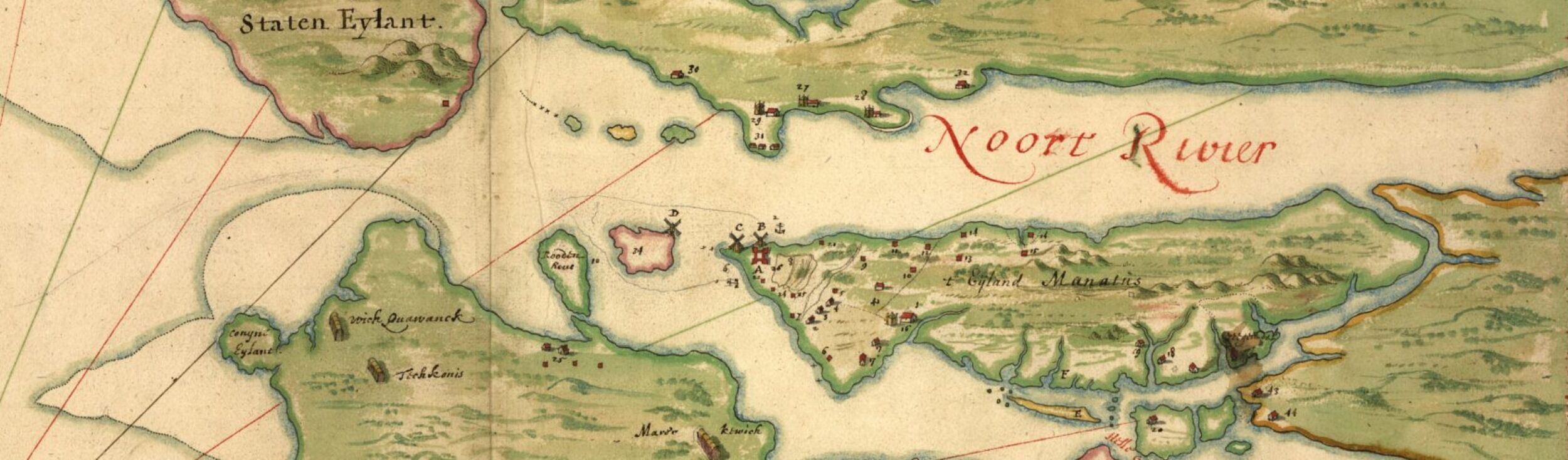

The burgeoning village of Nieuw Haarlem was situated on the banks of the Harlem River in a low-lying, marshy area with meadows, interspersed with rich soil and sandy plains, which provided excellent land for farming and growing tobacco.

