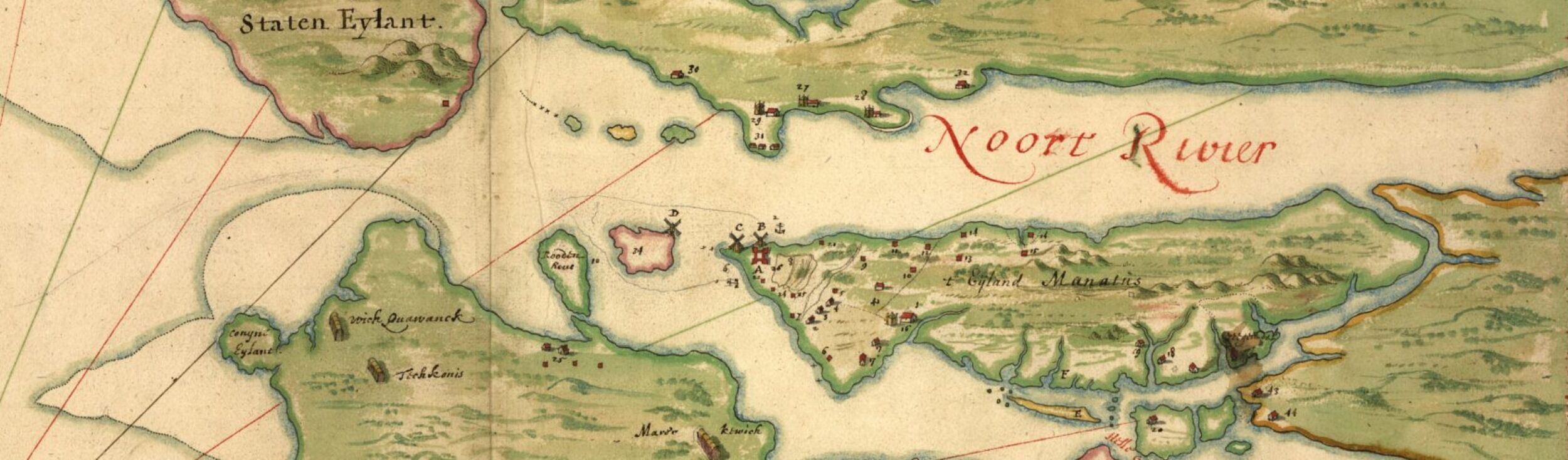

In 1835, work commenced on a grand new prison in Manhattan called the House of Detention and Justice. The location was close to the increasingly rough and tumultuous Five Points neighborhood, packed with rookeries, dives, alleys, and “fever nests.” It was built on the site of the Collect Pond, a once-idyllic spot that had been drained in the early 1800s via a canal run through the middle of the namesake street. However, this process didn’t stop the springs from running, and the land was repeatedly flooded. During the colonial era, a spit of land in the pond, sometimes called “Gibbet Island” after a particularly notorious execution, had been used for hangings.

