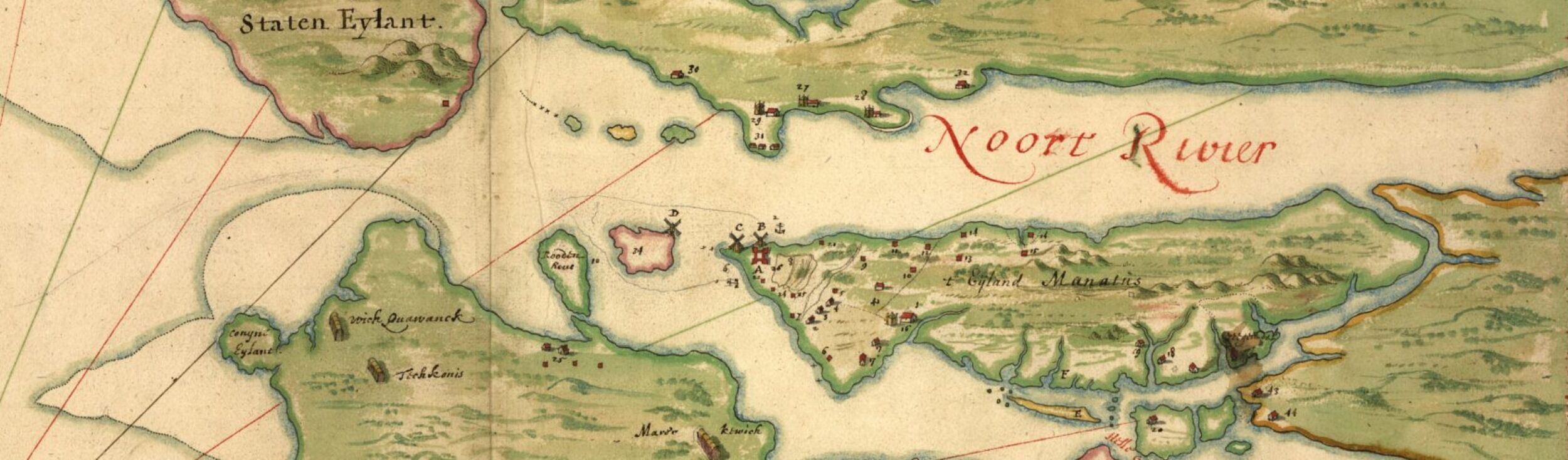

New York used to have distinct traditions for both New Year’s Day and New Year’s Eve, with the major celebration occurring on the former. In its importance New Year’s Day eclipsed that of Christmas for many years.

New Year’s Day in Dutch New Amsterdam. From Harper’s Weekly, January 4th, 1868.

In New Amsterdam, New Year’s Day was marked by people paying visits to each other. Even Dutch West India Company Director-General Peter Stuyvesant received visits, and according to one account made sure to kiss all of the ladies who came to see him. In the morning, men could go hunting for turkeys in Beekman’s Swamp, and young folks might go ice skating on the Kolch Hoek (Collect Pond), while women continued with the preparation of koekjes (cookies) and ollykoeks (a deep fried cake covered in sugar, similar to a donut), given out to visitors who came calling.

The old Dutch houses were decorated with silk and bunting, and folks exchanged small gifts with friends and family. Beer, punch, wine, and liquor flowed freely, with groups of men parading around the city and engaging in celebratory shooting. This practice had become so widespread by 1655 that it was banned in an ordinance, which was ignored to the degree that it was amended every couple of years as a reminder.