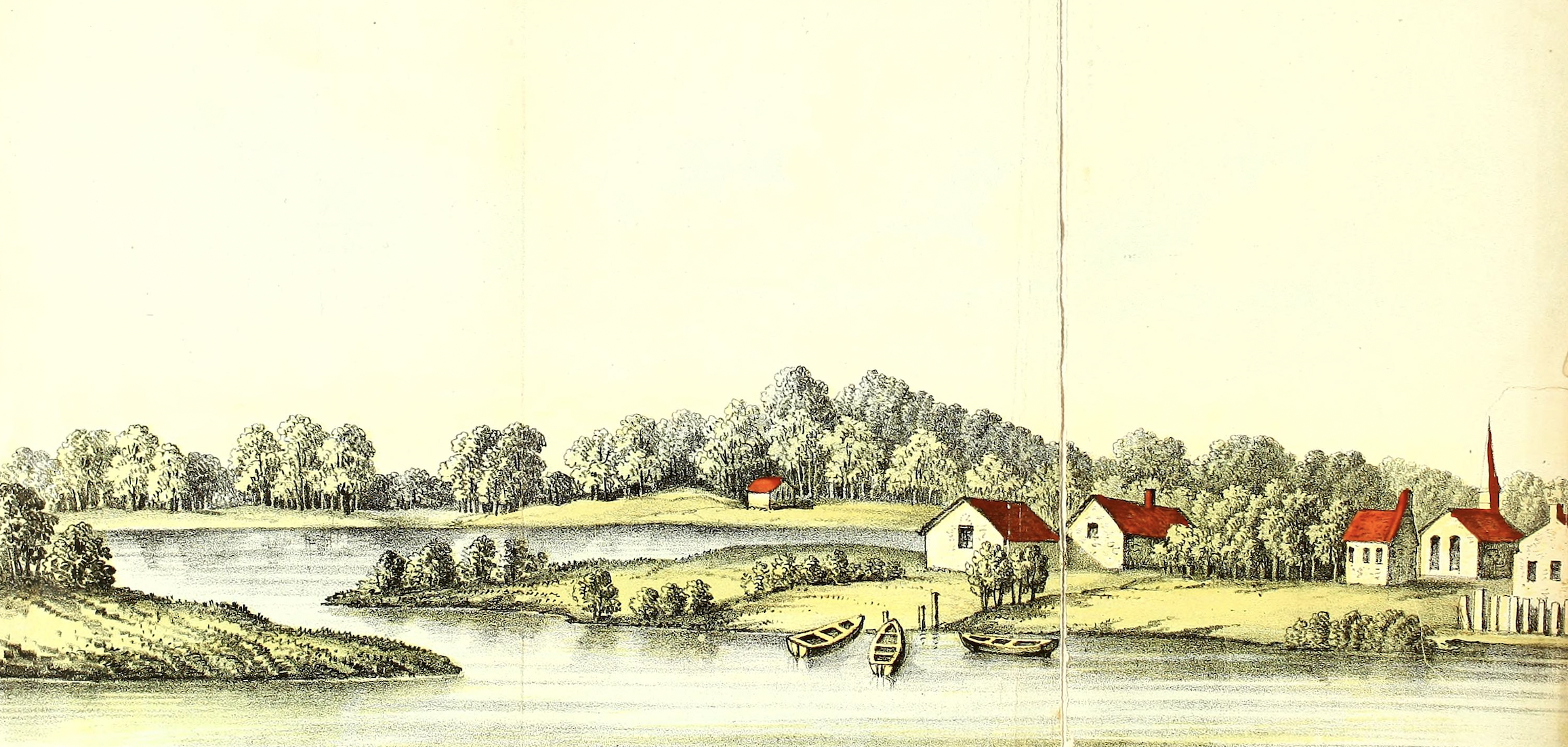

The Village of Harlem from the river, c. 1765. The Village stretched in a southwesterly course from 125th Street near 1st Avenue, which was then right on the waterfront.