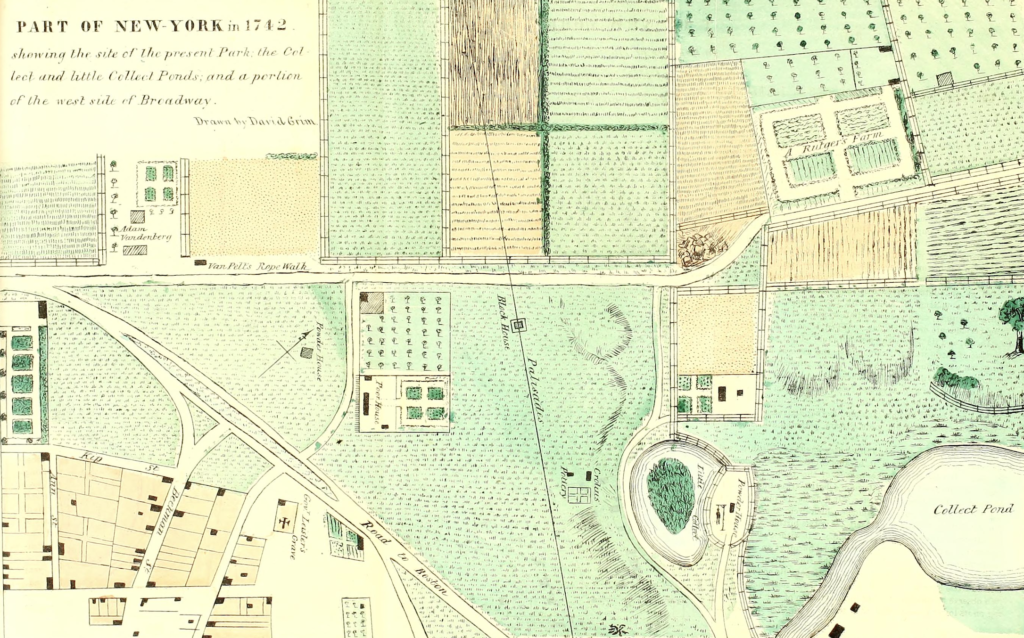

A view of the City Commons and surrounding land, including the Collect Pond, as drawn by David Grim in 1742. Next to the powder house is a gallows, recalling the individuals put to death following the Slave Insurrection of 1741. From Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, edited by D.T. Valentines, 1856.

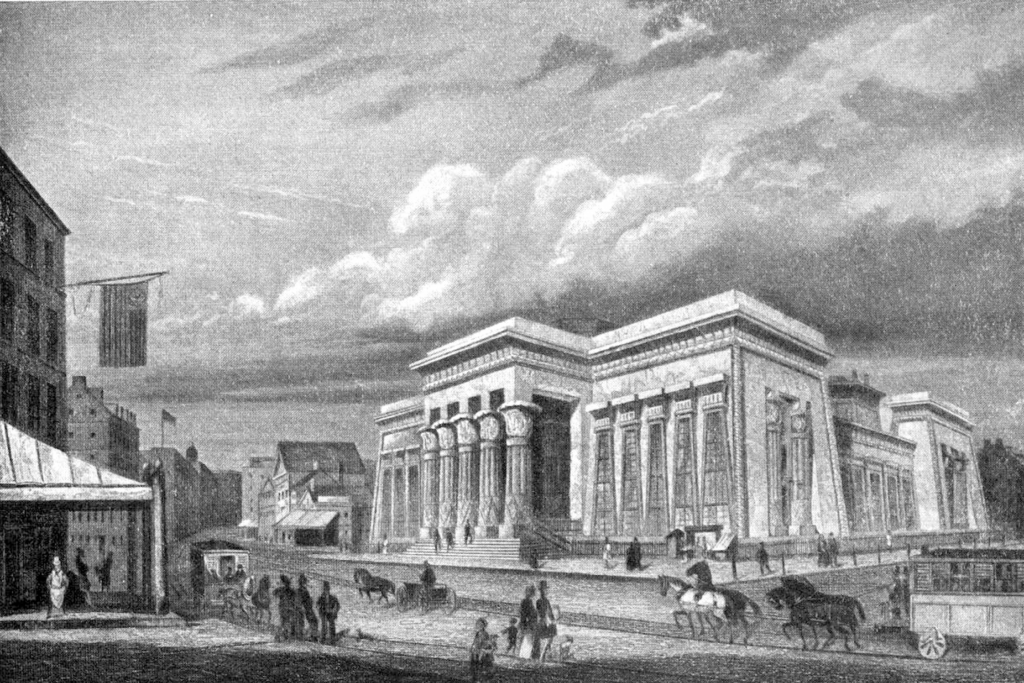

Designed by John Haviland in the Egyptian Revival architectural style, the prison was finished in 1838, clad in dark Maine granite. It was called the “Egyptian Tombs” in newspapers as early as 1840, and this was shortened to simply “The Tombs” by 1842. This is the term Charles Dickens used in his American Notes when he visited the prison, following the narrative up with a journey to the Five Points. In Herman Meville’s Bartleby, The Scrivener, the titular character is thrown into the Tombs and dies there. Mark Twain’s seminal The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day also featured a character that spent time in the Tombs.

The prison took up the whole block between Centre, Leonard, Elm (now Lafayette), and Franklin Streets. From Old New York, Yesterday and Today by Henry Collins Brown.