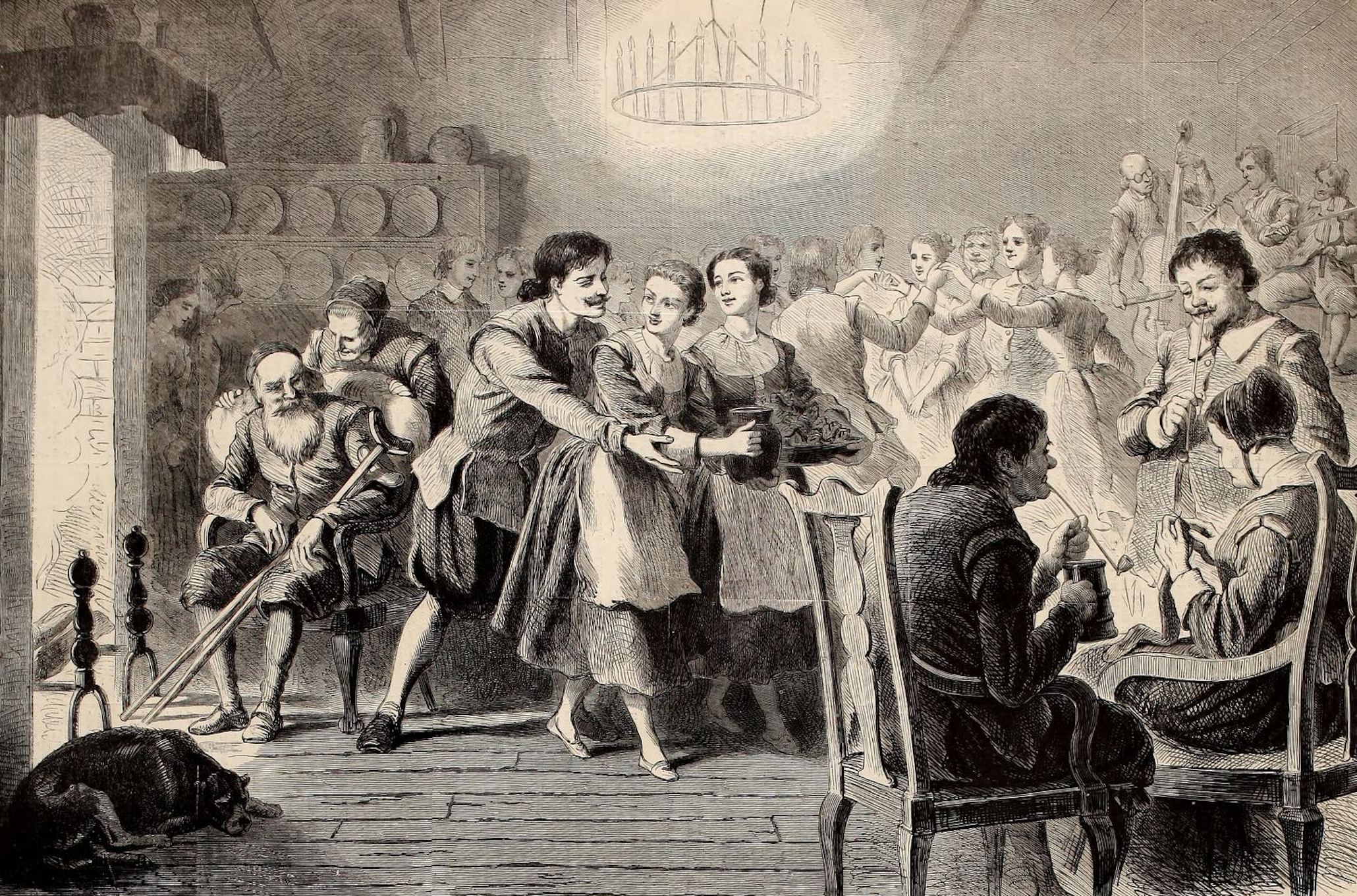

New Year’s Calling in New Amsterdam and in the 1880s. From Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, 1924.

Hosting friends and family remained a treasured tradition in New York City. On New Year’s Day 1790, when New York was still the capital of the United States, government officials visited with President George Washington for two hours, which would become an annual occurrence. That night, First Lady Martha Washington, who relished entertaining dignitaries at the Osgood (Franklin) House on Cherry Street, held a grand New Year’s reception. Dressed in a satin and velvet gown, Martha surrounded herself with prominent New Yorkers, engaging in lively conversation as servants (some of whom were slaves) offered tea, coffee, and plum cake.

The Presidential Mansion, the Osgood-Franklin House, which stood on Cherry Street and Pearl Street. From Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, 1916-1917 (New Edition, Number 2), Edited by Henry Collins Brown.

The practice of calling continued well into the 19th century, with New York City mayors opening City Hall up to callers every New Year’s Day. By the 1830s, calling had become an elaborate ritual for the well-to-do, the people who would eventually be seen as part of New York “society.” Men would call at houses, with the women greeting them in their parlors and inviting them to enjoy a bite to eat and a drink. In fact, eggnog, spiked with rum and served piping hot, was considered to be a New Year’s beverage instead of a Christmas one.

Calling in the time of the Old Knickerbockers, 1868. From Harper’s Weekly, January 4th, 1868.

It was not unheard of for men to visit 70 or 80 homes on New Year’s Day, with the first visits starting early in the morning and going late into the night. One man claimed to have made between 250 and 300 visits on a single day! Eventually, the visits transitioned to leaving calling cards, with society ladies competing to see who could gather the most. In the years following the Civil War, the tradition gradually faded as Christmas became the focal point of the season, and society folks elected to host New Year’s Day brunches or dinners at restaurants like Delmonico’s and Sherry’s, or to leave the city altogether.