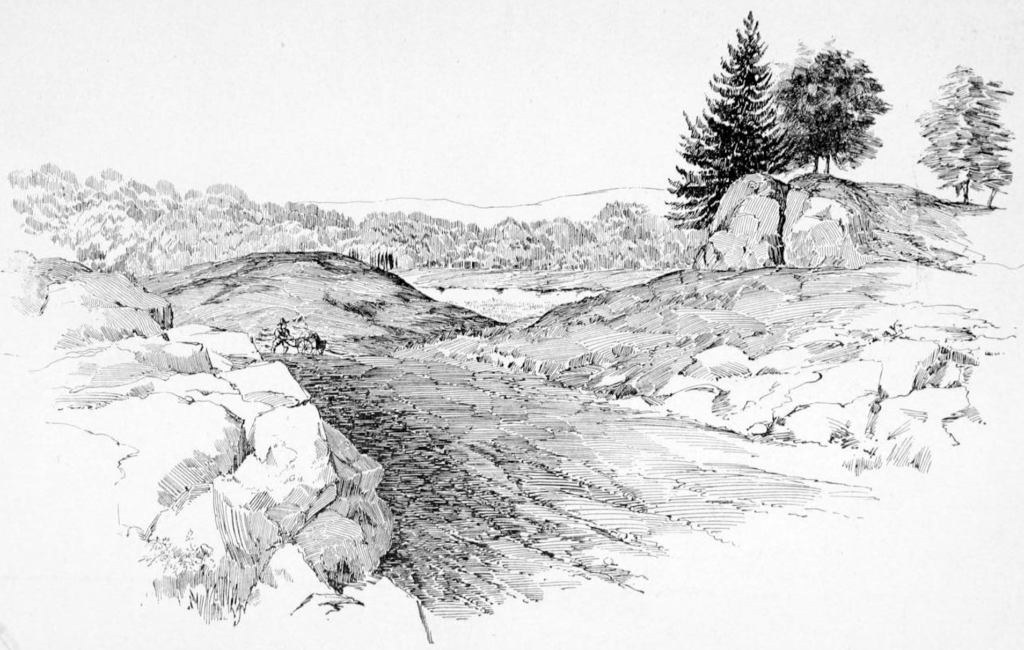

A native campsite in the area was known as Rechwanis, roughly translated to “the point between two creeks.” To the south was Konaande Kongh “the hill near to where they catch fish with nets.” A native path led from the Harlem River, with a branch to the campsite around 120th Street, to a place where the Harlem Creek could be easily forded (around 5th Avenue and 111th Street), and proceeded down through a pass in the rocks, later known as McGowan’s Pass, currently a part of northern Central Park.

An early sketch of McGowan’s Pass, in what is now Central Park. By virtue of a lighter landscaping hand, some of these rocks still remain, and you can approximate part of this view. Beyond is the Harlem Creek, which entered the East River around 106th Street. From Historic New York (Half Moon Papers), edited by Maud Wilder Goodwin, Alice Carrington Royce, and Ruth Putnam, 1897.

European settlers established bouwerij (farms) in the area and along the Great Kill (Harlem River) beginning in 1637. Johannes de la Montagne, who served as the first doctor in New Amsterdam, immigrated with his wife Rachael, their children, and his brothers in law Hendrick and Isaac de Forest. Hendrick had been granted a sizable land tract in the area, upon which tobacco was grown. After his death, Dr. Montagne managed the tract, but he would go on to swindle Hendrick’s widow out of the farm, which he somewhat ironically named Vredendal, “peaceful dale,” although Isaac would crucially maintain a sliver of his brother’s land. Jacobus van Corlaer called his land Otterspoor, “otter’s tracks,” while Jochem Pietersen Kuyter dubbed his property Zegendaal, “valley of blessings.”