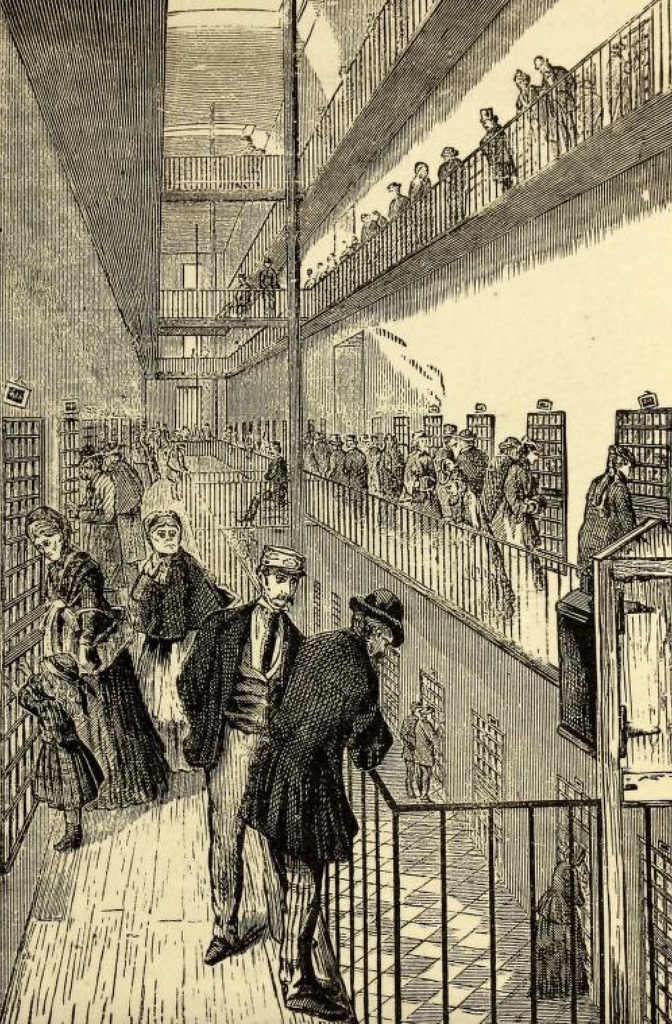

Construction was plagued by problems, and wooden piles had been used to stabilize the squat structure. However, this proved to be an immense failure, with the foundation of the heavy prison slowly sinking into the oozing ground and causing cracks in the facade and floor, letting water in. It contained four stories centering on an open corridor lit by a skylight, with prisoners sorted depending on what they were in for: the convicted prisoners, “lunatics,” and drunkards on the first floor, murderers and arsonists on the second floor, those charged with grand larceny and burglary on the third, and on the fourth were housed those charged with petit larceny and petty crimes.

The interior corridor lined with visitors. From Recollections of a New York chief of police: An official record of thirty-eight years as patrolman, detective, captain, inspector and chief of the New York Police by George W. Walling.

The main part of the prison, which housed men, had double cells that were only 6 feet by four feet. It was common for three, four, and sometimes even six to be housed together in these cells, forcing some to sleep on the slippery stone floor, and others to eat there. Prisoners were kept in their cells for up to 22 hours a day, with their only exercise being walking around the courtyard. Those of means could and did bribe officials for the privilege of a private room, bringing in outside food and liquor, having a servant, being supplied with a steady stream of cigars, allowing their wives to have a key to their cell.