Delmonico’s when it stood on 5th Avenue and 44th Street, c. 1900. From The New metropolis: Memorable events of three centuries, 1600-1900, edited by E. Idell Zeisloft.

New Year’s Eve, on the other hand, had long been a night of mischief and merriment for people of the lower classes, who gleefully took up any opportunity to mock pretensions of the moneyed set. It was common for groups, the spiritual successors to the New Amsterdam shooters, to parade through the streets on celebratory occasions, often referred to as “Fantasticals.” Others were dubbed “Calithumpians,” and strode through the streets imbibing heavily, banging pots and pans, blowing on trumpets, and playing practical jokes. However, these jovial marches, also seen on Christmas, could sometimes become confrontational, destroying property and threatening lives.

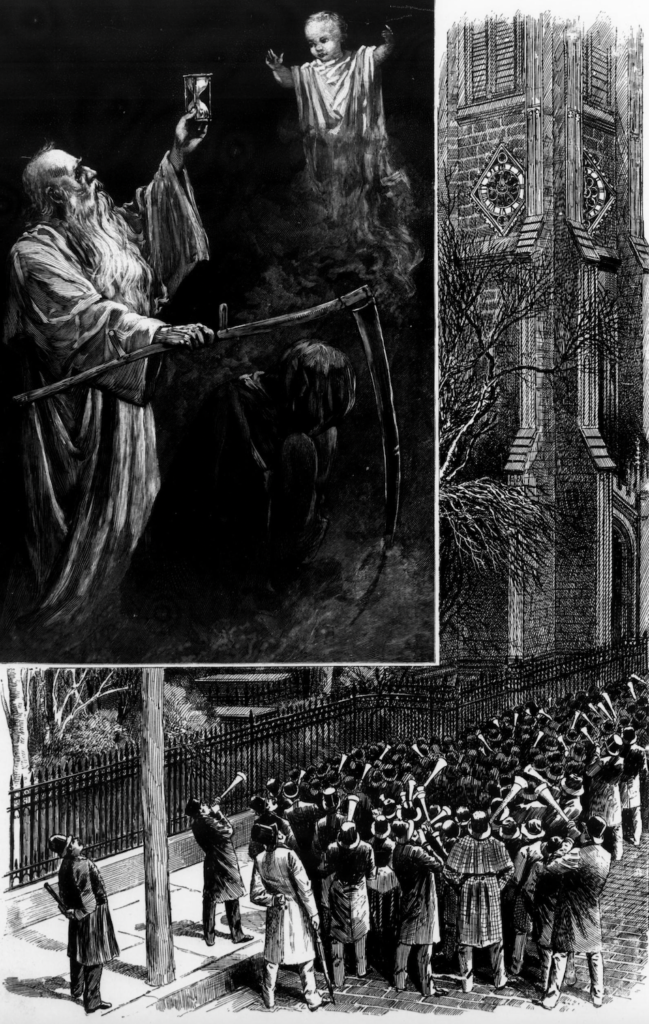

For other New Yorkers, who perhaps wanted a calmer time (although this was of course never guaranteed), it was customary to go to a church and hear the bells tolling at midnight. In lower Manhattan, the epicenter of this was of course Trinity Church, with thousands of revelers turning up to mark the passage of time. In 1897, folks in the cities of New York and Brooklyn gathered before their churches and as the bells rang out those in attendance sang Auld Lang Syne to celebrate the dawning of Greater New York. This would quickly become an annual tradition, carried on up to our present day New Year’s Eve celebrations.

Folks celebrating the advent of the New Year at Trinity Church, with an inset showing Father Time. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, January 4th, 1890.

Another common occurrence was for fireworks to be launched off of notable buildings and in public areas like parks and squares. The former Longacre Square, a prominent carriage district, was undergoing a major transformation in 1904 after the New York Times building, which still stands on 42nd Street between 7th Avenue and Broadway, opened, giving its name to the square. That year, fireworks were lit on the top of the building, attracting thousands of revelers, who also patronized the local hotels, restaurants, and clubs. It was not until December 31st, 1907 that the first ball was dropped from the top of the building, a genius marketing move inspired by the time ball erected atop the old Western Union Building in lower Manhattan, which descended each day at noon to signal the lunch hour to workers. This humble time ball has turned into one of the most recognizable symbols of New Year’s Eve celebrations around the world.