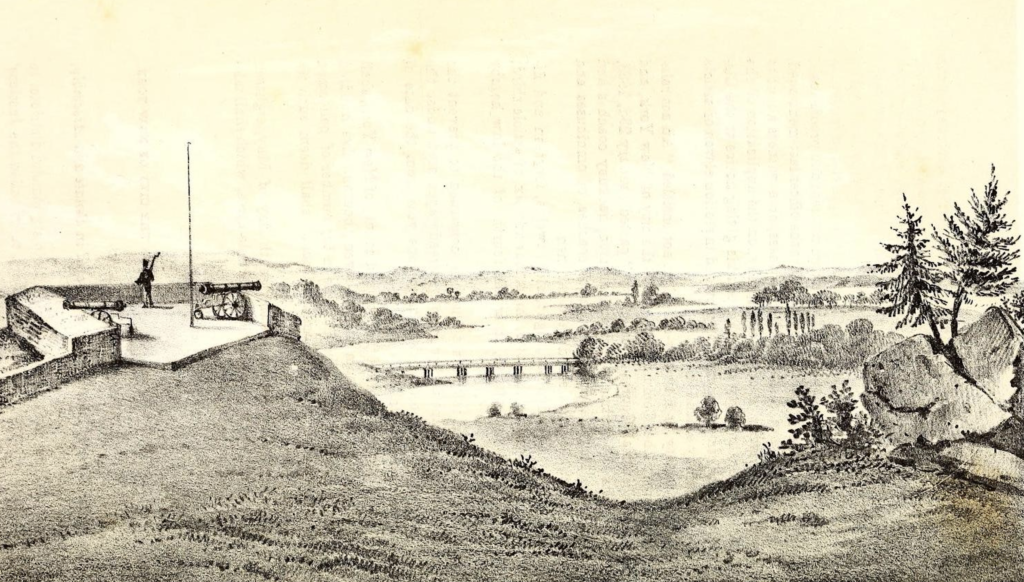

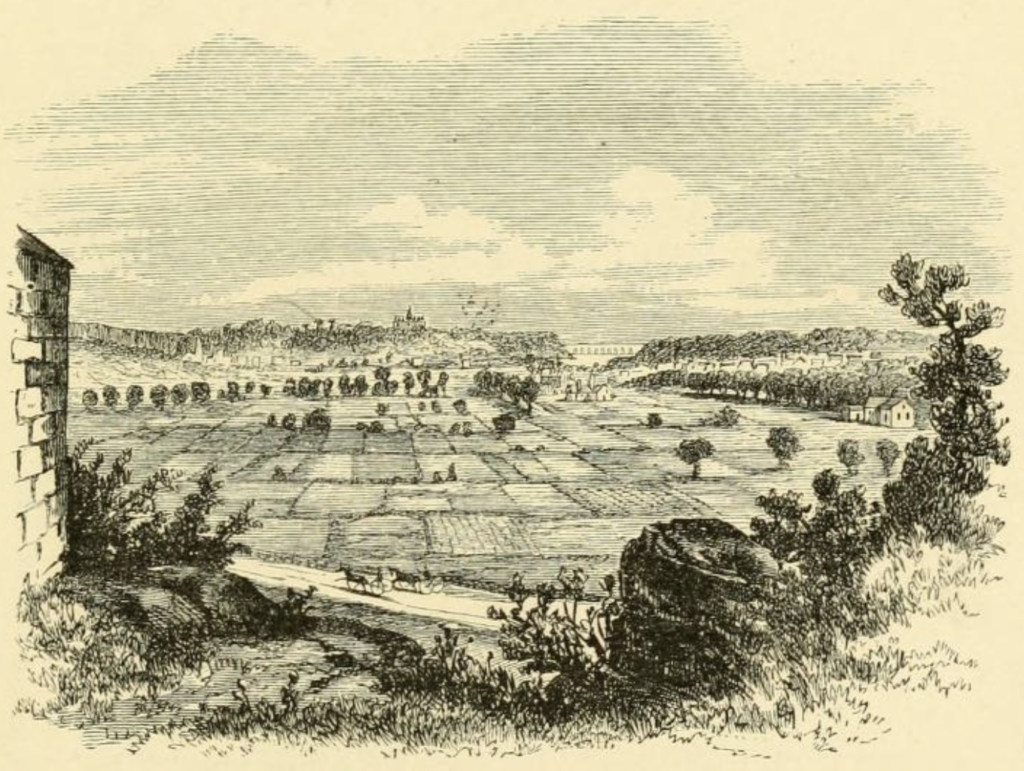

The view from Fort Clinton, part of the line of defenses built in 1812 to defend the city. Below are the Harlem Flats, also known as Montagne’s Flats. From D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1856.

The idyllic life would be short-lived as relations between the native tribes and New Amsterdam officials broke down. One of the main catalysts was the murder of wheelwright Claes Swits in 1641. Swits had leased the Otterspoor farm and set up a small workshop near 47th Street and 2nd Avenue, where he was beheaded by a young native man, who was exacting revenge for having witnessed his uncle’s murder in 1626.

Dutch West India Company Director William Kieft was set on retaliation, and although he was dissuaded from doing so by some of his advisors, including Dr. Montagne, he ordered a brutal attack, which was carried out by both Company soldiers and volunteers in February 1643 on native settlements in Pavonia (Paulus Hook) and Corlaer’s Hook. This sparked two years of full-scale warfare that spread all throughout New Netherland, with over 1,700 natives and settlers killed, including Anne Hutchinson, who had left Rhode Island after her husband died, and settled on the banks of her namesake river. By the time the war was over, and a shaky peace was established, many settlers of Harlem had been killed, and the farms lay in ruins, abandoned.