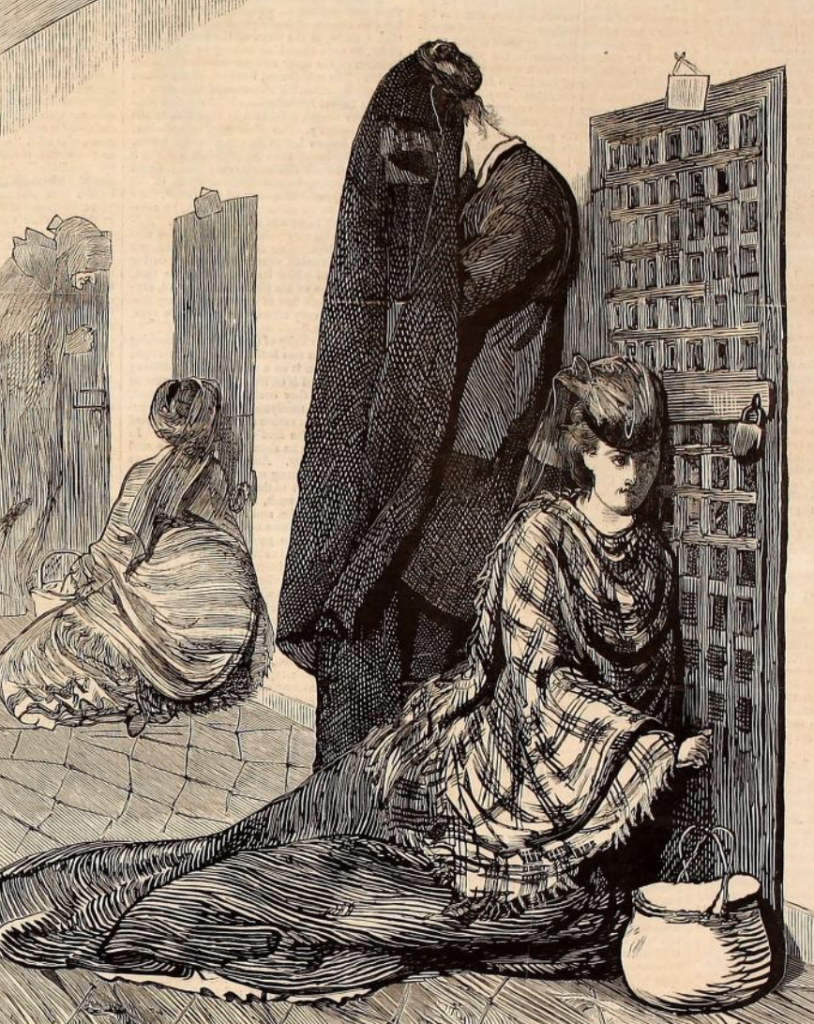

Women visiting their loved ones, 1870. For a “fee” (a convenient word for a bribe), people could bring in outside food. From Harper’s Weekly, May 7, 1870, Volume XIV, Issue 697.

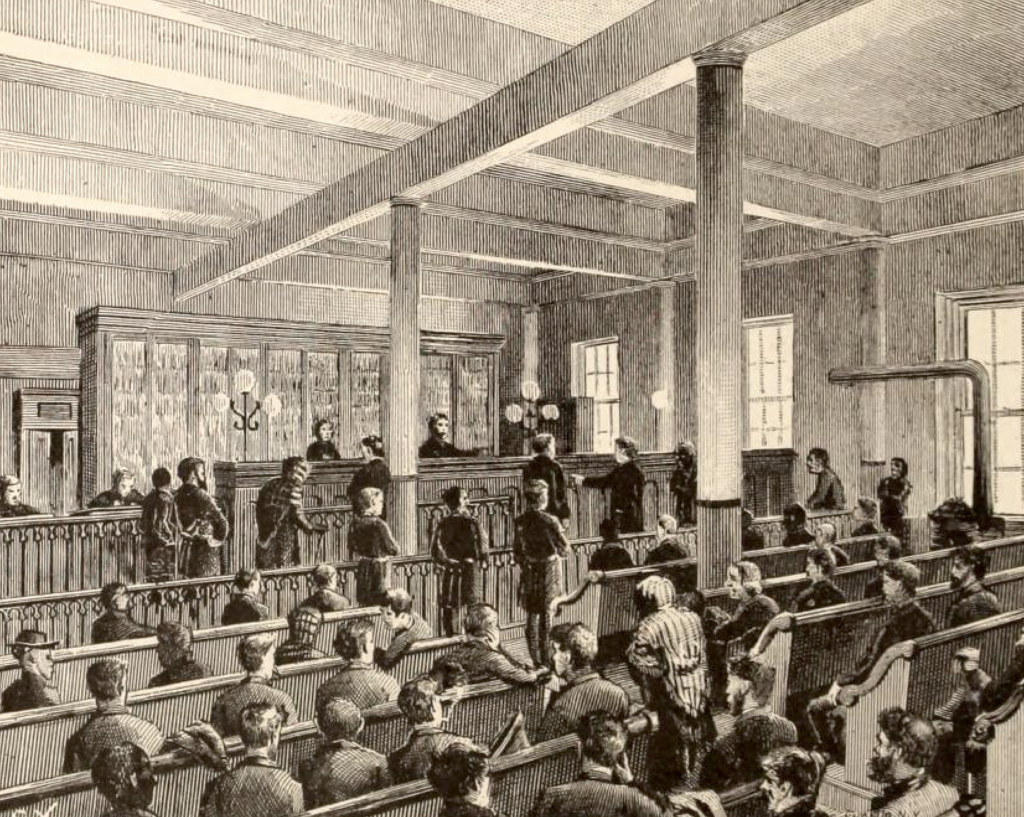

The women’s prison was separated from the men’s, had 30 cells, and was overseen by a matron. Later it was overseen by the Sisters of Charity. Many young women and even girls, some as young as ten, were held at the Tombs before being taken to one of the city’s almshouses. Another section held boys, many of whom were also quite young. When first built, the prison had a police station on the Franklin side, which was converted into a large hall for drunks, vagrants, and bums, referred to as “Bummer’s Hall.” The complex also included a police court where people were taken to be sentenced.

A scene at the Tombs police court, 1885. From Our police protectors: History of the New York police from the earliest period to the present time by Augustine E. Costello.

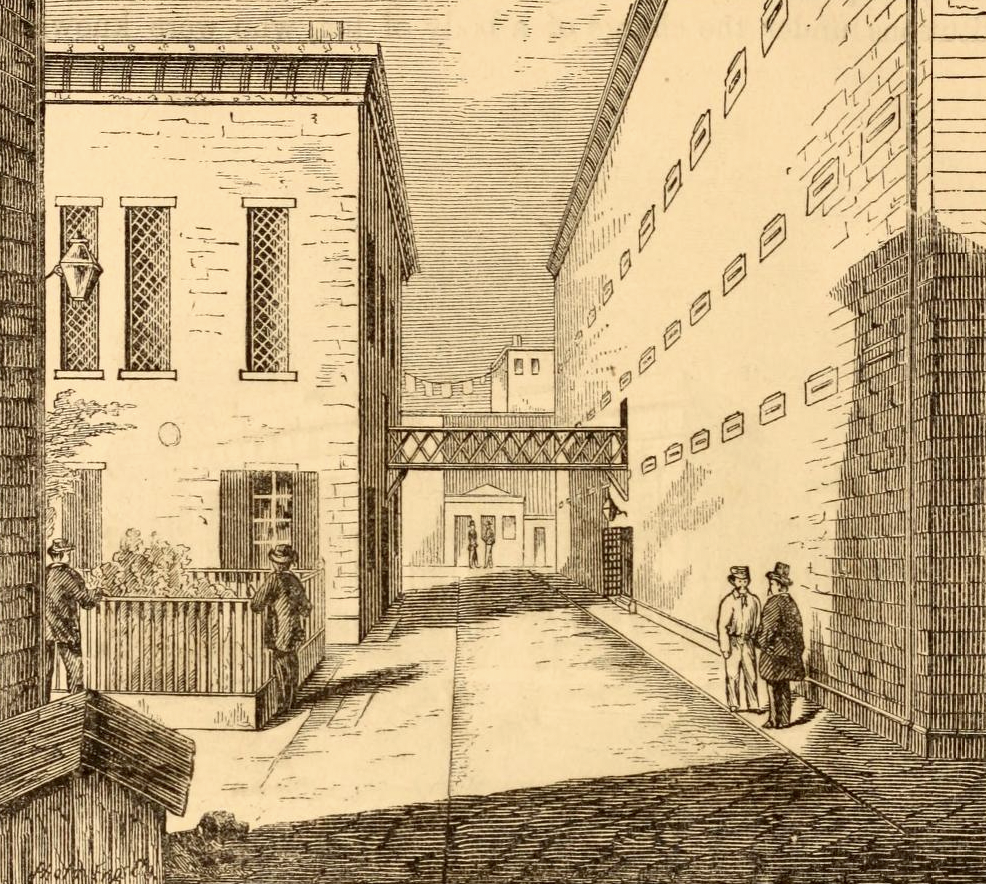

In the middle of the structure was a courtyard, which included a bridge that was dubbed the “Bridge of Sighs,” as convicted prisoners were taken over it on their way to the gallows, which was set up in the middle of the courtyard. Over the course of the prison’s history, 50 people were hanged here.