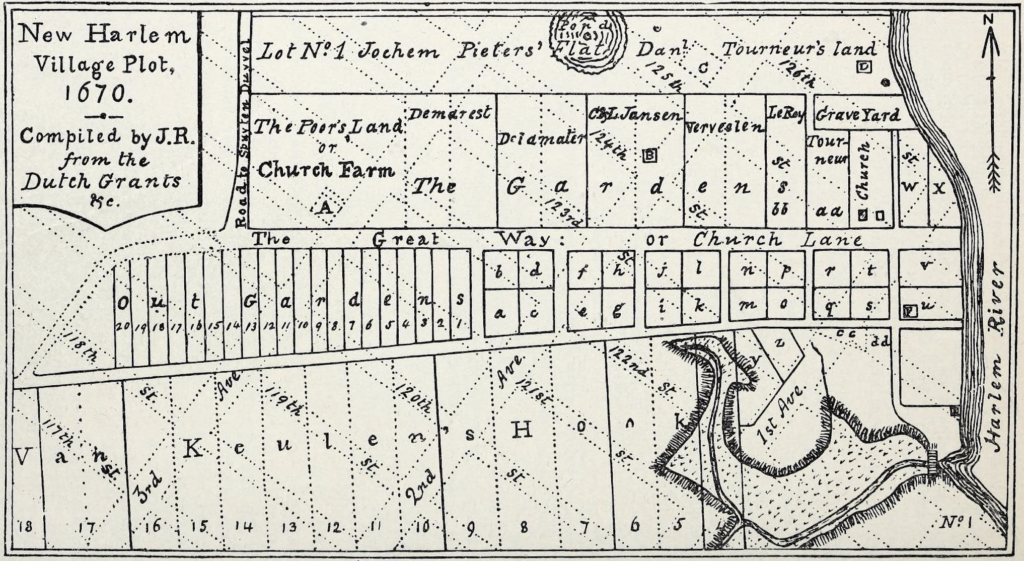

A map showing the plots of land laid, first out in August-September 1658, as they appeared in 1670. From Harlem (City of New York): Its Origin and Early Annals by James Riker, 1904.

Following Kieft’s War, and the short but highly unnerving Peach War in 1655, the Company and the Council viewed establishing a formal town outside of New Amsterdam as a highly pressing matter of security. In March 1658 the following ordinance was passed, reading:

“The Director-General and Council of New Netherland hereby give notice that for the promotion of agriculture, the security of this Island and the cattle pasturing theron, as well as for the further relief and expansion of this City Amsterdam, in New Netherland, they have resolved to form a new Village or Settlement at the end of this Island, and about the land of Jochem Peterson [Jochem Pietersen Kuyter], deceased, and those which are adjoining to it.” From The Dutch Grants, Harlem Patents and Tidal Creeks: The Law Applicable to Those Subjects Examined and Stated by John W. Pirsson, 1889.

The Company reclaimed much of the abandoned farmland, allotting grants of 18 to 24 morgens (about 36 to 48 acres) via a lottery system, with significant tax benefits for settlers. Plots for the village were drawn up by September 1658. As soon as 20 to 25 families settled in the area the ordinance provided that the village would have a minister and an inferior court of justice, and eventually a ferry, scow, and cattle and horse market. If needed, Company soldiers could come to the aid of the village, and company slaves constructed two roads, one of which followed the native path to McGowan’s Pass, and the other, named the Church Lane, which would provide frontage for some of the lots.

A sketch of Harlem Plains, showing the farms that dotted it. It seems that, as the 1658 ordinance hoped, “lovers of agriculture” indeed flourished here. From The Hudson, from the wilderness to the sea by Benson John Lossing.

Nieuw Haarlem, as the nascent village was called, was named after the city located to the west of Amsterdam. Interestingly, the area to the south and west of Nieuw Haarlem (now the Upper West Side and Morningside Heights) was called Bloemendaal, “flowering valley,” which both reflected the beauty of the land overlooking the Hudson River and recalled the picturesque district back home in The Netherlands. By 1660 the village was sizable enough to petition for the church and court, and a rather diverse group of villagers lived there, including Dutch, Germans, Swedes, Danes, French, Walloons, and free blacks. The snug community would heartily continue to thrive, even with unforeseen changes on the horizon.

Select sources

Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace

Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America by Jonathan Gill

Names of New York: Discovering the City’s Past, Present, and Future Through Its Place-Names by Joshua Jelly-Schapiro

Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs by Sergey Kadinsky

American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans by Eve LaPlante

Before Central Park by Sara Cedar Miller

Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York by Evan T. Pritchard

Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City by Eric W. Sanderson

The Island at the Center of the World by Russell Shorto

Adriaen van der Donck: A Dutch Rebel in Seventeenth-Century America by J. Van Den Hout

You Talkin’ To Me?: The Unruly History of New York English by E.J. White