The courtyard and the Bridge of Sighs. When the Manhattan Criminal Courts Building opened in 1894 on the north side of Franklin Street, another Bridge of Sighs was built over the street, and when the old Tombs was replaced, the bridge remained. From The New York Tombs; its secrets and its mysteries. Being a history of noted criminals, with narratives of their crimes by Charles Sutton.

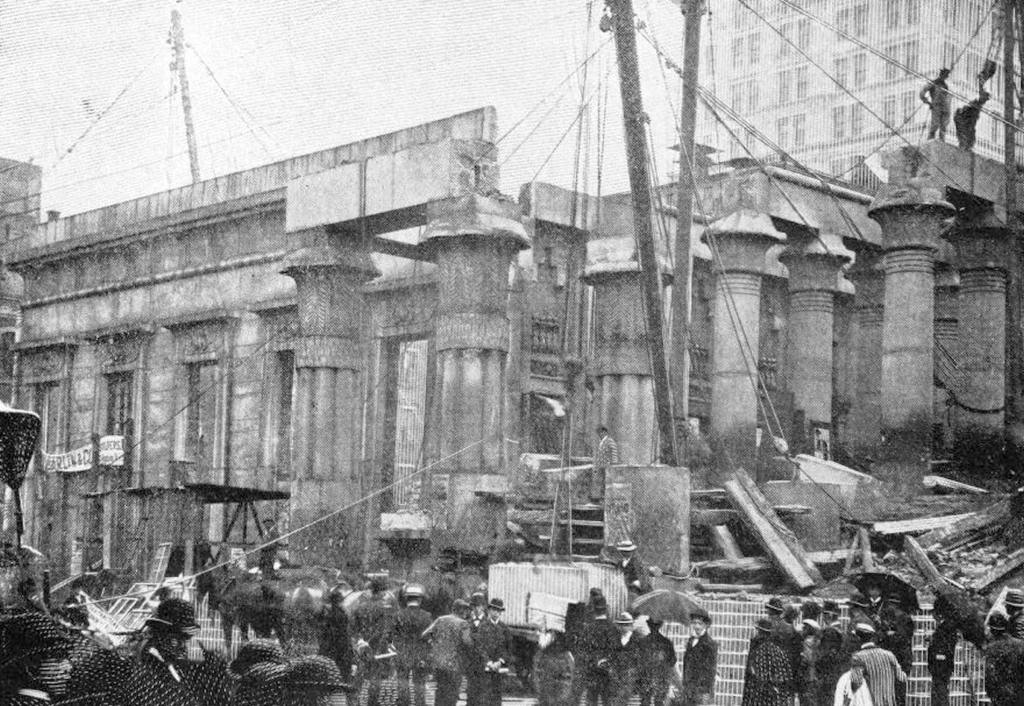

For many years there had been calls to demolish the old prison and build a new one that could adequately house the number of prisoners held within, a plan that was approved. Early preservationists argued that the facade should be saved, and there were proposals to rebuild the structure on Blackwell’s Island or Central Park, although neither happened. Demolition began on May 25th, 1897, although one last surprise came during the prison’s final hour, when contractors found four barrels in a basement storeroom that contained certificates of apprenticeship and marriage from the 1790s and 1800s, including one of the latter where the expectant bride was left stranded by her betrothed (!). Following the demolition of the old prison, a new one was built on the same site, and New Yorkers continued to call it, and its subsequent replacements, the Tombs.

Tearing down the old Tombs, 1897. Crowds gathered outside every day to watch the structure, which had become a fixture of the city, coming down bit by bit. From The American Metropolis by Frank Moss.

Select sources

The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910 by Esther Crain

A History of American Architecture: Buildings in Their Cultural and Technological by Mark Gelernter

Death in New York: History and Culture of Burials, Undertakers & Executions by K. Krombie

Prisons, Asylums, and the Public: Institutional Visiting in the Nineteenth Century by Janet Miron